| |

|

|

|

Deep within the soil of

Suffolk, the germ of memory sleeps.

Generations forget; their history is

effaced, and they are left oblivious,

aware only of their surroundings. They no

longer ask how they got here. And then,

the soil is turned, the plough cleaves

the furrow, and the past is revealed. And

sometimes memory sleeps on the surface;

we do not even know that we have

forgotten.

Between about 1530 and 1570, England

underwent a cultural revolution, a

process as violent and traumatic as

anything that has happened in our

history. In less than half a century,

England went from being a complex and

clumsy melange of largely self-governing

Catholic communities which looked to Rome

as much as they did to London, to being

an insular and centralised Protestant

nation where power was maintained by the

sword.

The process was not complete. The

pendulum continued to swing, and by the

mid 17th century England had become a

theocracy, with political policy based on

an explosive mixture of Biblical

fundamentalism and a misguided sense of

destiny. At Drogheda, Cromwell's troops

would dutifully slaughter the women and

children of the town, safe in the

knowledge that they were doing God's

work. Of course, the evil they were

rooting out was the very religion that

their forefathers had shared, for

generations.

|

Suffolk retains one of the most

powerful testimonies to the glory of that former

age, and to the violence of its destruction. And

yet, for generations it was almost completely

forgotten.

Fifteen years have passed. It was Saturday,

September 9th, 2000. I stood in the ruins of the

great abbey of St Edmundsbury, writing the words

I am editing now. I was in what was probably the

scriptorium, where generations of monks copied

texts borrowed from other monasteries, or came

here to copy the monastery's own, building up the

great libraries of the Middle Ages. They worked

on the Gospels, and other books of the Bible.

They copied the works of the spiritual fathers,

and the classical histories.

The task was laborious, but was an act of prayer

and contemplation in itself. Even making the

materials became a meditation; the ink was

prepared in a base of egg white and honey; the

bright colours of the illustrations came from

crushing precious stones.

The atoms of silicon in those stones were

identical to the ones in the microchips inside

the laptop i was using that day. They converted

my words into a pure digital stream, which moved

at the speed of light as I uploaded it onto the

Suffolk Churches website, still in its infancy

then. The computers belonging to the users of the

site contained more of these silicon atoms, these

precious stones. They downloaded and reconverted

my digital stream into a language that was the

bastard son of the Latin in which the monks

wrote, the vulgar tongue of the townspeople

beyond the walls, and the Norman French of their

new masters.

I wandered through the chapter house, and into

the great north transept of the Abbey church

itself. The monks in the scriptorium made the

same journey, whenever the bells rang for the

daily offices. Now, I stood inside one of the

largest Romanesque churches in Europe. In my

mind, I lived and relived what it would have been

like to be here then.

Sometimes books aren't enough, and sometimes they

tell us what we'd really rather not know. Any

decent local history will tell you about the

glories of Bury Abbey, about its run-ins with the

local people, the riots and the riches, of how it

lived and died. Now, this is all very well, but

more interesting I think is the possibility of

sensing what it was like to live here as an

ordinary monk in, say, the 13th century.

Fortunately, the daily life of Bury Abbey is one

of the best documented of all lost medieval

communities. In the scriptorium that I had just

left, a monk called Jocelin of Brakelond wrote a

chronicle of this Abbey and its times; it is

effectively the story of the adolescence of the

county of Suffolk. A difficult time, with

troubles still to come.

For most people, there are two big surprises

about the ruins of the Abbey. Firstly, how

extensive they are, and secondly how tamed and

domesticated they appear in the large and

pleasant Abbey Gardens, in this most pleasant of

all East Anglian towns. The outer Abbey wall,

which housed and contained the Abbey

outbuildings, still survives to a greater extent,

forming the boundary of the park, and with some

very nice 18th and 19th century houses built into

it since.Two of the conventual churches, St James

(now the Anglican cathedral) and St Mary, survive

pretty well intact, along with a wall and charnel

house of a third, St Margaret. So do two of the

gateways; one is still the main entrance to the

park, and the other is considered one of the

finest survivals in England, temporarily houses

the Anglican cathedral bells.

But it is the ruins of the great Abbey church of

St Edmund that astound. A vast, cruciform

building, it was more than 500 feet long and 200

feet wide. You could fit Suffolk's biggest parish

church, St Peter and St Paul at Lavenham, into

the nave and transepts four times, and still have

room for Thornham Parva up in the sanctuary. It

is possible to trace the structure almost in

entirety, apart from the south aisle and west

front, which have been swallowed up by later

buildings.

