| |

|

This is a church

of great interest, despite its Victorian makeover. But

first, you will have to find it. There are fleeting

glimpses on the road from the village of Creeting St

Mary, but, closer, the church is completely hidden by the

trees that surround it. It lies at the end of a gravel

track, about a third of a mile from the road. This is

signposted, but the sign is also obscured by trees. A

secret, hidden place. And yet, from the corner of the

graveyard can be glimpsed the vast paint factory complex

at Stowmarket in the valley below. And St Peter is

separated from its village by the four lanes of the A14,

the roar of which can be heard from the churchyard. How

has this happened? Simply, Creeting St Peter consists

mainly of council houses and farm cottages, working

people's houses. People like this do not get asked if

they want a motorway at the bottom of the garden.

I first came here on a day of the high summer of 1998,

when the trees were boiling with green. Coming back on a

fresh spring day in 2007, I found the graveyard full of

light. Two men with a Commonwealth War Graves Commission

white van were busy beside the path, resetting a

headstone. In the summer of 2019 the trees boiled again,

and a heavy silent heat lay across the churchyard.

The tower is a pretty, Victorianised one from the 15th

century. It bears obvious signs of substantial recent

repairs, as does the porch below. The most striking thing

about the outside of the church, though, is the series of

knapped flint crosses on several of the buttresses. Each

is about 90cm high, and there are five of them. However,

seven other buttresses show signs of repair where the

cross would have been, making twelve in all. Almost

certainly, then, these were external consecration

crosses, a rare survival.

You step into a church which is open to pilgrims and

strangers every day. It is gloomy at first, especially on

a summer's day, but as your eyes become accustomed to the

light you see what is perhaps the most remarkable feature

of the church on the north nave wall, the upper part of a

great St Christopher wall painting. The colours are

dulled, but the painting is highly detailed, although it

is a little hard to decode at first, because the top of

St Christopher's head has been obscured by a roof beam,

and the Christ child appears to be the central figure.

Once you've seen that he is sitting on the shoulder of a

larger figure, all is clear. The important survival is

that this St Christopher retains its scrolled Latin

inscription, which translates roughly as Whosoever

regards this image shall feel no burden in his heart

today. Much of the lower part of the image has been

destroyed, but a detail survives in the bottom right hand

corner of a mermaid holding a mirror and comb.The

greatest fear of late medieval Christians was a sudden

death, leaving their sins unconfessed. Intercessory

prayers were made to St Christopher for protection

against such an eventuality, and this made him one of the

most visible and significant parts of the 15th century

economy of grace.

Creeting St Peter

church was derelict by the 18th century, so we have the

Victorians to thank for its survival. Theirs is the roof,

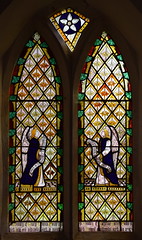

the furnishings, windows and sanctuary, and it is all

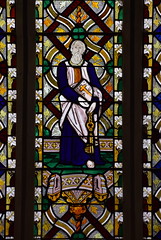

well done. The east window is particularly interesting,

as it predates the Victorian stained glass industry. It

was made by a Rector of the church. It shows St Peter, so

we may assume that this is one of the county's earliest

responses to the Oxford Movement-inspired revival of

interest in medieval theology and sacramental art. The

pulpit is slightly older than the other furnishings, and

if you climb up into it you will see that it is

heptagonal, the only one I know in Suffolk.

Another curiosity is the font. It is almost identical to

that at Earl Stonham, four miles away, but unlike that

one, this is in immaculate condition. Mortlock felt that

it hadn't been recut, and the carving is certainly in a

15th century style. There seems to be nothing missing,

except that the shields have no symbols on them. They

don't seem to have been attacked by iconoclasts. Perhaps

the font was never finished, but perhaps it is more

likely that it is a clever Victorian copy of Earl

Stonham's. Above the font, the 19th century gallery now

contains the organ, which was rescued from a London

church bombed in the Second World War.

Three fish swirl on the altar hanging, which is either by

the great Isobel Clover, or the work of one of her

pupils. On a quarry in a nave window is inscribed Be

still my soul with the musical notation above it.

They enhance the feel of what is obviously a well-loved,

well-used and looked-after church.

Simon

Knott, November 2019

Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England

Twitter.

Amazon commission helps cover the running

costs of this site

|

|

|