| |

|

|

|

It was one of those lovely

days in the high summer of 2016, and I

came here from Norfolk with my friend

John. We came through the beautiful

coolness of the Forest, hundreds of

shades of light green dappling the glades

either side of the road, almost all the

way to Elveden. In the thirteen years

that had passed since my last visit to

this church, something rather wonderful

had happened to the village, and to its

grand church. When I'd come this way

before I had taken my life in my hands to

cross the road, for the A11 main road

between London and Norwich passed through

the village, becoming its main street.

The traffic was slowed to a mere 50 mph,

although it was often much slower than

that thanks to Elveden being a

bottleneck, which was probably just as

well. If a car hits you at 50 mph, you

are not going to survive. As you approach Elveden,

there is Suffolk’s biggest war

memorial, to those killed from the three

parishes which meet at this point. It is

over 30 metres high, and you used to be

able to climb up the inside. Someone in

the village once told me that more people

had been killed on the road in Elveden

since the end of the War than there were

names on the war memorial. I could well

believe it. But now the

village has been bypassed, and it was a

pleasure to wander across the village

street and enter a churchyard full of

birdsong rather than of traffic fumes. If

Elveden church is no longer a landmark on

the journey between London and Norwich,

then this is an accolade which it can

well do without.

|

And

in any case, those

swept along in the stream of traffic were

unlikely to appreciate quite how extraordinary a

building this is. For a start, it has two towers.

And a cloister. And two naves, effectively. And

yet if you had seen this church before the 1860s,

you would have thought it nothing remarkable. A

simple aisle-less, clerestory-less building,

typical of, and indistinguishable from, hundreds

of other East Anglian flint churches. But it was

to undergo three fabulously bankrolled building

programmes in the space of thirty years, any one

of which would have sufficed to transform it

utterly.

The story of the

transformation of Elveden church begins in the

early 19th century, on the other side of the

world. The leader of the Sikhs, Ranjit Singh,

controlled a united Punjab that stretched from

the Khyber Pass to the borders of Tibet. His

capital was at Lahore, but more importantly it

included the Sikh holy city of Amritsar. The

wealth of this vast Kingdom made him a major

power-player in early 19th century politics, and

he was a particular thorn in the flesh of the

British Imperial war machine. At this time, the

Punjab had a great artistic and cultural

flowering that was hardly matched anywhere in the

world.

It was not to last. The

British forced Ranjit Singh to the negotiating

table over the disputed border with Afghanistan,

and a year later, in 1839, he was dead. A power

vacuum ensued, and his six year old son Duleep

Singh became a pawn between rival factions. It

was exactly the opportunity that the British had

been waiting for, and in February 1846 they

poured across the borders in their thousands.

Within a month, almost half the child-Prince's

Kingdom was in foreign hands. The British

installed a governor, and started to harvest the

fruits of their new territory's wealth.

Over the next three years, the British gradually

extended their rule, putting down uprisings and

turning local warlords. Given that the Sikh

political structures were in disarray, this was

achieved at considerable loss to the invaders -

thousands of British soldiers were killed. They

are hardly remembered today. British losses at

the Crimea ten years later were much slighter,

but perhaps the invention of photography in the

meantime had given people at home a clearer

picture of what was happening, and so the Crimea

still remains in the British folk memory.

For much of the period of the war, Prince Duleep

Singh had remained in the seclusion of his

fabulous palace in Lahore. However, once the

Punjab was secure, he was sent into remote

internal exile.

The missionaries poured in. Bearing in mind the

value that Sikh culture places upon education,

perhaps it is no surprise that their influence

came to bear on the young Prince, and he became a

Christian. A year later, he sailed for England

with his mother. He was admitted to the royal

court by Queen Victoria, spending time both at

Windsor and, particularly, in Scotland, where he

grew up. In the 1860s, the Prince and his mother

were significant members of London society, but

she died suddenly in 1863. He returned with her

ashes to the Punjab, and there he married. His

wife, Bamba Muller, was part German, part

Ethiopian. As part of the British pacification of

India programme, the young couple were granted

the lease on a vast, derelict stately home in the

depths of the Suffolk countryside. This was

Elveden Hall. He would never see India again.

With some considerable energy, Duleep Singh set

about transforming the fortunes of the moribund

estate. Being particularly fond of hunting (as a

six year old, he'd had two tutors - one for

learning the court language, Persian, and the

other for hunting to hawk) he developed the

estate for game. The house was rebuilt in 1870.

The year before, the Prince had begun to glorify

the church so that it was more in keeping with

the splendour of his court. This church,

dedicated to St Andrew, was what now forms the

south aisle of the present church. There are many

little details, but the restoration includes two

major features; firstly, the remarkable roof,

with its extraordinary sprung sprung wallposts

set on arches suspended in the window embrasures,

and, secondly, the font, supported by eight

elegant columns. Mortlock tells us it is in the

Sicilian-Norman style.