And the setting! At the end of the apse are

municipal tennis courts, with an incongruous

bowling green tucked in beside the north

transept. A children's playground, a rose garden,

a museum (the 'St Edmundsbury Experience') all

surround it. You would be harsh to hate it, I

think, because it gives the people of the town a

sense of ownership; for these ruins are wholly

accessible at all times the park is open, and,

miracle upon miracle, entrance is completely

free.

So, how did this extraordinary

building come to be here? How is it that one of

the great churches of Europe was destroyed?

The story starts some 30 miles east of here, in

the village of Rendlesham, near Woodbridge.

Unlikely as it may seem, this was almost

certainly the capital of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom

of East Anglia. Today, despite being relatively

suburban, and on the edge of a large former

American airbase, there is still a haunting sense

of the remote past, enhanced by the forests that

ride the ridges of the heathland. Here lived the

Wuffingas, the Saxon royal family. Most prominent

among them was Redwald, King from 599 to 625. A

pragmatic man, he established his kingdom as one

of the primary trading areas of north west

Europe. In the Gipping valley, his quays,

workshops and settlements coagulated into

Gyppeswick, the modern Ipswich. By the 8th

century, it was the largest town we know of in

northern Europe.

We should not be surprised that his capital and

trading port were in the south east extremity of

his kingdom, any more than we should be surprised

that London, England's capital today, is also in

the south east. For Redwald was a European, a

federalist rather than an empire builder. For

him, it was trade rather than conquest that built

up his fabulous wealth. In an essential act of

embracing the European sphere, Redwald became a

Christian; but it was said that in his palace at

Rendlesham he kept two altars, one for the

Christian God he had adopted, and one for the

pagan gods of his forefathers, for he was a

pragmatist to the last.

And, at the last, his body was taken slowly in

procession from the Christian church at

Rendlesham, across the heathlands, until on

Sutton Hoo it was met by a huge ship which had

been dragged up from the Deben estuary below.

There, he was buried in it, along with weapons,

clothes, armour, musical instruments, jewellery,

symbols of sovereignty; the signs of his majesty

and trading might. His son, Sigebert, carried the

Christian torch after his death. And now,

Chritianity became a way for the Wuffingas to

reinforce their sovereignty.

Sigebert invited representatives of the Church

into his kingdom. From Burgundy came St Felix, a

beacon of Roman orthodoxy.From the monasteries of

the north came St Fursey, steeped in Celtic

spirituality. Later, from Germany, came St

Botolph, architect of monasticism. From his

cathedral at Dumnoc, the modern Walton, Felix

directed the consecration of Minsters in the

trading communities of the Kingdom. Sigebert also

turned to the monastic life. He set off

westwards, towards the limits of his kingdom, and

at a place called Bedricsworth established a

community of like-minded souls, the rest of their

lives devoted to prayer and contemplation.

Which might easily have been the end of the

story, of course; Bedricsworth was just one of

many Christian communities of the time. Some have

disappeared into oblivion, and it might have been

one of these. But there are others where the germ

of memory has thrived, and taken root. One of

these was a place called Lindisfarne, some 300

miles to the north. There, a similar community

were going about their morning round of prayer

and farmwork in the summer of the year 793, when

a group of long, low boats were sighted on the

eastern horizon. The boats landed on the shore

below the monastery, a place that is still a

harbour today. The sailors climbed to the

monastery, and sacked it. They killed most of the

monks, stole the produce of the farm and the

furnishings of the church, and burned the

monastery down. And then they left, returning to

where they had come from.

It was the Vikings, of course. Over the next

fifty years, the attacks of these Danish hordes

increased along the entire eastern seaboard, both

in number and ferocity. The Kingdom of East

Anglia was wide open to their depredations.

Gippeswyck was obvious game, the richest trading

port in the land. The Saxons, mainly farmers,

craftsmen and small traders, were powerless. What

the Kingdom needed was a hero.

His name was Edmund. From his headquarters at

Rendlesham, he set out to drive the heathen

invader from the land. A king leading his troops

into battle, he became more than a figurehead. He

was an icon. And then, in 869, in a parish called

Hellesdun, which was probably the modern Hoxne

but may have been Bradfield St George, he was

captured by Danish troops. In front of the

assembled Saxon prisoners, he was mercilessly

butchered, Danish troops firing hundreds of

arrows into his body at close range.

