| |

|

I always get a frisson out

of visiting Gislingham, because it is one of the

few East Anglian churches with Knotts lying in

the churchyard. Here, the large, deeply incised

headstones to the west of the tower speak of

solid mid-Victorian respectability, and although

none of these Knotts have any connections to me,

I find this strangely comforting. When my son was

a teenager he especially liked the one which

begins James Knott fell asleep, because

that is his name, and he had a large photographic

reproduction of that headstone up above his bed.

One of my favourite sights of the red brick tower

of St Mary is that from the walks on the Thornham

Estate of the Hennikers. One can imagine the 18th

Century squires treating it as a 'view' and

planting their copses accordingly. Closer to, the

tower dominates the local countryside, grand, yet

mellow, one of the best red brick towers in

Suffolk. Within the village itself the church is

set rather tightly against the northern side of

its churchyard, but the tower is a pleasing

counterpoint to the surrounding houses.

And the tower is unusual, because it was built as

a replacement for a medieval tower in the years

after the Reformation. The neglect that set in

the Church of England in the later part of the

16th Century would cause more than a few Suffolk

church towers to collapse during the course of

the next two hundred and fifty years, before the

Victorians stepped in to rescue them.

Gislingham's was one of the first to fall,

hitting the ground in the winter of 1598. Robert

Petto paid for the replacement in 1639, so it was

probably an act of Laudian piety, and one that

would have seemed heartily pointless through the

twenty years of the Commonwealth period that

followed. Come the Restoration, however, and John

Darbye of Ipswich would cast two bells for the

tower - he may be the same John Darbie who had

given £100 for its construction thirty years

earlier. Because of the early date, there are

ecclesiological features which would be lost to

brick towers for the next couple of centuries.

Unusually, St Mary presents its north face to the

village street, with the grand porch and busy

graveyard belying any popular modern notion that

the north side of graveyards were in some way

unconsecrated. The tower was rebuilt flush with

this side, not centrally as before. St Mary is a

big church, and looks all of its forty metres

long. You enter through the long north porch and

the church you step into feels wide and open,

with a sense of age not scoured by the 19th

Century restoration. There is a fine

double-hammerbeam roof which allows the great

width of the church without any need for arcades.

Sam Mortlock spotted pulleys on several beams,

which were probably used for pulling up candle

lights.

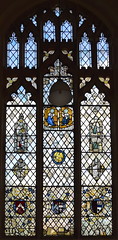

St Mary has a good collection of fragments of

medieval glass. The most significant scene is a

Coronation of the Blessed Virgin, which is more

commonly found in Norfolk. More beautiful are the

fragmentary collections set below it, including

one composite figure carrying the wheel symbol of

St Catherine, and elsewhere a face, a foot,

flowers and foliage and an exquisite roundel of

the eagle symbol of St John the Evangelist.

The church has undergone a

lot of repairs in recent years, and for anyone

who has visited it over that time it has looked

increasingly fine. The font has suffered the

knocks and indignities of the centuries, but

bears a dedicatory inscription to the Chapman

family, who also gave the porch outside. The

sanctuary, with its dark wood rails and

panelling, is beautiful in this ancient space.

There are some box pews retaining their numbers,

and the position of the three-decker pulpit

halfway down the nave reminds us of the

importance of preaching of the time. It is a

reminder that, for a couple of centuries, it was

the pulpit rather than the altar which was the

focus of worship in an Anglican church. Of

course, the Oxford Movement put a stop to that,

and in any case I think the pulpit part of the

structure is a modern replacement.

Gloomy skulls peep from beneath drapery on the

wall monuments. Elaborate tracery from the

medieval rood screen is set on the north chancel

wall. Sam Mortlock bemoaned its absence in 1987,

when he described the condition of the inside of

the church as being one of filth and decay.

How very different things are today!

|

|

|