| Perhaps the most famous

power station in all England is Bankside,

now converted to become the fabulous Tate

Modern gallery. All Hallows has the same

gritty quasi-industrial quality, a

soundness and symmetry about the way

those red bricks build to their big-boned

roof, with bold angles and geometric

juxtapositions. It might be a small

cathedral, almost. It is no coincidence

that both Gilbert Scott and Cautley were

medievalists at heart. The

parish of All Hallows is one of the

poorest in East Anglia. It is one of just

four places in Suffolk designated as a

Social Priority Area by the European

Community Social Fund. But almost the

very first thing that Rick Tobin, the

current Vicar, says to me when I meet him

at the church is that "It's a lovely

parish. Such a lovely parish." Here

we are in the heart of the low-rise 1920s

Gainsborough Estate. My house is barely

half a mile from All Hallows, but the

difference between where I live in the

leafy avenues around Holywells Park and

here is jaw-dropping. These are not

streets that I would want to walk alone

at night. But Rick Tobin does just that,

and is known and loved by the people of

the estate, young and old alike. He is a

saintly, white-haired man, and somehow it

does not surprise me when he tells me of

walking through apparently

confrontational groups of hooded

teenagers, who break out into smiles and

shout "Hello, Vicar!" On one

occasion, the church suffered from a

spate of stone-throwing, with many

windows broken, especially along the

secluded north side. After he had pleaded

for it to stop, several burly, tattooed,

shaven-headed older men approached Rick.

"Don't worry Vicar, we'll find out

who's doing it and deal with it",

they told him. The stone-throwing stopped

shortly afterwards, and has never

recurred.

The great pearl beyond price

which the parish of All Hallows has

retained, but which so many urban

parishes have lost, is that there are

still generations of the same family

living on the estate who have used All

Hallows for their baptisms, marriages and

funerals. It has become a touchstone for

them and their families, and they feel a

sense of ownership of the building.

Gainsborough ward has one of the lowest

levels of higher education qualifications

of anywhere in England, but there is no

doubt that in such a low income,

generally poorly educated and

predominantly white area, the local

parish Church is still valued and treated

with respect by ordinary people in a way

that is fast vanishing elsewhere, despite

the fact that many of those people may

rarely enter it. This is a happy

circumstance for a church building of any

kind, which needs to feel the life of the

community around it. It is also, of

course, a deep irony.

I think that All Hallows is

one of the most significant 1930s

buildings in Suffolk. There are a few

which are more important, most notably,

perhaps, the Royal Hospital School at

Holbrook, and perhaps the Gaumont (now

Regent) Theatre in Ipswich. But All

Hallows is all of a piece, and its

contents still largely in their original

integrity, making this the finest

complete document of the Art Deco

movement in Suffolk. The cruciform

building has an interesting shape, which

suggests surprises inside. This

impression is rewarded as you step

through the doors. This is no mere hall.

Instead, there is a lovely interior with

a devotional atmosphere. The dimness

inside is pierced by high windows,

amplifying the sense of the numinous.

Cautley intended the people to use the

double entrance either side of the west

end, which opens onto a large space where

the two streets divide. This is now a

garden of remembrance. You can also enter

by way of a sheltered porch on the north

side of the building, into the north transept,

which was at one time designated the

'Boys Brigade' chapel, but has been

reordered to provide a space for young

children to be together during the

services. The fact that this places them

closer to the nave altar

than the rest of the congregation tells

you something about the sacramental

priorities of this worshipping community.

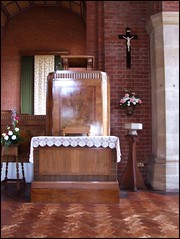

There are two altars.

The nave altar is set in the crossing,

and is the only modern intrusion into the

space. It has been designed to fit in

perfectly, although when the space is

empty you sense Cautley's intention to

create a pivotal area of Cathedral-like

intensity. Behind are the marvellous

matching Art Deco pulpit

and lectern,

like bakelite radios waiting for their

dials to be fitted. Everything is inlaid

walnut veneer, original features

completely in keeping with the building.

