| |

|

Iken is one of

those fabulous spots that some people think of as their

favourite Suffolk place. Others come across it by

accident, as if it were a happy secret. And there must be

many people, I suppose, who do not even know that it

exists. The little thatched church on its mound jutting

out into the wide River Alde is part of the panoply of

Suffolk mysticism, an element in an ancient story of the

birth of England, of grey mists and sad, crying wading

birds swinging low over the mudflats, as if this were a

piece of Benjamin Britten's chamber music made flesh.

You may have seen this church without ever visiting it.

Its tower is the one you can see in the distance across

the marshes from Snape Maltings beyond Barbara Hepworth's

Family of Man, and there is another sight of it

on the main road to Aldeburgh. But these two

civilisations are far away, and the isolated church and

the dubious delights of shopping in the craft shops of

the Maltings seem to have nothing in common.

I hope I can begin to convey an impression of what this

place is like. Iken, pronounced eye-k'n, is one

of Suffolk's most extraordinary places, and anyone who

has ever been here will not easily forget it. Here, the

River Alde snakes through mudflats and around islands.

The reed beds shiver and flow in the silence, and the

avocet and curlew cry out in their isolation. As the

seasons turn, and even as the day passes, it can seem

different. Light plays exquisitely on the silver water,

or the wind comes from far away, and on a cold winter's

afternoon there are few places I'd rather be.

But I had not been back to Iken for years. And then it

was a bright, frosty day in January 2020, and it was

generally agreed by all that I needed some fresh air. So

we drove up to Snape Maltings, parked, and wandered up

through the marshes alongside the sleepy River Alde to

Iken. It was bitterly cold, and the footpath once you

left the boardwalk was a sea of slippery mud. But there

were quite a few people about and we greeted each other

cheerfully, and eventually the path emerged in the lane

just before the turn off to Iken church.

I was walking with my son James, and it brought back a

memory of almost twenty years before. On a gorgeous day

in November 2000 we had set off from Snape in the same

way with my friend Malcolm, Jimmy's godfather. We took

the same path through the marshes, following the river

eastwards. Jimmy, then seven, was soon in a world of his

own, playing games in his head with the wilderness of

reed beds and thickets. After about half a mile, the

pathway enters the marshes, and is carried through the

mudflats by a mile or more of duckboards, the reeds and

creeks encroaching on both sides. I suggested to Jim that

it might not be such a good idea if he was to step off

the boards, as this would lead to sudden death - or, at

least, very muddy trousers.

Taking the way of least resistance, the pathway veers

from side to side, so that every time I looked up the

tower of St Botolph was in a new position. We reached the

edge of the winding river again, and you could see at

once how the church and its two neighbouring houses are

on the end of a spit that sticks out into the marsh, St

Botolph itself on a little knoll at the end. A narrow

road runs along the spit, the only way to the church,

unless you have a boat; and even then, you could only

reach it at high tide, for at other times the river

drains to a silver thread, leaving a vast shimmering

expanse of grey mud to be picked over by wading birds. As

the river fills again, you are sometimes rewarded with

the sight of a marsh harrier, looming over small

creatures forced higher and drier by the rising water.

There is also the

other designated footpath from Snape to Iken, as I said

earlier. It cuts straight across the marshes, island

hopping across the muddy creeks. You could only do it at

low tide, and I think that in winter you could not do it

at all. When we reached the point where it was supposed

to join the path we were on, there were 20 metres or so

of shiny, lethal mud spreading where it was marked on the

map. We gazed at it. I imagined trying to cross it, and

thought to myself that I would get about three, perhaps

four metres. I simply wouldn't stand a chance. My

children would come at low tides, to see the bony,

skeletal hand protruding from the flat mud.

"Look!" their mother would say. "There's

Daddy!" I could tell that Malcolm was slightly

disconcerted to see a footpath marked on a map disappear

into grey nothingness. But then, he's from Derbyshire,

he's used to the permanence of stone, not coastlines that

melt with the seasons.