Duleep Singh seems to have

settled comfortably into the role of an English

country gentleman. And then, something

extraordinary happened. The Prince, steeped in

the proud tradition of his homeland, decided to

return to the Punjab to fulfill his destiny as

the leader of the Sikh people. He got as far as

Aden before the British arrested him, and sent

him home. He then set about trying to recruit

Russian support for a Sikh uprising, travelling

secretly across Europe in the guise of an

Irishman, Patrick Casey. In between these times

of cloak and dagger espionage, he would return to

Elveden to shoot grouse with the Prince of Wales,

the future King Edward VII. It is a remarkable

story.

Ultimately, his attempts to save his people from

colonial oppression were doomed to failure. He

died in Paris in 1893, the British seemingly

unshakeable in their control of India. He was

buried at Elveden churchyard in a simple grave.

The chancel of the 1869 church is now screened

off as a chapel, accessible from the chancel of

the new church, but set in it is the 1894

memorial window to Maharaja Prince Duleep Singh,

the Adoration of the Magi by Kempe & Co.

Curiously, one of the Magi has a real portrait

face. It isn't Duleep Singh, so who could it be?

And so, the Lion of the North had come to a

humble end. His five children, several named

after British royal princes, had left Elveden

behind; they all died childless, one of them as

recently as 1957. The estate reverted to the

Crown, being bought by the brewing family, the

Guinnesses.

Edward Cecil Guinness, first Earl Iveagh,

commemorated bountifully in James Joyce's 1916 Ulysses,

took the estate firmly in hand. The English

agricultural depression had begun in the 1880s,

and it would not be ended until the Second World

War drew the greater part of English agriculture

back under cultivation. It had hit the Estate

hard. But Elveden was transformed, and so was the

church.

Iveagh appointed

William Caroe to build an entirely new

church beside the old. It would be of

such a scale that the old church of St

Andrew would form the south aisle of the

new church. The size may have reflected

the Iveaghs' visions of grandeur, but it

was also a practical arrangement, to

accommodate the greatly enlarged staff of

the estate. Attendance at church was

compulsory; non-conformists were also

expected to go, and the Guinnesses did

not employ Catholics.

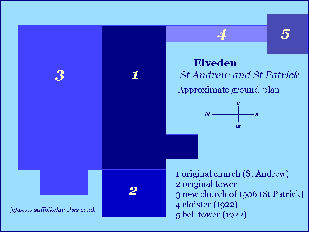

Between 1904 and 1906, the new structure

went up. Mortlock recalls that Pevsner

thought it 'Art Nouveau Gothic', which

sums it up well. Lancet windows in the

north side of the old church were moved

across to the south side, and a wide open

nave built beside it. Click on the plan

to the right to see an enlarged version.

Curiously, although this is much higher

than the old and incorporates a

Suffolk-style roof, Caroe resisted the

temptation of a clerestory. The new

church was rebenched throughout, and the

woodwork is of a very high quality. The

dates of the restoration can be found on

bench ends up in the new chancel, and

exploring all the symbolism will detain

you for hours. |

|

|

The new church

was dedicated to St Patrick, patron Saint of the

Guinnesses' homeland. At this time, of course,

Ireland was still a part of the United Kingdom,

and despite the tensions and troubles of the

previous century the Union was probably stronger

at the opening of the 20th century than it had

ever been. This was to change very rapidly. From

the first shots fired at the General Post Office

in April 1916, to complete independence in 1922,

was just six years. Dublin, a firmly protestant

city, in which the Iveaghs commemorated their

dead at the Anglican cathedral of St Patrick,

became the capital city of a staunchly Catholic

nation. The Anglicans, the so-called Protestant

Ascendancy, left in their thousands during the

1920s, depopulating the great houses, and leaving

hundreds of Anglican parish churches completely

bereft of congregations. Apart from a

concentration in the wealthy suburbs of south

Dublin, there are hardly any Anglicans left in

the Republic today. But St Patrick's cathedral

maintains its lonely witness to long years of

British rule; the Iveagh transept includes the

vast war memorial to WWI dead, and all the

colours of the Irish regiments - it is said that

99% of the Union flags in the Republic are in the

Guinness chapel of St Patrick's cathedral.

Dublin, of course, is famous as the biggest city

in Europe without a Catholic cathedral. It still

has two Anglican ones.

Against this background then, we came to Elveden.

The church is close to the road, looking entirely

19th Century apart from the tower from this side.

The main entrance is now at the west end of the

new church. The surviving 14th century tower now

forms the west end of the south aisle, and we

will come back to the other tower beyond it in a

moment.

