| |

|

|

|

It had been so long since I

last visited Great Barton that I really

did not remember the village at all. It

is a large place, a bit of Bury St

Edmunds broken off really, only the

railway line separating it from the

Moreton Hall Estate. The church sits a

good half mile from the village, down a

narrow dusty lane. A large hare sat on

the road in front of me as I left the

village, and loped along just ahead in no

particular hurry until we reached the

church gates, where he turned and looked

at me, and then preceded me into the

graveyard. It was hard not to imagine

that he was an omen of some kind. Holy

Innocents is one of those spectacular

15th Century rebuilds that East Anglia

did so well, and is all the more so for

being so remote. Mortlock calls it

'handsome', which is about right. The big

tower rides high above the clerestory and

aisles, the long, earlier chancel

extending beyond. It has much in common

with Rougham, just across the A14.

Windows to aisle and clerestory create

something of the wall of glass effect so

beloved of the later Middle Ages.

Unusually, there is a tomb recess in the

outside of the south wall of the chancel

which was possibly for the donor of the

chancel.

The 15th Century south porch

carries a later sun dial with the

inscription periunt et imputantor,

which means something like 'they perish

and are judged'.

|

You

step inside to a big church. Despite the windows

of the south aisle being filled with coloured

glass, the church is full of airy light and

space. This is accentuated by the hugeness of the

chancel arch, which goes with the 13th Century

chancel - that is to say, nave and aisles were

built to scale with it as a starting point. In

such a great space the furnishings do not

intrude, and they are pretty much all the work of

the 19th Century restoration here. They are a

good counterpoint to the spectacular glass of the

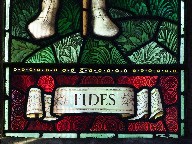

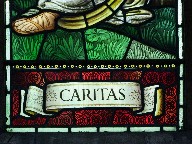

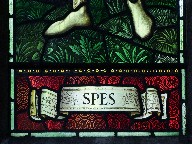

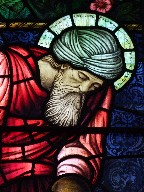

south aisle. The first window is by the William

Morris workshop, with the figures by Edward

Burne-Jones of Faith Hope and Charity. All three

are shown, unusually, as men. Faith is the Roman

centurion at the foot of the cross, Hope is

Joshua and Charity is the Good Samaritan.

Beside

it is a window which is somewhat bizarre. A

number of Suffolk churches have windows to

commemorate the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria

in 1887, but none, I think, are quite like this

one. The stately queen sits with a look of

indigestion upon her face among angels carrying

her crown and the Bible. She is flanked by two

rather unlikely fellow monarchs, the Queen of

Sheba with a snake of temptation and her motto Wisdom

is better than rubies and a positively

louche Queen Esther with If I perish, I

perish. Above Victoria's head in a scroll is

inscribed In her tongue is the Law of

Kindness from the Book of Proverbs. All in

all, a remarkable piece.

Ther

other window in the aisle depicts the Ascension

flanked by the Nativity and the Resurrection. The

Nativity scene is particularly good. It is

unsigned, but I wondered if it was by AK

Nicholson.

But

for the oddest window of all, you have to step up

into the chancel. Here, on the south side, is

another depiction of the Resurrection and the

Ascension. These appear in the upper part, and in

the lower part are the Disciples watching the

Ascension and the Roman soldiers asleep at the

Resurrection. However, these lower parts have

been put under the wrong upper parts, and the

sleeping soldiers are missing the Ascension and

the Disciples are watching the Resurrection! Such

a blunder can only have happened in the studio,

when the cartoons were being laid out before the

glass was made.

Holy Innocents is an

interesting dedication, and an unusual one for an

Anglican church, especially a medieval one. Bear

in mind that, in the Middle Ages, churches were

dedicated to feast days, especially of Saints,

and not the Saints themselves. Holy Innocents is

celebrated on December 28th, and remembers

Herod's massacre of the babies of Bethlehem. It

would have been a more common dedication in

medieval times. Here, it is probably a relic of

Anglo-catholic days, and the 19th century revival

of church dedications; but it may also be the

original dedication of the church. It is quite

clear that this church enjoys a High Church

character this day, and is one of the few village

churches in the Bury area where you can light a

candle when you say a prayer.

| Like all good High Church

parishes, Great Barton keeps Holy

Innocents open every day, and there is

even a Fair Trade shop where you can make

your purchases and perform a work of

mercy at the same time, a fine

opportunity. Back

outside, the churchyard is one of the

best in Suffolk to potter about in. It is

vast, with a good 300 years-worth of

headstones. While exploring, you might

notice that the very north-east corner of

the churchyard is cordoned off by a low

brick wall, and contains but a small

number of graves. They are to the Bunbury

family, who are also remembered with

mural monuments in the chancel of the

church. The

Bunburys had lived at Barton Hall, but it

was destroyed by fire in 1914. Sir Henry

Bunbury achieved a place in popular

history in the early 19th century when he

was the foreign office official who had

the job of breaking the news to Napoleon

that he was to be exiled to St Helena.

The school history books that speak of

the defeat of Napoleon have long since

been consigned to the skips. Now, all

that remains is the light summer breeze

in the corner of a Suffolk churchyard.

|

|

|

|

|

|