| |

|

|

|

This is a church I

seem to revisit every five years or so,

and I'm always left wondering why I don't

come back more often. After the longest

winter I can remember, and a good five

months since my previous church exploring

bike ride, I set off from Bury St Edmunds

on a bright, cold Saturday morning

towards the end of February 2018, and

Great Saxham was my first port of call.

Nothing much had changed. A large oak

tree had fallen near to the fence of the

park in a recent storm, but otherwise it

was exactly as I remembered. It is always

reassuring to cycle off into rural

Suffolk to find that England has not

entirely succumbed to the 21st Century.

But Suffolk has changed in the

thirty-odd years I've been living here.

There is hardly a dairy farm left, and

not a single cattle market survives in

the county. Ipswich, Lowestoft, Bury, and

even the smaller places, are ringed by

out-of-town shopping experiences, and the

drifts of jerry-built houses wash against

the edges of nearly every village. But

the countryside has always been in a

state of perpetual change, a constant

metamorphosis, and often a painful one. I

had been struck by this before while

cycling across this parish, and the

memory added a frisson to the experience

of coming back. |

For many

modern historians, the Long 19th Century finished

on August 4th 1914, and you can see their point.

That was the day that the First World War began,

and the England that would emerge from the mud,

blood and chaos would be quite different. A new

spirit was abroad, and rural areas left behind

their previous patterns of ownership and

employment that were little more than feudalism.

Suffolk would never be the same again.

No more the Big House, no more the farm worker

going cap in hand to the hiring fair, or the

terrible grind to keep at bay the horrors of the

workhouse. I think of Leonard, remembering the

pre-war days in Ronald Blythe’s Akenfield,

that passionate account of a mid-20th century

Suffolk village, Charsfield: I want to say

this simply as a fact, that Suffolk people in my

day were worked to death. It literally happened.

It is not a figure of speech. I was worked

mercilessly. I am not complaining about it. It is

what happened to me. But the men coming home

from Flanders would demand a living wage. The new

world would not bring comfort and democracy

overnight, of course, and there are many parts of

Suffolk where poverty and patronage survive even

today, to a greater or lesser extent, but the old

world order had come to an end. The Age of

Empires was over, and the Age of Anxiety was

beginning.

The English have a love-hate relationship with

the countryside. As Carol Twinch argues in Tithe

Wars, it is only actually possible for

British agriculture to be fully profitable in war

time. In time of peace, only government

intervention can sustain it in its familiar

forms. Here, at the beginning of the 21st

century, British farmers are still demanding

levels of subsidy similar to that asked for by

the mining industry in the 1980s. With the UK's

exit from the European Union looming, the answer

from the state is ultimately likely to be the

same. British and European agriculture are still

supported by policies and subsidies that were

designed to prevent the widespread shortages that

followed the Second World War. They are half a

century out of date, and are unsustainable, and

must eventually come to an end.

But still sometimes in Suffolk, you find yourself

among surroundings that still speak of that

pre-WWI feudal time. Indeed, there are places

where it doesn’t take much of a leap of the

imagination to believe that the 20th century

hasn’t happened. Great Saxham is one such

place.

You travel out of Bury westwards, past wealthy

Westley and fat, comfortable Little Saxham with

its gorgeous round-towered church. The roads

narrow, and after another mile or so you turn up

through a straight lane of rural council houses

and bungalows. At the top of the lane, there is a

gateway. It is probably late 19th century, but

seems as archaic as if it was a survival of the

Roman occupation. The gate has gone, but the

solid stone posts that tower over the road narrow

it, so that only one car can pass in each

direction. It is the former main entrance to

Saxham Hall, and beyond the gate you enter the

park, cap in hand perhaps.

Looking back, you can see now that the lane

behind you is the former private drive to the Big

House, obviously bought and built on by the local

authority in the 1960s. It is easy to imagine it

as it had once been.

