| |

|

Moving east from the agri-industrial plains

to the north of Bury St Edmunds, you reach an area of

secretive, pretty villages, and Great Livermere is one of

them. It is one of several villages edging Ampton Water,

and to the west of the church the landscape is fairly

wild and rugged, punctuated by the broken tower of the

ruined church of Little Livermere, about half a mile

away.

Great Livermere church is a beautiful, organic building,

at ease in its rural setting, with the sense of being a

touchstone. The thatched roof has recently been renewed.

The tower was possibly never finished. Today, it is

topped by a weather-boarded belfry, which is both

singular and attractive. All around, there are windows

from almost every period, but at the heart of it all is a

nave which was once, broadly speaking, a Norman church. A

curiosity on the north side is the battlemented vestry

with its wooden traceried windows, probably a sign of the

pre-ecclesiological gothick of the first decades of the

19th Century. The church is an attractive assemblage,

despite (or possibly because of) the chancel and the nave

looking as if they are separate buildings which just

happened to be beside each other.

You step into an interior which is entirely rustic, but

perfectly cared for. The building is full of light -

there is no coloured glass at all - and this gives it a

feeling of being larger than it really is. As well as a

couple of consecration crosses, there are some surviving

wall-paintings, but most are long gone, and those that

remain are faded. The most interesting is opposite the

south door, which may not be the St Christopher you'd

expect, but possibly part of a 'Three Living and Three

Dead', as at Kentford.

The rood screen is strikingly good, dominating the

relatively narrow nave. There are gilded eagles in the

spandrels. Unusually, low-side windows are set beyond on

both sides of the chancel. One set still has its shutters

intact. These openings were intended to allow a bell to

be rung at the consecration in the Mass, and to increase

ventilation and updraught around the rood. There seems to

be no valid liturgical or devotional reason for there to

be a window in both sides, although it isn't a bad idea.

Cheerful hedgehogs scuttle through the quarterings of the

17th Century Claxton ledger stones in the sanctuary. The

three-sided communion rails that surround them are

probably a Georgian imitation of an early 17th Century

local fashion, perhaps replacing what was there before,

but many of the pews are from the previous century. There

are still pew numbers around the panelling. The

three-decker pulpit is a very fine one, a fruit of the

Church of England's confidence in the years after the

Restoration of the Monarchy. There is a carved, wooden

royal arms for Victoria.

At the west end, a hanging sign depicts a falcon, and

records an inscription to be found on a barely legible

headstone outside for William Sakings, who died in 1689,

and was forkner to King Charles I, King Charles II

and King James II. Leaning on the base of the

beautiful and simple 14th century pulpit is part of an

18th century memorial discovered under the floorboards.

It probably came from outside, because there is one with

very similar lettering just outside the south porch.

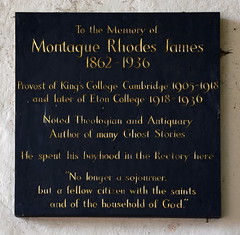

Church historians and fans of ghost stories alike will

pay homage to the M R James memorial in the chancel. The

author of the erudite 1920s travelogue Norfolk and

Suffolk, and the classic Ghost Stories of an

Antiquary, he grew up here, and his father was the

Rector.

Simon

Knott, July 2019

Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England

Twitter.

Amazon commission helps cover the running

costs of this site

|

|

|