| |

|

|

There

is no other church in Suffolk quite like All

Saints. Chelsworth is one of the prettiest

villages in Suffolk, and its church is only

approachable through someone's garden, as at

Cookley. This forces you to say hello to the

person putting out their washing, or strimming

their borders. I think this is lovely. The church

is no match for the village, I fear, being

cement-rendered and Victorianised inside.But it

is bold, and majestic, and seen across the fields

has a beauty of its own that none can match.

Chelsworth

is the thinking-person's Prettiest Suffolk

Village - much classier than blowsy Kersey. That said, as a cyclist I

prefer Kersey. Chelsworth's village street is a

ratrun for those taking the shortcut through Bildeston between Stowmarket and

Sudbury, and is no pleasure to wander along

anymore.

I try

to make it a habit to walk around a church before

going inside. This sounds easy, but so often I am

tempted to rush and see if the church is open,

and end up going inside first. All Saints repays

the effort of resisting this more than most; if I

tell you that I have never found it locked, and

even if it is you can pop back to the house and

ask them to open it, perhaps you will also walk

around it first. You will find, with some

surprise I hope, that the hidden south side is

even grander than the north, and that the amazing

beturreted south porch is no longer in use, but

has become a vestry. In its windows is reset 17th

Century continental glass, but these are locked

away from public sight. This side is a familiar

Perpendicular rebuilding of the late 15th

century; it reminds us that we are in Suffolk. As

a bonus, several of the buttresses still bear consecration crosses.

|

We now go

into All Saints from the north, and this porch has been

Victorianised in the nicest possible way. This

description holds true for the whole church, really;

there is an enthusiasm about Chelsworth which is tenuous

elsewhere. It is all done very tastefully, except for one

awful, dreadful mistake, which we will come to in a

moment.

Before going

in, you will have wondered at the extraordinary structure

set into the wall of the north aisle. Inside, this turns

out to be a huge 14th century tomb canopy. Mortlock argues that it was originally free-standing

before being sited here, presumably in one of the

arcades, but possibly up in the chancel, in which case it

might once have been an Easter

sepulchre. The

case is made for it being the tomb of Sir John Philibert,

who died in 1334. It is a magnificent piece.

The windows

are almost entirely glazed in 19th century glass of an

understated kind; although this is a big church, it

doesn't feel the least bit urban. You never doubt that

you are in a rural outback, so presumably Diocesan

architect Richard Phipson didn't get his hands on it. The

millennium window by Paul Quail at the west end of the

north aisle is barely noticeable, which is probably the

best thing that can be said about it.

| Above the chancel

arch, there is a doom painting. These are rare

enough survivals, given that most churches must

have had them. Unfortunately, the people who

found it in the 19th century thought it was so

significant that they repainted it. Now,

it sits up there in garish colours as a testimony

to Victorian ignorance; which is a shame,

considering the good things they did elsewhere

here. The rainbow in particular, on which Christ

sits, looks as if it has been done for a

children's party in the 1970s. A

significant family in these parts in years gone

by was the Pocklingtons. They have a hatchment,

and several memorials, but the most interesting

is probably to Sir Robert Pocklington, who died

in 1840. He was a knight of the military order of

Maria Theresa, created as such in the late 18th

century by Francis II, the last emperor of the

Holy Roman Empire. Legend has it that Pocklington

saved the emperor in person from the attentions

of the French. I wonder what they made of that in

this rural outback?

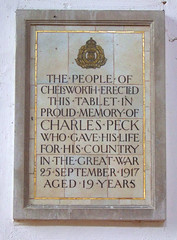

Another

name worthy of mention is Charles Peck.

Incredibly and mercifully, this village of more

than 300 people lost only one of its sons to the

horror of the First World War. He was 19 when he

died in September 1917, a teenage innocent on the

killing fields of Flanders. Because of this, he

gets the pretty little war memorial all to

himself. Across the church, a memorial to John

Venables Scudamore, killed at Gallipoli, reminds

us that he too was born in this parish.

|

|

|

Simon

Knott May 2003, updated July 2015

|

|