Beyond the gate is another world. The narrowed

road skirts the park in a wide arc, with woods

off to the right. Sheep turn to look once, then

resume their grazing. About a mile beyond the

gate, there is a cluster of 19th century estate

buildings, and among them, slightly set back from

the road beyond an unusually high wall, was St

Andrew.

There was a lot of money here in the late 18th

and early 19th Centuries, so that you might even

think it a Victorian building in local materials.

But there is rather more to it than that. Farm

buildings sit immediately against the graveyard,

only yards from the church. When Mortlock came

this way, he found chickens pottering about among

the graves, and like me you may experience the

unnervingly close neighing of a horse in the

stables across from the porch.

The great restoration of this church was at a

most unusual date, 1798, fully fifty years before

the great wave of sacramentalism rolled out of

Oxford and swept across the Church of England.

Because of this, it appears rather plain,

although quite in keeping with its Perpendicular

origins - no attempt was made to introduce the

popular mock-classical features of the day. The

patron of the parish at the time was Thomas

Mills, more familiar from his ancestors at

Framlingham than here. There was another makeover

in the 1820s.

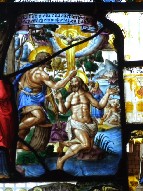

I've always found this church open, and so it

should be, for it has a great treasure which

cannot be stolen, but might easily be vandalised

if the church was kept locked (I wish that

someone would explain this to the churchwardens

at Nowton). The careful restoration

preserved the Norman doorways and 15th century

font, and the church would be indistinguishable

from hundreds of other neat, clean 19th century

refurbishments if it were not for the fact that

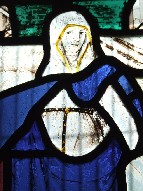

it contains some most unusual glass. It was

collected by Thomas Mills' son, William, and

fills the east and west windows. It is mostly

17th century (you can see a date on one piece)

and much of it is Swiss in origin. As at Nowton,

it probably came from continental monasteries.

The best is probably the small scale collection

in the west window. This includes figures of St

Mary Magdalene, St John the Baptist and the

Blessed Virgin, as well as scenes of the

Annunciation, the Coronation of the Queen of

Heaven, the Vision of St John, and much more. The

work in the east window is on a larger scale,

some of it Flemish in origin.

There are several simple and tasteful Mills

memorials - but the Mills family was not the

first famous dynasty to hold the Hall here. Back

in the 16th and 17th centuries, it was the home

of the Eldred family, famous explorers and

circumnavigators of the globe. John Eldred died

in 1632, and has one wall-mounted bust memorial

on the south sanctuary wall, as well as a figure

brass reset in the chancel floor from a lost

table tomb. Both are gloriously flamboyant, and

might seem quite out of kilter with that time, on

the eve of the long Puritan night. Compare them,

for instance, with the Boggas memorial at

Flowton, barely ten years later. But, although

the bust is of an elderly Elizabethan, I think

that there is a 17th Century knowingness about

them.

The

inscription beneath the bust reads in

part The Holy Land so called I have

seene and in the land of Babilone have

bene, but in thy land where glorious

saints doe live my soule doth crave of

Christ a room to give - curiously,

the carver missed out the S in Christ,

and had to add it in above. It might have

been done in a hurry, but perhaps it is

rather a Puritan sentiment after all,

don't you think?

The brass has little shields with

merchant ships on, one scurrying between

cliffs and featuring a sea monster. The

inscription here is more reflective,

asking for our tolerance: Might all

my travells mee excuse for being deade,

and lying here, for, as it

concludes, but riches can noe ransome

buy nor travells passe the destiny.

The First World War memorial remembers

names of men who were estate workers

here. And, after all, here is the English

Church as it was on the eve of the First

World War, triumphant, apparently

eternal, at the very heart of the Age of

Empires. Now, it is only to be found in

backwaters like this, and the very fact

that they are backwaters tells us that,

really, it has not survived at all.

|

|

|

|

|

|