| |

|

You would not

think to look for St Michael unless you knew. These days,

a concrete track runs across a nearby field, and

approaches the church through the woods at the rear. But

even then, the building is hidden from view, and you

might easily miss the turning if it wasn't for a sequence

of hand-lettered signs. Better, perhaps, to reach the

tight little graveyard across the fields - after all,

that's been the way for the last 1000 years or so. There

is no village to speak of, and the parish is a scattering

of hidden lanes without any focus, a patchwork of woods

and farms.

St Michael was an estate church in the grounds of Boulge

Hall. But the Hall was demolished in the 1950s. Much of

the grounds had been turned over to cultivation during

World War II, and only the copse of ancient trees marks

out this space among the fields, and the tower seen from

the Debach road. And yet, St Michael receives many

visitors. The church's fame rests on the memory of one

person - or, more accurately, two. Boulge Hall in the

19th century was home to the Fitzgerald family. Their

name is everywhere in the church, they virtually rebuilt

it. Their huge mausoleum, for many years on the Buildings

at Risk register, has been restored, and broods

magnificently beneath the tower. But it is one of the

Fitzgerald sons not buried in the mausoleum who is the

goal of so many pilgrimages. Edward Fitzgerald was born

at adjacent Bredfield. He moved to Boulge Hall when his

parents bought it, and then spent most of his adult life

living in Woodbridge, where a museum documents his life

in some detail, although generally glossing over certain

aspects of his life. In 1859, he translated the Rubiyat

of Omar Khayyam from the Persian, thus establishing

himself as responsible for one of the most famous, and

enduring, pieces in English literature. He died in 1883,

and was buried here. The church is the goal of Fitzgerald

pilgrimages, but also of those paying homage to Omar

Khayyam.

Fitzgerald is buried

in his own grave, beside his family's mausoleum. The

gravestone is long and sombre, typical of the period. A

rose bush at the head of the grave is supposed to come

from a cutting taken from Omar Khayyam's grave in Iran.

It was planted by the Omar Khayyam society, and one

assumes that cuttings are regularly taken from it in turn

by visitors. Fitzgerald is probably second only to

Benjamin Britten in his fame as a creative artist from

this part of Suffolk. If Britten's homosexuality was

barely acknowledged in his lifetime, you can bet that

Fitzgerald's wasn't at all. But for both of them, their

sexuality seems to have been an important part of their

genius, and in recent years Fitzgerald's friendship with

a Lowestoft fisherman has been movingly documented.

Apart from the tiny 16th century tower, completed on the

eve of the Reformation, the exterior of the church is

thoroughly 19th century, tidy and tight and rather sweet.

It conceals one of the most atmospheric Victorian

restorations in East Anglia, a time capsule of

late-Victorian sentiment. As you approach, the apparent

south door is in fact the vestry door, and you must go

around to the north side, where you can step through a

door in the north wall directly into the tiny nave. On a

sunny day this is a step into almost complete darkness,

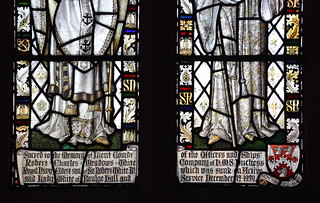

as your eyes struggle to adjust. The small windows are

full of thick late 19th and 20th century coloured glass

of the highest quality. Almost all of it is by Clayton

& Bell, including memorial windows to the soldiers of

the Suffolk Regiment killed in 1900 at Colesberg in the

Boer War and to all those killedwhen HMS Duchess sank in

December 1939 after being accidentally rammed by another

British ship. The only other workshop represented here is

that of AJ Dix who was responsible for the 1906 memorial

window in the Fitzgerald aisle. Subjects include the

archangels St Michael and St Gabriel, St Faith and St

Nicholas, Christ flanked by St Edmund and St Felix, the

Annunciation, the Baptism of Our Lord, and, somewhat

strikingly, Queen Victoria.

The overwhelming impression is of a peculiarly East

Anglian early 20th Century Anglo-Catholicism. It is

probably the best single collection of its kind in any

small church in the two counties. The Norman marble font,

primitive and brooding and quite different from its jolly

lion-bedecked cousin at nearby Ipswich St Peter, sits

beneath the tower now, and the tower itself contains one

of the bells rescued from the church of Mickfield when it

was abandoned in the 1970s. Its story is on the adjacent

wall.The restoration is a fairly early one of 1858, by

the Habershons. The church as you see it today is pretty

much as Fitzgerald would have known it.

Ahead of you as you enter, the south aisle is something

quite extraordinary, virtually a family shrine to the

Fitzgerald family. The family pew is surrounded by

memorials to family members, children, cousins,

grandchildren remembered in pious stone and glass. It is

a remarkable achievement for what was not a great landed

family. And what makes it all the more extraordinary is

that, within a few years of its completion, the

Fitzgeralds of Boulge had completely died out.To stand

here now is to be surrounded by the influence of a landed

family at a moment in history when, in an act of extreme

piety, they could ensure their place in posterity. Anyone

who loathes late-Victorian sentiment will not feel easy

here. But for the rest of us this is a marvellous place

that will remain long in the memory.

Simon

Knott, February 2020

Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England

Twitter.

Amazon commission helps cover the running

costs of this site

|

|

|