| |

|

| |

|

Antiquarians and

ecclesiologists have not been very kind to our

parish church, begins Terence Smith's

guidebook to this church. Certainly, they have

been dismissive, but I think this is a lovely

little church, even if it is not full of

interest. You come to it from Bradfield Combust,

along high tree-lined lanes that recall the

memory of Arthur Young senior, of Bradfield Hall,

who first planted them more than 200 years ago.

The Youngs are one of two remarkable families in

this area, but probably they would admit to

second place behind the St Cleres, who were Lords

of the Manor here throughout most of the Medieval

period. They were great crusaders, and the image

of St George in crusading armour at Bradfield

Combust, despite post-dating the crusades by two

centuries, may be based on a St Clere family

portrait.

Much has been made of the fact that this church

bears a unique dedication in England for a

medieval church. St Clare was a companion of St

Francis, and lived in the 13th century, by which

time the Parish system and its churches in

England was already well-established (there

aren't many St Francis dedications, either).

Sadly, and as you may have already guessed, it

isn't actually the case. As you often find over

the border in Essex, the village here is named

not after a Saint at all, but after the St Clere

family. (Although less common in Suffolk, this

type of village naming does occur in several

places, notably Ashbocking and Stonham Aspal).

The medieval dedication here was to All Saints,

not to St Clare. The modern dedication was

adopted as recently as the 19th century, and

although it would be possible to blame 18th

century antiquarians for making the mistake that

led to it (as is often the case) it seems an

entirely reasonable mistake to make. After the

Puritan era, and before the Oxford Movement

revival, Parish churches were usually named after

their villages. It seems natural that 'Bradfield

St Clere Church' could easily become 'St Clare's

Church'. However, the modern Parish has happily

adopted its new dedication, and why not?

You cross a steep railway bridge over the

now-vanished Sudbury to Bury line, part of which

is a footpath to the south of here. You enter a

hamlet of pleasant cottages, and the church is

away in the fields, with an incongruously large

water tower for company. The graveyard is

beautifully sheltered, if a little overneat. The

church itself also looks well cared for, its

exterior bearing witness to the fact that the

tower collapsed in a storm in 1873, and during

the rebuilding the opportunity was taken to

completely refurbish the rest of the structure.

All except the chancel and nave walls dates from

this time and later.

The church is kept locked with a keyholder

nearby. When I phoned, he briefly mistook my call

for one bothering him about solar panels or

mis-sold payment protection insurance, but

eventually we each worked out what the other was

talking about, and soon I stepped into a

gorgeously warm interior, all limewash and

polish. The church is full of light, the

whiteness of the walls reflecting the sunshine

pouring in through the high windows.

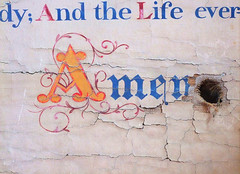

The Victorian

restoration was a good one, high quality

work that has aged well. In any case,

research has found little evidence that

anything of any value or interest was

destroyed by it; even in the late 18th

and early 19th centuries antiquarians had

found it, to quote David Davy, little

in any way interesting. Offsetting

the modern nave is the ancient chancel,

rebuilt in the late 15th century. The

roof is a delight, and again, light pours

in through the seriously perpendicular

windows. They give a sense that the

church is bigger than it actually is.

While I was finishing photographing the

interior of the church, a man and his

elderly mother arrived to have a look

inside. As is often the case in a small,

remote church, they were a little alarmed

to find someone already inside,

especially a wild-haired man in cycling

clothes, but we said hello to each other

politely. The man told me that he was

pleased and surprised to find the church

open, so I didn't disabuse him of this

notion. His mother went up into the

chancel, and the man confided in me

"she's trying to work out if she's

been here before, but it's not a very

memorable church, is it", with which

I had to agree, but I do like this church

a lot. I like above all its sense of

continuity, that here was a fairly simple

parish church that had been buffeted and

shaken by the winds of history, and had

responded by reflecting the changing

aesthetics, theologies and emotions of

its parishioners. |

|

|

|

|

|

Simon Knott, August 2014

|

|

|