| |

|

|

|

The border area between

Essex and Suffolk is one of England's

best-kept secrets. Away from touristy

Dedham Vale, the gentle hills rise higher

ever westward beyond the Stour. Here are

East Anglia's prettiest landscapes and

prettiest villages, especially on the

Essex side of the river. Bures has the

best of both worlds, being partly in

Suffolk and partly in Essex, that

much-maligned, lovely county. The Suffolk

part of the village is called Bures St

Mary, because the medieval parish church

is on the Suffolk side of the river. It

has the pubs and the shops. You cross

into Essex and enter Bures Hamlet, part

of the parish of Lamarsh. Here is the

railway station. The war memorial outside

St Mary's church remembers The men of

Bures St Mary and Bures Hamlet who gave

their lives for King and Country in the

Great War, and is perhaps the only

war memorial in England to remember the

dead of not just two separate parishes,

but from two different dioceses in two

separate counties. The gentle river that

separates the two will sprawl out to half

a mile wide before it reaches the sea at

Harwich. |

As historic as St Mary's

church is, there is another building in Bures

which is of at least equal significance, and

which may be of older provenance. St Stephen's

chapel sits on the Suffolk side, above the

village but hidden from it. You leave town on the

road to Assington. After about a mile there

is a farmyard on the right, looking distinctly

unpromising with sheet metal buildings and

concrete hard-standing. A track leads through the

farmyard and then continues for about half a

mile. It doglegs eastwards suddenly, and there,

with just a cottage for company, is this long,

unassuming thatched building.

One

of the stories told about this place is that it

was the site of the coronation of Edmund, one of

the last kings of an independent East Anglia.

Edmund was crowned in AD 855, when he would have

been about 14 years old. The kingdom of East

Anglia and the neighbouring kingdom of Essex were

both already under attack by Viking raiders by

this time, and both would eventually succumb, so

it is not unlikely that the royal palace had been

moved inland from the coast away from Rendlesham,

the previous capital, and Ipswich, by then one of

England's largest towns. However, there seems no

evidence that this was the site of the coronation

other than a 13th Century medieval legend, and

nothing survives to tell of what might have been

here in the 9th Century. By AD 869 Edmund was

dead, slaughtered by Vikings at either Hoxne

(Suffolk) or Hellesdon (Norfolk), depending on

the county to which you owe allegiance. His

remains eventually ended up at Bedricsworth, the

modern Bury St Edmunds, and he was canonised by

the early medieval church as St Edmund. The

shrine at Bury was sacked at the Reformation, and

the remains today are believed to lie in the

crypt of Toulouse Cathedral in south-west France.

As

I say, there is no evidence to show whatever

might or might not have happened here, but

intriguingly, this remote Suffolk field was

considered important enough in 1218 for the

Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton, to

consecrate this chapel. Canterbury did hold land

in this area, as well as the patronage of the

important nearby parish of Hadleigh, but whatever

the reason for Langton's presence it must have

been significant. At the time, Edmund was

considered the patron Saint of England, a

situation which would change a century later when

Edward III associated St George with the Knights

of the Garter. Edmund's star would set as

George's rose, and the Reformation which

destroyed his shrine would see St Edmund largely

forgotten, but he remains today the patron Saint

of East Anglia and is vigorously championed in

some quarters as the true patron Saint of

England.

The original chapel forms the

easterly two thirds of the building. It was

consecrated on the Feast of St Stephen, December

26th 1218. At the Reformation, the need to blow

apart any devotion to the former King of East

Anglia meant that sites associated with St Edmund

had to be dealt with particularly rigorously. The

chapel was sacked, and once derelict was

converted for use as cottages, and then as a

barn. For the next four hundred years it was used

for agricultural storage. The north wall was

breached to allow access to large farm vehicles,

and later the building was extended westwards.

This extension is still used as a barn.

In the 1930s, the Badcock and

Probert families who owned it restored the

eastern part of the building as a chapel, and it

provided a home for some of the tombs of the De

Veres, the Earls of Oxford, which had previously

been at Colne Priory, just over the border. The

De Veres were the great family of this border

region, their star and boar decorating such great

churches as those of Dedham, East Bergholt,

Castle Hedingham and Lavenham among others,

including Earls Colne itself. They inherited

Colne Priory at the Dissolution, and used the

chapel there as their mausoleum until the early

18th Century. The three tombs here are amalgams

of perhaps eight that were at Earls Colne. Simon

Jenkins thought that the tombs were good enough

for him to include this chapel in his book England's

Thousand Best Churches, and there

is certainly a drama about finding them here in

this lonely spot.

The

impressive effigies of the De Veres are by no

means the only feature of interest here. At the

east end is a good collection of continental

glass of the 16th and 17th Centuries. It includes

two matching figures of St Mary Magdalene and St

Augustine, and a roundel showing the deposition

of Christ's body in the tomb. Of greater interest

still are two medieval panels, one depicting the

scourging of Christ which must once have been

part of a sequence, and another, fragmentary,

which appears to show the Mass of St Gregory, a

late medieval devotion in which the crucified Man

of Sorrows appears on the altar to the future

Pope as he celebrates Mass. This glass may well

all have come from the chapel at Earls Colne.

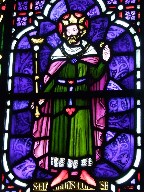

Three modern figures depict, in the 14th Century

style, St Edmund, St Edward the Confessor and St

Lawrence. Mortlock says they are by Henry

Wilkinson.

A

transept built on to the north side of the chapel

houses a mezzanine gallery which looks into the

body of the church. At the west end is a

continental statue of a bishop, which was

probably collected in the early 19th Century by

someone. Below it is what appears to be the shaft

of a late medieval font - can it have come from

here originally?

| Also at the west end is a

memorial in the Arts and Crafts style. It

shows an angel surrounded by foliage and

holding a memorial plaque. The

unfortunate effect is of a tortoise

flattened to the wall, but when you get

up close you see it is a memorial to

Isobel Badcock who died loving and

beloved in 1939. It records that she

took great joy in the restoration of this

her chapel and also remembers her

brother-in-law Geoffrey Probert, who

spent long hours here and contributed in

every way he could to make it the

perfect, lovely and worthy offering she

desired. The

narrowness of the building is accentuated

when you stand at the west end and look

eastwards. The massive tombchests give

something of the effect of boats floating

through a tunnel. At the far end, the

triple lancets beckon you to something

beyond them. This is a curious, lovely

place, inevitably unlike any other church

in East Anglia.

|

|

|

|

|

|