From here, the full drama of St Botolph catches your

breath. It is an ancient site. Well, that's easy to say,

of course, and true of many churches. But the site of St

Botolph really is ancient; you are looking at a place

where there has been a church for almost 1350 years. This

is almost certainly the spot where St Botolph came ashore

in AD 654, and founded his monastery. Some people will

claim the same honour for Boston in Lincolnshire, but

don't listen to them. This place was then Icanho, and St

Botolph and his monks set out across east Suffolk to

evangelise the pagans under the direction of Felix, first

Bishop of East Anglia, from his Cathedral at Dumnoc,

probably Walton Castle. Botolph died at or near Burgh,

where he was buried, probably in an attempt to exorcise

evil spirits. There is a case made for Burgh being the

setting for the dragon's lair in the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf,

probably written in Suffolk. The corpse was later

translated to Bury, where the monks knew a pilgrimage

opportunity when they saw one.

The church as we see it today is in three parts. The most

ancient bit is the nave, albeit restored. It dates from

before 1200. The chancel, like all others in England,

fell into disuse after the reformation. By the 18th

Century it was ruinous, and was demolished and rebuilt in

1853, and looks all of this date. Its 20th Century

sanctuary panelling is rather lovely. The tower is a

proud one of the mid-15th Century, very much in the

Suffolk style.

The church sits in its pretty churchyard across a private

road. This caused a considerable problem a few years ago,

as we shall see. The funny thing is that, although this

churchyard is surrounded on three sides by the marshes,

and the river spools around it like a cord of mercury,

the Alde still has six miles to go to reach the open sea

from here. A mile to the east, it reaches Aldeburgh. At

St Botolph's time this was the river mouth, but now the

river turns back inland, and heads south. As if this

wasn't contrary enough, it changes its name to the Ore.

After running parallel to the coast for three miles, it

reaches Orford, where it formed a natural harbour in

medieval times. But that, too, is now blocked, and the

river slinks westward of Havergate Island for another two

miles, coming out to sea at Shingle Street, just north of

the Deben estuary. This is a secret world, full of hidden

creeks and inlets. About twice a year, the local papers

report that coastguards have caught boats on this river

attempting to avoid duty by running tobacco or alcohol

ashore. The field immediately to the north of the

churchyard contained two Highland cattle, surprisingly.

Well, it certainly surprised me. It surprised seven year

old Jimmy even more, he thought they were yaks. The sky

had changed, a grey leaden colour seemed to have

condensed out of the icy blue. We stepped inside.

Low benches lined the north and south walls (today, these

have been replaced by ranks of angled 19th Century

benches, too mundane to be appropriate). To the west is

the great font, a good example of the 15th Century East

Anglian style. The angels that alternate with the

evangelistic symbols carry the Instruments of the

Passion. Beside it, another large object is hardly

discernible in the darkness. The walls to north and south

are blackened, calcified. The plaster has almost all

gone, and we are left with the rubble core, common to all

Suffolk churches, but normally hidden. What happened

here?

On the afternoon of the 4th July 1968, a gardener

clearing the churchyard lit a bonfire to burn rubbish.

Sparks from it caught the thatched roof of the nave, and

within minutes the whole place was alight. In this remote

spot there was no prospect of a speedy rescue, and the

church completely burned out, leaving a shell. It took

twenty years for repairs to be completed to the extent

you find them today, because a dispute over access meant

that materials had to be carried by hand from the road,

for vehicles were not allowed through into the

churchyard. First, the chancel was restored for use as

the parish church. An ill-fitting partition separated it

from the ruins. Later, a roof was put on the nave, and

the font (which had been removed to protect it from the

elements) was returned. But the interior of the nave

could not be protected, and for a decade or more it was

exposed to the Suffolk winters. And that is how you find

it today.

On my first visit, I noticed that the person before me in

the visitors' book had written a true taste of the

medieval! Poetic, but nonsense of course. In the

Middle Ages, this church would have been alive with light

and colour, of the flicker of candles and the smell of

incense. The walls would have been covered with brightly

coloured paintings, the bare shadow of one still

surviving behind a glass screen on the south wall today.

