| |

|

There are two

separate villages of Hacheston, Upper and Lower. Lower is

down on the A12, but All Saints is in the Upper village.

The church sits on the busy road between Framlingham and

Wickham Market, and thousands of people must pass it

every day. It is perhaps an undistinguished church at

first sight, although the tower is dramatic from the

road, which has cut down beside it. On the north side of

the graveyard is the huge Arcedeckne mausoleum, as big as

a garage. It seems to sulk from being so cut off, for the

north side of the church is not the more attractive

aspect. On the south side, the early 16th century south

aisle is beautiful and lends a quiet grandeur to what

would otherwise be a fairly small church.

Unusually for Suffolk, but as at neighbouring Parham, you

step directly through the west door into the space

beneath the tower and into the lovely church, with its

patina of age that the Victorians failed to erase. All

Saints was the very last stop on William Dowsing's grand

wrecking spree of 1644, and he had not run out of

enthusiasm or ideas, defacing imagery on the font and,

unusually, also taking the roodscreen to task.

Presumably, it hadn't been vandalised enough by the

Anglican reformers of a century earlier. Since the 1880s

restoration, the roodscreen panels have been relocated to

the west end of the nave, around the font. The Saints are

badly damaged. They appear to have been a set of the

Apostles, and you can still make out St Jude, St Simon

and St James.

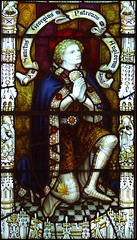

There are some quietly good examples of late 19th and

early 20th Century glass workshops. The window depicting

the raising of Dorcas on the north side of the nave is by

Lavers & Westlake. St George and St Martin flank

Christ in Majesty in Bryans & Webb's 1919 east

window, the war memorial. The same workshop was also

responsible for the Presentation in the Temple in the

south aisle. Another quiet survival is the 17th Century

pulpit, simply reset on a podium by the 19th Century

restorers.

Every medieval church had its rood of course, and

although none survive thanks to the efforts of Edward

VI's cronies, some of the tympana to which they were

attached have. The Wenhaston Doom, ten miles away, is one

of the most famous in England, a richly painted setting

that backed the rood. After the Reformation, these

tympana were generally whitewashed, and had the royal

coat of arms fixed to them, along with a few well-chosen

verses to remind the common people who was in charge now.

Because of this, and a little ironically under the

circumstances, the tympana were generally removed and

destroyed by the Victorian restorers as not being

medieval enough. Only a few survive, and Hacheston's

doesn't, but the timbers that supported it are still in

place above the rood beam, an unusual survival.

Dowsing is blamed for a lot, but most of the damage done

to our medieval churches occured 100 years before he went

on his merry way. His was essentially a mopping up

operation. In the 1540s, the hooligan gangs of the

Reformation vanguard went on their drunken sprees. Their

main targets were images of the Blessed Virgin and the

Saints. By Dowsing's time, no relief or statue of a saint

survived in situ anywhere in Suffolk. Most were

destroyed, although some were sold abroad for a quick and

easy profit. A few, however, were either carelessly

discarded below floorboards or even rescued and hidden.

During the Victorian restorations of our English churches

several came to light, most famously in Suffolk the image

of the Adoration of the Magi at Long Melford. There is

one here, too, set in the wall of the south aisle. It

shows St Thomas touching the wounds of Christ, exquisite

in alabaster. The person who made it in 14th century

England could not have begun to imagine how unusual it

would one day be.

Simon

Knott, January 2020

Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England

Twitter.

Amazon commission helps cover the running

costs of this site

|

|

|