Who can separate legend from fact at such a

distance? The story is that the corpse was

decapitated, the head being thrown into a

thicket. Saxon soldiers dispersed in the battle

slowly returned, to find the headless body of

their king. They searched for three days, and

eventually came upon a giant wolf, guarding the

head of Edmund between its paws. The body was

taken to an unknown place called Sutton, which

may have been Sutton Hoo, or possibly Sutton in

the parish of Bradfield St George, or perhaps

somewhere else. Within a generation,

hagiographies were being written, Edmund's

sainthood secure.

The cult grew. Some fifty years after the

martyrdom, the remains were translated to the

Abbey at Bedricsworth; it became a major centre

of pilgrimage, as people came from all over to

seek the favours of the martyr king, the symbol

of resistance to the Danes. Within the century,

it is being called by its new name, the name it

has today, Burgh, or Bury, St Edmunds.

A few years later, came a crisis; the monastery

was no longer judged a safe place for the bones

to lie, either because of the Danish war, or more

likely the inefficiency of the community. It was

translated to London in 1010, where it lay in St

Paul's churchyard. In 1013 it was returned to

Bury, but only on the condition that the

community was replaced with one that followed the

rule of St Benedict. Secular priests had proved

unreliable.

The magnitude of Edmund's cult can best be judged

by the fact that at Domesday in 1086, the

monastery had 300 separate holdings of land

throughout the east of England. About 70 of them

were in the western part of Suffolk, including

Long Melford and Mildenhall, and almost the

entire area to the north and east of the

monastery itself, as far as the Norfolk border.

The Abbey had complete legal jurisdiction over

the eight Hundreds of West Suffolk, which was

known as the Liberty of St Edmund, and roughly

corresponded to the West Suffolk County Council

area which survived until 1974.

The Abbey church was rebuilt about this time, the

tomb of St Edmund being erected in 1095. The body

was translated into it with great ceremony, along

with the bodies of St Jurmin, brother of St

Etheldreda and son of King Anna of Blythburgh,

and what Norman Scarfe wittily calls 'at least

part of St Botolph'. It took another 100 years

before the rest of the building was finished. The

town around was built up, with the construction

of a grid of streets and hundreds of houses. It

was a medieval new town.

The monastery reached the apex of its power in

the late 12th century under the charismatic Abbot

Samson, familiar to East Anglians as a symbol of

the Greene King brewery. By now, there were about

a hundred monks and secular priests in residence,

and as many again of workers and servants.

Parliaments met here, monarchs arrived with their

retinues. History was made. The library became

one of the intellectual centres of Europe, with

more than 2,000 volumes. Visitors to the Abbey

describe it in the terms one would use of a great

city. It was the glory around which Suffolk

gathered and spread, the pulsing heart of all

power and spirituality.

Fortunately, it is still possible for us to see

what the Abbey church of St Edmund was like. We

can do so by travelling 30 miles to the north

west, to the tiny beautiful city of Ely in

Cambridgeshire. There, we find a Cathedral of

roughly the same proportion, configuration and

style. Replace Ely's famous lantern tower with a

spire, and the illusion is complete. The south

west tower of Ely survives (that to the north

west fell in the 17th century) and we can see the

same south west tower at Bury, surviving as part

of the building overlooking the square between St

James and St Mary. Here is a good place to start.

Beyond and beside are modern buildings, so to

explore the rest of the Abbey church ruins we

must go through the gate to the north-east of St

James - or, if this is locked, as it sometimes

is, back out on to Angel Hill, and into the park

through the Abbey gateway.

The best approach to the ruins is then found by

bearing right, up past the bowling green, and

into the conventual buildings beside the north

transept. These include the scriptorium and

chapter house, where we will find modern

graveslabs marking the site of the burials of

Samson and other former Abbots. We then step into

the north transept. Towering columns and walls

surround us; like melting icebergs, or wax. It is

easy to visualise them as the remains of walls

and pillars, but we need to be careful. What we

are seeing are, in fact, the remains of the flint

rubble cores. All that we see now would have been

hidden behind sheaths of dressed stone, a tiny

part of which survives, facing the base of some

parts of the ruin. What we see now was never

meant to be seen.

