| |

|

Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England

Twitter.

Here we are in the gentle yet secretive

hills to the east of Lavenham. It was April 2019, and I'd

come by the top road from Monks Eleigh, a lonely road

where cars rarely stray and grass grows up in the middle.

I imagined it was a bleak place in winter, probably

snowbound between the hedges. About halfway between the

two villages I was woken from my reverie by a large

roebuck jumping through a gap in the hedge across the

road about ten yards ahead of me. I brought my bike to a

swift halt, and watched in wonder as he was followed by

two more bucks, and then three, and then a couple more.

In the end I watched thirteen of them pass before me, as

big as calves.

They knew I was there. They looked back at me from a

field of shooting barley, their white rumps in a line.

And then they broke for cover, and were gone over the

rise.

Still full of this thrilling sight I freewheeled down

into the village until I reached the church. It had been

several years since my last visit, but I remembered much

about the place because St Mary is a church of

outstanding interest, but little known to those who rely

on older books for the churches they visit, for the great

treasure here was not discovered until 1961. Even without

knowing about it you can see that this is a lovely

village church, rebuilt with 14th Century wealth that

came from the cloth trade, for this was one of the

villages where wool was spun in river-backed courtyards

for the Lavenham merchants.

The name of the village reflects a dramatic event. At

some point in its history, it was destroyed by fire

(Brent='burnt'). Not far away, there is Bradfield

Combust, a name denoting a similar incident. The church

sits in a long sleeve of a churchyard, full of robust

birdsong in the late winter sunshine, its chancel pointed

towards the road. Externally, St Mary is that rare beast

in Suffolk, a largely late Decorated building. It looks

well on its rising ground. The old door with its ironwork

latch is probably the one provided by village carpenter

and blacksmith back in the 14th Century, a startling

thought. I lifted it, and once again I stepped into the

cool inside, a beautiful cool, ancient space, the walls

laid with brick, the 19th century furnishings immaculate.

Sam Mortlock was right to call it charming.

One of the stories that haunted me as a child was that of

Howard Carter finally discovering Tutankhamun's tomb in

the Valley of the Kings. If you remember, it was on one

of the last days, just before the money ran out. Carter

breaks a tiny hole in the seal of the door. He shines his

torch through at the treasures beyond. "What can you

see?" asks a breathless assistant. "Wonderful

things", whispers Carter.

In 1961, the Victorian reredos was removed from the

sanctuary of St Mary, to enable a repair to the east

wall. Traces of colour were visible behind the thin layer

of plaster. Gently, it was removed, revealing, as in

Carter's words, wonderful things, for here are some of

the finest and most beautiful wall paintings in Suffolk.

Most striking is the crucifixion scene above the altar,

forming a retable. The Blessed Virgin and St John flank

the crucified Christ. They date from the start of the

14th century, making them roughly contemporary with the

figures at Little Wenham and on the Thornham Parva

retable. They are similarly angular yet fluid, as though

in motion. These are doubly remarkable survivals, for

early in 2016 they were attacked by someone with a knife

or screwdriver, perhaps someone with an anti-religious

mania or a hatred of images. It took over a year for the

wallpainting specialist Dr Andrea Kirkham to collect

together thousands of flakes of plaster and paint and

restore them to their original place. You really would

not know to look at it today.

Either side of the reredos are slightly

earlier paintings, late 13th Century. To the left, two

angels censing a space with thuribles, and the space must

have contained an image bracket, probably for a

crucifixion, or perhaps an image of the Blessed Virgin.

But the most unusual scene is to the right of the

crucifixion. This shows the Harrowing of Hell. Christ

descends into Hell to free Adam and those condemned

before the arrival of salvation. But the most intriguing

feature is the figure kneeling in the bottom corner. He

is probably the donor, and part of his intecessionary

scroll survives.

There was a falling out of fashion for non-liturgical

wall paintings in the middle years of the 15th century.

Many seem to have been whitewashed then, a full century

before the protestant Reformation, not to see the light

of day again for nearly half a millennium. Perhaps the

two outer scenes were covered then, and the painted

reredos lasted until the Reformation itself.

Eerily, the scene in this central painting

is echoed in the 1860s glass by the O'Connor workshop

above, although of course the Victorians cannot have

known that they were doing so. And as if the wall

paintings were not enough, the sanctuary is contained

within another great treasure, the three-sided 17th

Century communion rails. There are fewer than half a

dozen sets of these in all East Anglia.

The box pews in the nave are complemented by some

surviving 15th century benches at the west end. At one

time, they may have faced the Decorated parclose screen

in the south aisle. It is slightly later than the wall

paintings, but you can begin to imagine the Catholic life

and liturgy of this place. Mortlock thought it the oldest

screen in Suffolk, and curiously St John is represented

on it by an eagle, more often on screens in East Anglia

he is shown by a poisoned chalice, the eagle surviving

elsewhere only at Sotherton in Suffolk and Magdalen in

Norfolk. The screened chapel later became a family pew.

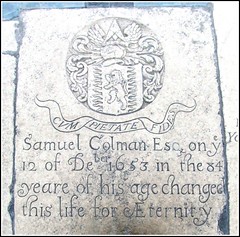

Up in the chancel is one of Suffolk's more dramatic

memorials. It is to Edward Colman, who died in the 1740s,

at a time when many English churches were falling into

disrepair, and no doubt welcomed the patronage of those

who wished to use the buildings as a kind of mausoleum.

Colman reclines life-size behind a spiked iron fence,

which looks as if it is there to stop him escaping. These

fences are typical of the period, but many must have been

removed during World War Two for scrap. There is a

pensive smile on his face, as if he is resigning himself

to the inevitable. High above, a crown in heaven waits

for him, clasped in the chubby arms of a cherub, and

Colman stretches out his left hand as if to receive it.

Colman's father is remembered for

bequeathing to the church a parish library of more than a

thousand books. They had their own building, which was

demolished in the restoration of 1860, but the volumes

had been dispersed some years earlier. Many can now be

found in university libraries around the world. The

memorial was apparently the work of Thomas Dunne, who

built churches for Hawksmoor. The Colmans, and other

parishioners, were baptised in the Purbeck marble font

with its elegant cover at the west end of the south

arcade. A beautiful light falling into this aisle

distracts from the height of the nave, which looks as if

it might have been waiting for clerestories and a north

aisle before the Reformation intervened. The north wall

is home to the royal arms of Queen Anne, relettered for

George I, a hatchment, and a surviving biblical

inscription from those days when the Elizabethan

Settlement tried to make us all into protestants.

The spring afternoon was almost over, a chill beginning

to make itself felt in the low sunshine. It was time to

head back to Ipswich. I wandered back down to the road in

the bright sunlight and headed north into the hills, the

haunting and beautiful church at Kettlebaston keeping me

company on a ridge to the east. I looked back to make out

the tower of Brent Eleigh church behind me. Soon, the low

hills enfolded it, and it disappeared.

Simon

Knott, September 2019

Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England

Twitter.

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Churches of East

Anglia websites are

non-profit-making, in fact they

are run at a loss. But if you

enjoy using them and find them

useful, a small contribution

towards the costs of web space,

train fares and the like would be

most gratefully received. You can

donate via Paypal.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|