| |

|

|

|

St Andrew is one of five

medieval churches in the Sudbury urban

area, and there are several more

separated from it by no more than a field

or two. But two of the Sudbury churches

are now redundant, and only St Gregory in

the town centre is open every day. When I

first came this way ten years ago I'd

found St Andrew locked without a

keyholder notice, but I'd been informed

by several people that there was now a

more enlightened attitude. Cornard is

Sudbury's busy southern suburb,

straggling along the road into Essex, and

its church speaks more of the southern

county than it does of Suffolk, the

wooden broach spire a near-twin of that

at lonely Great Henny a mile or two off

across the river. Image

niches at the west end would have

contained statues in late medieval times,

beneath which travellers might have

stopped for private devotions. The west

face of the tower sits hard against the

road, and so it wasn't until we reached

the churchyard that my heart sank. The

entire chancel was under scaffolding, and

that usually means an inaccessible

church.

|

Indeed,

the porch was locked, but a nice lady cutting

through the churchyard told us where the Rectory

was. The Rector was very pleased to see us and to

give us a go with the key, albeit warning us

about the work going on in the chancel. And so it

was that we hastened back along the high street.

From this side you can see that St Andrew was

substantially rebuilt during the 19th Century.

The south aisle, to which we were heading, dates

from the 1880s, and of course we could not see

the chancel, although I remembered that it is

largely still of the 14th Century. We unlocked

the porch and stepped inside St Andrew.

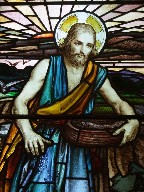

The

first impression on passing through the south

doorway is quite how little this church is. It

has the aisles and arcades you would expect of a

proud late medieval church, or a Victorian

imagining of one, but everything is done on a

small scale. My second impression was that this

was a busy place which was well-used, giving a

cluttered feel which was not unattractive. And

then, turning towards the east, my eyes were

caught by this church's one great treasure, a

1920 window by AJ Dix. It is outstanding of its

kind, and compellingly modern. It illustrates the

story of the sower who went forth to sow. The

lower left section depicts Christ sowing seed

broadcast from a basket ('A sower went forth to

sow his seed' reads the caption), and then two

angels gather in the harvest ('Some fell on good

ground and sprang up and bare a hundredfold').

Only the traditional face of Christ betrays how

close we are to the 19th Century. The faces of

the muscular female angels carrying sheaths are

utterly contemporary, as if they might be

suffragettes. The story proceeds anticlockwise

into the upper lights, where a horned devil grins

wickedly as he sows tares ('Tares are the

children of the wicked one'), and then two male

angels burn the resulting weeds ('The harvest is

the end of the world').

The

subject seems to have been a popular one locally,

and there is another good window at Colne

Engaine, a few miles off in Essex, by Reginald

Bell. There are a couple of 19th Century windows

which are relatively mundane, but even with the

chancel blocked off there was plenty of light

inside the nave. I happened to know that the east

window is fairly large with five lights, and so I

expect this is never a gloomy place.

| Looking at the booklets and

posters, and an impressive if startling

painting of a crucified, winged Christ, I

got the impression that this is a fairly

radically evangelical community, and full

of life. And Great Cornard has a history

of radical action: this is one of just four

Suffolk parishes which stood up to the

puritan iconoclast William Dowsing. Dowsing arrived

here early in the morning of 20th

February 1644 - it was the first visit of

a series he would make to churches in the

Sudbury area over a period of four days.

He must have been full of energy. He took

up two brass inscriptions which asked for

prayers for the souls of the dead,

because the puritans considered these

superstitious. He gave orders for the

cross on the tower to be removed, and

also that the chancel steps, which had

been raised twenty years earlier during

the Laudian attempt to reintroduce

sacramental liturgy into the Church of

England, should be levelled again.

However, the churchwarden John Pain

refused to pay for this work, and so

Dowsing had him arrested. What happened

to John Pain is not known, but he must

have been a brave man.

|

|

|

|

|

|