Beyond these are Cautley's choir stalls,

still in use for their original purpose.

The high altar is a shrine, beautiful in

its simplicity. A narrow hanging offsets

an exploding steel cross set on the altar

itself. There is no frontal, just more of

the walnut veneer familiar from the

crossing.

The south transept opposite

the entrance is perhaps the most

beautiful part of the church. It is the

Lady Chapel, curtained off from the

crossing, and the only part not entirely

Cautley's work; it was refurnished in

1951. Here, in functional brick with

narrow lancet windows, so that there is

the impression of being in an underground

crypt, there is a beautiful devotional

atmosphere. The sanctuary

echoes the medieval integrity of the

churches Cautley knew so well, with a piscina

and aumbry

picked out in brick.

To the west of the church,

the nave is the only one in Suffolk with

a cinema rake, the back pews about a

metre higher than those at the front, the

sight-lines focused on the high altar. I

remember Christine Garrod telling me that

"The slope is very gentle, but we do

have to warn funeral directors".

Beyond the rake, a baptistery is

filled with light; it was reordered in

the late 1990s, and restored to use. The font

and cover are Cautley's design.

The most overwhelming

feeling you get from being inside All

Hallows is a sense of sheer devotion.

Here is something bigger than the world

outside, an uplifting from the mundanity

of material existence. I think it is no

coincidence that each of the main

Anglican parish churches on Ipswich's

large deprived estates - Chantry,

Gainsborough, Whitehouse and Whitton - is

High Church in character.

Rick Tobin asked me if I

would like to go up the tower. Now, I

have a great fear of heights. I have been

told that this is irrational, but I am

not so smug as to think that the laws of

gravity do not apply to me. I'm also sure

that, when my head starts to swim as I

look down, this is my body's way of

telling me to stay away from the edge.

However, as with people who are afraid of

spiders (how ridiculous!) I am always

willing to try a little aversion therapy.

Richard unlocked a narrow doorway, and I

expected to see a flight of steps, but

all that there was inside was electrical

equipment. I waited for him to flick a

few switches and then show me the way to

the stairway, but instead he ushered me

into the cupboard. There, against the

wall, with a clearance from the organ

works of about 18 inches, was a shaft

leading upwards into darkness, a black

iron ladder fixed flush to the wall. My

heart started to flutter with panic, but

having come thus far I began the climb up

into the gloom. I could feel the shaft

pressing against me as I clung on for

dear life. I climbed higher and higher.

Suddenly, I became aware that the space

was opening out behind me. I am not sure

which was worse, the confined space

within the shaft, or the feeling that at

any moment I would be falling backwards

into the darkness. After about twenty

five feet or so, I suppose, I came to the

top of the ladder. I had reached the

level of the internal church roof, and

slightly behind me above my head was a

narrow trapdoor. I now saw with horror

that I would need to let go of the

ladder, reach up to open the trapdoor,

and then lean back into empty

space to climb through the gap. Beyond

the trapdoor, the ladder would continue

within the dark void of the tower space.

At this point, my sense of

self-preservation kicked in, like an

angry dog who wakes to find a

particularly smug cat tucking into his

food bowl. What had I been

thinking of? Shaking, breathless with

anxiety, I carried my sense of vertigo

back down to dear, sweet mother Earth. I

won't be doing that again in a hurry, but

no doubt I shall dream of it regularly

for nights to come. Rick Tobin was very

understanding.

So, how did Cautley come to

design an Art Deco building? Well, he

didn't really. He's using the language of

Art Deco, but he's still thinking

Medieval. Witness the clerestory

above the transepts, the blind arcades in

the nave walls, the brick arches on

creamy columns reminiscent of Polstead.

There is the baptistery,

the transepts

themselves, the Lady chapel. The

Victorian Gothic benches that come from

Ely Cathedral, and the medieval bell from

a disused Norfolk church.

Whichever way you

look at it, this is a delightful,

inspirational building, one which

deserves many more visitors than it gets.

It is also the heart of a vibrant, living

faith community; a power station indeed.

|

|