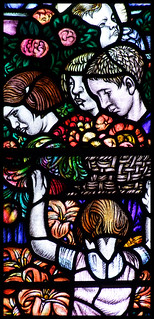

You step into a wide open space under a high,

heavy roof laden with angels. There is a wide

aisle off to the south; this is the former nave,

and still has something of that quality. The

whole space is suffused with gorgeously coloured

light from 19th and 20th century windows. These

include work by Kempe & Co, Hugh Easton,

Laurence Lee but most all one by Frank Brangwyn,

at the west end of the new nave. Depicting

Charity and Education, it shows Saints Andrew and

Patrick look down from a heavenly host on a

mother and father entertaining their children and

a host of woodland animals by reading them

stories. It is quite the loveliest thing in the

building.

The other windows are

mostly in the south aisle. Hugh Easton's

commemorative window for the former USAAF base at

Elveden depicts an angel sheltering an American

airman, his plane and the airbase behind him.

Either side are windows to Iveaghs - St George

kills a dragon to the east, also by Hugh Easton,

and to the west is Laurence Lee's abstract of

1971 depicting images from the lives of Edward

Guinness's heir and his wife.

The parish war memorials

are on the west wall, with twenty-nine names for

the First World War and just two for the second.

The churchwarden told me how moving the first two

minute silence after the bypass was opened was.

'It was the first time we've ever had a proper

silence', she said poignantly.

Turning back east towards the new chancel, there

is the mighty alabaster reredos. It cost £1,200

in 1906, about a quarter of a million in

today’s money. It reflects the woodwork, in

depicting patron Saints and East Anglian

monarchs, around a surprisingly simple Supper at

Emmaus. This reredos, and the Brangwyn window,

reminded me of the work at the Guinness’s

other spiritual home, St Patrick’s Cathedral

in Dublin, which also includes a window by Frank

Brangwyn commisioned by them. Everything is of

the highest quality. Rarely has the cliché

‘no expense spared’ been as accurate as

it is here.

Up at the front, a little brass plate reminds us

that Edward VII slept through a sermon here in

1908. How different it must have seemed to him

from the carefree days with his old friend the

Maharajah! Still, it must have been a great

occasion, full of Edwardian pomp, and the glitz

that only the fabulously rich can provide. Today,

the church is still splendid, but the Guinesses

are no longer fabulously rich, and attendance at

church is no longer compulsory for estate

workers; there are far fewer of them anyway. The

Church of England is in decline everywhere; and,

let us be honest, particularly so in this part of

Suffolk, where it seems to have retreated to a

state of siege. Today, the congregation of this

mighty citadel is as low as half a dozen. The

revolutionary disappearance of Anglican

congregations in the Iveaghs' homeland is now

being repeated in a slow, inexorable English way.

You wander outside, and there are more

curiosities. Set in the wall are two linked

hands, presumably a relic from a broken 18th

century memorial. They must have been set here

when the wall was moved back in the 1950s. In the

south chancel wall, the bottom of an egg-cup

protrudes from among the flints. This is the

trademark of the architect WD Caroe. To the east

of the new chancel, Duleep Singh’s

gravestone is a very simple one. It is quite

different in character to the church behind it. A

plaque on the east end of the church remembers

the centenary of his death.

Continuing around

the church, you come to the surprise of a

long cloister, connecting the remodelled

chancel door of the old church to the new

bell tower. It was built in 1922 as a

memorial to the wife of the first Earl

Iveagh. Caroe was the architect again,

and he installed eight bells, dedicated

to Mary, Gabriel, Edmund, Andrew,

Patrick, Christ, God the Father, and the

King. The excellent guidebook recalls

that his intention was for the bells

to be cast to maintain the hum and tap

tones of the renowned ancient Suffolk

bells of Lavenham... thus the true bell

music of the old type is maintained. The

bell tower has a double purpose, for to

the south of it we leave the churchyard

and enter the grounds of Elveden Hall.

The Iveaghs would come by carriage from

the Hall on a Sunday, dismount in the

space beneath the tower and walk along

the cloister to enter the church.

St Andrew and St Patrick is magnificent,

obviously enough. It has everything going

for it, and is a national treasure. And

yet, it has hardly any congregation. So,

what is to be done? If we continue to

think of rural historic churches as

nothing more than outstations of the

Church of England, it is hard to see how

some of them will survive. This church in

particular has no future in its present

form as a village parish church. New

roles must be found, new ways to attract

visitors, involve local people and

encourage new uses. One would have

thought that this would be easier here

than elsewhere, although I am afraid I

must report, as an end-note, that this

church is still kept locked without a

keyholder notice. |

|

|

|

|

|