| |

|

|

|

Here we are in busy west

Ipswich. Ipswich can feel like a town of two

parts - the docks and the wide river split the

southern half of the town, and the great

Christchurch Park cuts in from the northern

suburbs right into the town centre. Older

townsfolk often identify themselves as either

from East or West, and it was unusual

historically for people to move from one side to

the other. The west side of town is poorer, with

acres of 19th Century terraces, and the more

recent additions of the challenging Whitton and

Whitehouse estates. Suffolk

doesn't have many 19th century churches - or, at

least, not many that aren't rebuilds of medieval

ones. All Saints, then, is something quite

unusual for Suffolk, not least because its red

brick style is most un-East Anglian, a

consequence of the architect being Samuel Wright

of Lancashire, who won the 1883 competition.

Perhaps he put in a speculatively high bid, and

was surprised to get the job. Still, the

octagonal tower is vaguely suggestive of Suffolk

round ones, and in any case it would be dull if

all churches were the same, especially 19th

Century ones. The parish was carved out of St

Matthew, closer into town.

All Saints sits on Chevallier Street, a

bottleneck on the Ipswich ring road, and so many

drivers every day get to have a really good look

at this church. There is a successful mixture of

styles, the Decorated details of the tower

providing the star of the show, and the

Perpendicular aisle windows with their great

arches are also not unpleasing, although perhaps

odd in that their 'wall of glass' 15th Century

style is contradicted by the rather forbidding

and severe red brick expanse and high roof. The

great east (Dec-style) and west (Perp-style)

windows are rather more successful.

|

Stepping inside, the view eastwards

through the brick arcades and plain windows of the nave

is impressive. All materials, so it is claimed, were

produced in the parish. Here we are seeing the language

of Early English fluting, for the pillars of the arcades

seem impossibly slight to support the great weight above

us. In fact, it is a cunning trick, for the arcade is

actually constructed of cast iron pillars concealed by

brick dressing. It is all very well done. There is a

sense of emptiness in the nave which contrasts excitingly

with the mystical gloom of the chancel beyond the rood

screen.

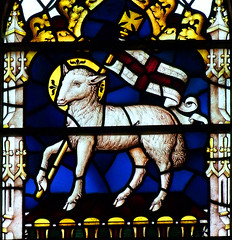

| The sanctuary is full of

serious colour. This building was designed for

Tractarian incense-led worship. The five-light

east window of Christ in Majesty flanked by St

Edmund, the Blessed Virgin, St John and St Felix

is credited by Pevsner's revising editor to

'Campbell of London', but it is certainly the

work of Horace Nicholson (thank you to Aidan

McRae Thomson for pointing this out to me).

Whoever Campbell may have been, perhaps Nicholson

was working for him. The window dates from 1938,

and is in fact the earliest glass here. Perhaps

the windows were clear before this. The other two

windows are both in the north aisle. That at the

east end of 1950,depicting St Edmund and St

Felix, is by Horace Nicholson's son, AK

Nicholson. The window at the west end, of 1943,

depicts Christ and the children, and is by far

the best window in the church. Its artist is

unrecorded, but perhaps it is also by AK

Nicholson. When the

church opened in 1884, a young clergyman from a

small village in Kent was appointed as its first

minister, a 'curate-in-charge'. His name was

Richard Munro Cautley, and his young son Henry

would grow up to not only be diocesan architect,

but the greatest historian of East Anglia's

churches. He designed three Ipswich churches, St

Augustine, All Hallows and St Andrew, as well as

other Ipswich buildings including Ipswich County

Library, and the Walk shopping precinct which he

designed with his partner Leslie Barefoot. The

young Cautley learned the aesthetics and

principles of High Anglican worship, and these

infuse just about everything he ever built. He

was only ever at home in the idiom of the late

Middle Ages, and it is a tribute to the work of

Samuel Wright of Lancashire that Cautley learned

it first here.

|

|

|

|

|

|