As we walk into the crossing, we can turn west to

look down the vast nave, the stumpy cores marking

the arcades that separated off the north and

south aisles. We can imagine the triforia above

them, and the roof far off beyond that. The great

pillars of the crossing are the most substantial

survivals, and we can see how they would have

supported the vaulting. Turning to face the east,

we must imagine the high altar some 70 feet

beyond, high in the sanctuary. Behind it stood

the tomb of St Edmund, after Canterbury and

Walsingham the greatest goal of pilgrimage in

Medieval England.

Your imagination needs to be slightly keener for

the chancel and the sanctuary, because the crypt

beneath has been exposed, and nothing of the

original floor level survives. In the crypt, we

see clearly the little chapels that led off the

central space, and cores and some modern slabs

mark the spots where columns supported the

vaulting above.

This crypt was excavated after the Second World

War, and in one of the chapels we see the stone

base of an altar, one of only three such

survivals in Suffolk - the others are at Orford

castle chapel, and the Ipswich Blackfriars

church. Now, children clamber and explore where

once prayer was offered and Masses celebrated. On

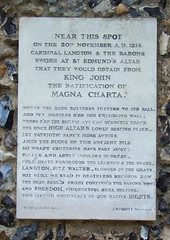

a plaque in the crossing, the meeting of the

Barons on the eve of Magna Carta is commemorated.

On the 20th of January 1465, a great fire ravaged

the Abbey. It destroyed all the roofs, and

brought down the central tower and spire. It

seems unlikely that they could have been

completely replaced in the short life the Abbey

had left. Earlier in its history, the Abbey had

had more than a few run-ins with the local

people. The main point of contention seems to

have been that the freedoms obtained in charter

form by other Boroughs were not made available to

those under the control of the monastery. In

1327, the townspeople rioted, and spent three

days occupying and trashing the Abbey.

The Abbot seems to have pacified them with a

charter of their own, but a revenge attack by

monks on the congregation of one of the churches

led to an ongoing civil war in the town that had

to be put down by the Sheriff of Norfolk. During

the Peasants Revolt of 1381, several prominent

government figures, including the Chief Justice

and the Collector of Taxes, sought refuge in the

Abbey; but by now there seems to have been

considerable collusion between the monks and the

townsfolk, for the refugees were handed over, and

publicly butchered in the market place. This

created such a scandal that Bury town and Abbey

were only readmitted to the King's Peace a year

after everywhere else in England.

We have a record of the last years

of the Abbey in the work of John Lydgate, who

came from the Suffolk village of Lidgate. He

records that the Abbey gave a quarter of its

income in relief to the poor of the Liberty, and

distributed food and alms at its gates daily. The

guesthouses were open to all, even the poorest of

pilgrims; St Edmund's Abbey was no longer a

centre for the wealthy.

In 1538, the monasteries were dissolved, their

possessions were sold off, and the monks all

given pensions. Senior monks that protested too

loudly were put to death. The money from the sale

of goods accrued to the crown, and the land also.

One intriguing question is what happened to the

body of Edmund at the Dissolution. Many Saints'

bones were desecrated and publicly exhibited,

paraded in the street before being burned, or

fashioned into clumsy weapons, musical

instruments or hockey sticks, in a grisly attempt

to demonstrate that they held no spiritual power.

The less ideologically-driven reformers were

conspiring to sell the relics abroad, reasoning

that the money European churches were willing to

pay for them could legitimately be counted as the

wealth of the church that was to accrue to the

state. So, were the bones of St Edmund sold or

desecrated? At the Dissolution, the commissioners

write of the huge size of the tomb, that it

was<i> comberous to deface</i>, and

mention the loot sequestered from the Abbey

itself, but there is no mention of the corpse of

St Edmund, and nothing to reveal its whereabouts.

In an elegant and fascinating essay entitled St

Edmund's Corpse: Defeat into Victory, the

late Suffolk historian Norman Scarfe recorded the

presence of a skeleton in the Cathedral of St

Sernin, Toulouse, labelled Corpus S Eadmundi

Regis Anglie ('The body of Saint Edmund,

King of the English'). This corpse was in the

cathedral certainly as early as 1270, and the

story that was current by the late 16th century

was that it had been stolen from the shrine at

Bury in the year 1216, during the anarchy of the

Barons' War.

