| |

|

|

|

Here we are half a dozen

miles from the pleasant town of Bury St

Edmunds, and Chevington is one of those

fat, comfortable villages, of which west

Suffolk has so many. The church is away

from the centre of the village at the end

of a long lane which sets off in the

direction of Ickworth House. All Saints

is not a well-known church, but in its

way it is remarkable, a building that it

is as beautiful as it is interesting.

This is a large church, in a wide, trim

graveyard, and rather fortress-like with

its red brick battlements. It imposes

itself on us in a way that is less

familiar in west Suffolk than we might

find in the grand, remote churches of

Norfolk, say. The castellated south side

appears stark, though not unpleasing. The

spirelets on the 15th century tower were

later additions, intended to provide a

'view' from Ickworth House, as at Westley

St Mary. The true age of the nave is

obvious from the south doorway, which is

a grand Norman affair. It was obviously

considerably heightened in the late

medieval period. Was an aisle intended,

and even a clerestory? The chancel

appears low and functional beside it. |

You step into the surprise of

whiteness and light. Everything is perfectly

arranged, everything engages the eye and lifts

the spirit. The use of whiteness and space

creating a sense of the numinous. The chancel was

reordered in the 1980s, and no punches were

pulled in creating a fitting and purposeful space

for late 20th century worship. It is reminiscent

of many Catholic churches of the period in the

way it has dispensed with clutter and created a

sense of openness, and although this is a CofE

parish church, the spirit of Vatican II has been

warmly embraced. The whole piece feels

devotional, and prayerful.

Ironically, this is one of the few Suffolk

churches that was not thoroughly restored in the

second half of the nineteenth century. This is

due to an accident of history. A restoration here

in the 1820s took away the roodloft stairs, as

well as the remains of the rood screen, and was

therefore probably structurally necessary. A

major restoration then took place in 1910, at

which time a heavy wooden screen was put across

the chancel arch. This, thank goodness, has now

been removed, and one of the most delightful

chancel interiors in the county is revealed. The

floor had been lowered at the end of the 17th

century, and now a horseshoe of bricks was built

up as a communion platform.

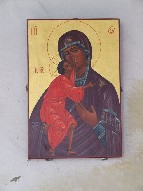

A new altar was put in place, along with a

reservation pillar, affirming the Anglo-catholic

tradition of this parish. The east window, an

unusual date of of 1697, contributes to this

sense of simplicity and lightness. The lightness

of this space is enhanced by the openings either

side of the chancel arch. Something similar

exists a few miles off at Gedding. These would

once have had altars in front of them, giving a

view of the high altar. They date from the 13th

century, so would have pre-dated any rood system.

You can still find a piscina beside the southern

one.

This quiet spirituality has a

dramatic counterpoint, however. In common with

several churches around here, the font shows

signs of iconoclastic attack. The panel on the

west side has had a great chunk taken out of it,

probably with an axe, and crude graffiti in a

17th century hand has been scrawled in one of the

shields. As the font carries no religious

imagery, the iconoclasm must have been intended

as an attack on the idea of infant baptism

itself.

The best is yet to come, for as you

return westwards you will find the surprise of a

range of 15th Century bench ends, depicting

musicians and other figures, and it is hard not

to think they may have been based on the late

medieval inhabitants of this lovely village. The

best of the musicians plays the bagpipes, and

others accompany him on the double shawm, the

lute, the tabor and the nakers. Other figures

pray with rosary beads, and one holds what

appears to be a nosegay on a stick. Their quality

may be a result of this church being in the

ownership of Bury Abbey until the Reformation.

The

17th Century has left its treasures as well.

Under the chancel arch are two similar ledger

stones: a winged hourglass and a cherub flutter

over the inscriptions Sin shall be no more:

Blessed are ye Dead which Die in the Lord. There

is a quiet simplicity to them, fitting in this

church, and the theme is continued by a sequence

of simple memorials on the chancel walls: in

1901, Cyril Miles died aged twelve and a half from

the effects of a gun accident in New Zealand.

The

following year, the Rector's son George White

fell in the moment of victory while gallantly

leading the storming party at Gumatti Fort in the

Waziri Expedition. In 1915, his nephew John

White, son of the next Rector, was killed at

Gallipolli at the age of 24, three illustrations

that the early years of the last century were

also dramatic in their effect upon a rural East

Anglian parish.

|

|

|