No, what we see today is more primal, ageless. The

architect of the restoration was Derek Woodley, also

responsible for the magnificent extension at Kesgrave All

Saints.

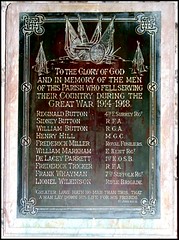

On the south wall is the war memorial. It is startling to

realise that this tiny hamlet lost ten men in the First

World War. There can barely be that many men living in

the whole parish today. With your back to the nave, the

chancel is of a homely, dull character. Johnson's

engraving of 1818 shows it in ruins. There is a picture

of this in the excellent guidebook and surreally another

picture shows the church after the fire, exactly the

opposite of Johnson's engraving, with the chancel whole,

but the nave in ruins. Only the tower stands in both, and

that was restored as part of the post-fire work. And

that's where we come to the most interesting thing of all

about Iken, for the large object by the font is nothing

other than part of a Saxon cross, discovered in the

superstructure of the tower when it was restored. It is

the bottom half of a cross that must have been about

three metres high, and the tenon that connected it to the

crossbar survives. It probably dates from the 9th

Century, and may have been raised on the site as a

commemoration when the community was re-established after

the Vikings had destroyed the original monastery. The

most interesting side faces the wall unfortunately, for a

curled dragon bites his own tail, but keeps his beady eye

on you.

Today, the tiny

congregation regularly use the chancel for services, but

the nave has become a haven for pilgrims, who make their

ecumenical way here in droves if the visitors book is

anything to go by. And I'm sorry to harp on about the

visitor's book, but another mistake made by people

leaving comments is to describe the cross as 'Celtic'.

This is, I think, a result of the way we have been

conditioned in the modern era to think of the Celts as

'New Age' artists and mystics, and the Saxons as dull,

plodding farmers. This is, of course, also nonsense, as a

sight of the Sutton Hoo treasure in the British Museum

will show immediately. Saxon art was gorgeous. It was

intimate and intricate, mysterious and beautiful. All too

soon, the Normans would come along with their big ideas

and corporate imagery, but it was the Saxons who built

the English imagination, and anyone who tells you that

the work here at Iken is Celtic should be disavowed of

that notion.

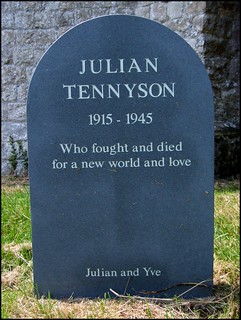

We wandered back outside to the east of the church, and

the memorial to the writer Julian Tennyson Who fought

and died for a new world and love. Tennyson's most

famous book is Suffolk Scene, a moving 1939

evocation of the county on the eve of the outbreak of

War. He was just 23 years old when he wrote it, and it is

a young man's book about an ancient county, one of the

most memorable books written about Suffolk in the 20th

Century. Sadly, Tennyson did not survive the war whose

storm clouds he had noticed, being killed in Burma

shortly before it ended. He was a grandson of the famous

19th Century poet, although that is one of the less

interesting things about him. I had been pleased to come

across this stone newly erected some fifteen years ago,

and once again it set me thinking about what Tennyson

would find different about Suffolk if he saw it today,

and what he would find unchanged. When he left to fight

he left a request that if he should die a memorial should

be placed in Iken churchyard. This request was not

fulfilled at the time, but it was carried out by his

daughter at the start of the current century when she

found reference to it in her father's papers after her

mother died. And Iken is a beautifully appropriate place

for him to be remembered, for to return here is to return

to where the story of Suffolk Christianity began. Across

the shifting, shimmering mudflats, the failing light

enfolds a beating heart, a pilgrim church where St

Botolph's journey has come full circle.

Simon

Knott, January 2020

Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England

Twitter.

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Churches of East

Anglia websites are

non-profit-making, in fact they

are run at a loss. But if you

enjoy using them and find them

useful, a small contribution

towards the costs of web space,

train fares and the like would be

most gratefully received. You can

donate via Paypal.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|