Whoever this body was, it was offered back to the

English Church in 1901, at the time of the

consecration of Westminster Cathedral. Cardinal

Vaughan, the leader of the English Church at the

time, readily accepted the offer of renewing the

shrine in his new Cathedral, and the corpse was

brought by train to Dieppe, and thence to

Newhaven in Sussex, where it was kept in the

chapel of the Duke of Norfolk's house at Arundel,

until the new shrine was ready.

At this point, things started to go awry. A

correspondence in the press revealed the

considerable doubts of historians and theologians

that the corpse could possibly be that of St

Edmund. The Cardinal lost his nerve, and the

corpse was never translated to Westminster. And

so, at Arundel it remains, a century on. It could

be Edmund, I suppose. More likely, perhaps, the

bones were buried quietly at night by members of

the chapter, when it became clear what the

writing on the wall was saying. In which case,

they lie beneath the soil of Bury to this very

day.

After the Reformation, some great English Abbey

churches became cathedrals, but that did not

happen here. And yet, it so easily might have

done. Way back in 1070, some 500 years

previously, Herfast, Bishop of East Anglia,

decided to move his See from Thetford to Bury. It

had moved about a bit already over the previous

400 years, from Walton to North Elmham before

Thetford. But now, after the Norman Conquest, the

idea was that Cathedrals would be glorified;

already, vast edifices were being raised in

Durham, London and Ely. Bury was the obvious

place for the Diocese of East Anglia to sit.

However, such a move would have cut off the

Abbey's independent direct line with Rome, and

placed it under the jurisdiction of the Province

of Canterbury. The community was determined that

this would not happen, and Abbot Baldwin sent

representations to the Pope that ensured the

survival of the Abbey's independence.

Bishop Herfast would not be allowed to glorify

his position in East Anglia in the way his

colleagues were doing elsewhere. His successor,

Herbert de Losinga, was more determined. But Bury

was a lost cause; instead, he chose to move his

See to a thriving market town in the north east

of his Diocese; a smaller, more remote place than

Bury, to be sure; but proximity to the Abbey of

St Edmund was perhaps not such a good thing

anyway - it tended to cast a rather heavy shadow.

And so it was that the great medieval cathedral

of the East Anglian bishops came to be built,

instead, at Norwich.

Five hundred years later, the Dioceses of Norwich

and Ely, into which Suffolk evenly fell, were not

large; and, in any case, they were loyal to the

crown. The same could not be said of the Abbey,

where the community was still fiercely

independent of the State; as at Walsingham, of

course, where the Abbey church was destroyed even

more effectively.

For two centuries after the dissolution, the

Abbey effectively became a quarry for the people

of Bury, who carted off its stone for other

buildings. By the end of the 17th century, what

had happened here had been virtually forgotten.

The Protestant Cultural Revolution in England was

at its height. It wiped the people's collective

memory of their Catholic past. History was at

least resurfaced, if not selectively rewritten.

But the enlightenment of the 18th century saw a

rekindled passion for history, especially among

those with the leisure to pursue it. How

fascinating and remote these ruins must have

seemed by then! What stories the ordinary people

must have told about them!

With the 19th century revival came a new respect

for the medieval past, but it was not until the

1950s that these ruins were properly opened up to

the people of Suffolk, their true inheritance.

| My son, unlike me, was born

in Suffolk. I had him with me when I

visited on that September day in 2000. he

was seven. As with all children, he took

the ruins at face value. His mind can't

possibly reconstruct what was here

before. Instead, he invented universes,

oceans of possibility and imagination, as

far from the world today as that which

Abbot Sampson inhabited. He clambered on

the ruins with other children, the north

wall of the transept becoming a sea

cliff, the steps into the crypt a

Himalayan mountain path. As far as he was

concerned, anything might have happened

here. And that's what

archaeology mostly is, I suppose; it's

about narrowing down the possibilities.

It is about finding the cord that leads

all the way back.

People wander aimlessly about these ruins

- you'll never be alone here. Is this the

same spiritual thirst that sends them

into medieval churches? When they aren't

locked, that is.

Or is it something more

primal, some human need to open up a

perspective on where we have come from;

and thus, who we are. The Church of

Felix, Fursey, Botolph and Edmund has

undergone many changes in the 1300 years

or so since their adventures were played

out on the fields of Suffolk. Most

recently, at the Second Vatican Council,

it taught us about the Journey of Faith,

that life is a pilgrimage towards God.

And, of course, we've already come a long

way.

|

|

|

Simon Knott, September 2000,

revised and updated August 2015

|

|

|