| |

|

|

|

This trim little church

conceals an extraordinary surprise. A

clue is in the picture above - tucked

away behind the rebuilt 19th century

flintwork you can see a red-brick

extension, stuck on the north side of the

chancel and hiding a view of the tower

from the east. For one moment you might

even think it was the Rector's garage.

This Denham is not to be

confused with Denham St John, thirty miles away

to the east. Here, we are in another tiny

village, but close to the large village

of Barrow, beyond the park

of Denham Hall, where at the time of my

first visit deer and wild boar were

farmed for the gourmet market. Coming

back in 2011, I didn't see anything so

exotic. The stables and farm buildings

behind the church have all been

modernised and converted into fine

houses, and a high hedge conceals the

graveyard from the road - indeed, if you

are not using an OS map, you may miss

this church completely, especially if you

are in a car. On my first visit, I had to

have two sweeps past on my bike.

The graveyard is as neat and

trim as the heavily restored church, and

genealogists will be disappointed to

learn that most of the old headstones

have been removed. However, it is all

obviously very well cared for, and loved.

|

The interior is

clean, rather dark and thoroughly Victorianised.

The font and furnishings are plain. I hope I will

be forgiven for saying that the nave is probably

of less interest than that of almost any other

medieval Suffolk church, although the sanctuary

is undoubtedly attractive. If you do not know

this church, you may wonder why I had been

looking forward to revisiting it with some

excitement.

On the occasion of

my first visit, back in the 1990s, I had not read

in advance about this church. I knew the west of

the county less well than the east, and in any

case enjoyed in those days visiting a church

unencumbered by other people's opinions. After a

wander around, I could get Mortlock out of my rucksack, settle down in

a pew and have a read. Imagine my surprise, then,

on wandering down towards the holy end, and

turning into another room off of the chancel. I

was confronted by one of the most extraordinary

monuments I have ever seen. It stands fully tweve

feet high, against the north wall of the chapel

(for that is what this building is). The eight

figures on it, not far short of life-size, are

Sir Edward and Lady Susan Lewkenor, who died of

Smallpox in 1605, and their six children arrayed

behind them. But they are dressed very much in

the fashion of the previous century. I was put in

mind of Dame Margarett Tylney, who is sleeping

through all eternity across the county at Shelley. But while Dame Margaret

lies in quiet piety, these figures are somewhat

more animated - one might even describe them as

looking like cartoon characters, their faces are

such primitive caricatures of human features.

Indeed,

I would go as far as to say that they don't

really look human. Their eyes are too close to

the top of their heads, for one thing. It is as

if some local amateur put in a speculatively high

tender for the work, and was surprised to get the

job. The boys look rather startled, as well they

might, but the girls look very serious, in their

ruffs and bonnets. They appear to be shuffling on

their knees into heaven.

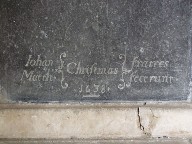

The

son of one of the two boys lies across the chapel

on his own monument. He is a later Sir Edward,

and he died in 1635. I assume that he had

something to do with this chapel being built, and

with the shoddy workmanship of his grandparents'

tomb. Whether or not that is the case, no expense

was spared for his own memorial; it is the work

of John and Matthias Christmas, favourites of

Charles I and carvers to the Royal Navy; Johan

Matth. Christmas Fratres Fecerunt 1638,

reads the subscription ('John and Matthias, the

Christmas Brothers, made this, 1638'). Hand on

heart, he lies peacefully in his armour, while

two cherubs gaze on.

This

second Sir Edward Lewkenor was the last of his

line; the Lewkenors of Denham Hall were not

embroiled in the bloody civil war which was

already brewing on the western horizon, but their

house and park have survived, as we have seen.

| The

juxtaposition between the chapel and the

chancel is not unlike that at Boxted, not far off,

although of course there is no aisle

here. When Arthur Mee came this way in

the 1930s, he found the chapel screened

by iron railings, which may have been

original. Whatever, they are gone today,

and there is no trace of them. I wondered

if they may have been surrendered to the

national interest during World War II.

Now, the chapel serves a dual role, for

it is also the church vestry. Back

outside, I wandered around for a while.

The redbrick stables which form a

boundary to the western side of the

churchyard are very attractive. Around

the corner of the church in the south

side of the churchyard, tucked away

behind the chapel, there are some

interesting modern headstones to members

of the Byford family. One to Nicholas

Byford remembers that he was a civil

engineer on the London Underground. The

traditional vines entwine themselves

around train tracks, and a London

Underground train emerges from behind the

foliage.

|

|

|

|

|

|