| |

|

|

On January 8th, 1297, a

royal wedding took place in Ipswich. Princess

Elizabeth, daughter of King Edward I, married the

Count of Holland. Fitch, in his annals, records

that Edward I stayed in the town for the ceremony

with 'a splendid court', and that the three

minstrels were paid 50s each for their

services.The wedding took place, not in any of

the parish churches of the town, but in one of

England's major shrines of Marian pilgrimage; a

shrine to which we may presume Edward I had a

special devotion. This was the Shrine of Our Lady

of Grace, also referred to in contemporary

records as Our Lady of Ipswich.

This wedding is just the earliest record we have

of a royal occasion at the shrine. Thereafter, a

succession of visitors come here on pilgrimage,

culminating in the early 16th century, when the

pilgrimage cult was at its height. Between 1517

and 1522, both Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon

made journeys to the shrine, set beside the

Westgate in the parish of St Matthew. Other

visitors included the local dignitary Cardinal

Wolsey, and the future saint Thomas More.

It is hard for us to understand today the part

that Mary played in the medieval economy of

grace. Contrary to popular belief, there is

considerable (and growing) evidence that the

people of rural medieval England had an

articulate and sophisticated understanding of the

nature and purposes of intercessionary prayer.

Although there may have been abuses, when people,

in some sense, offered 'worship' to images of the

Madonna, this was not a general practice, or even

a common one. Mary was seen as a focus of prayer;

contemporary images of medieval people frequently

show them carrying their rosary beads. |

To have some

understanding of the role of Our Lady in the hearts and

minds of medieval Suffolkers, we need to look at the

church in southern Europe today. The spectacular

processions, the colourful images, the celebrations and

devotions would all have been a part of medieval Suffolk

life. Fundamentally, the people of medieval Suffolk, in

all their daily trials and tribulations, in the midst of

their suffering and expectation of an early death, saw

Mary as being on their side.

A surprising amount of evidence of the medieval affection

for Mary survives in Suffolk, considering how this cult

outraged the reformers of the 1540s, and was attacked by

Puritans and Anglicans throughout the 17th and 18th

centuries. A brief survey of churches with entries on

this site will find the rosary dedication at the base of

the tower at Helmingham, the Hail Mary monograms on each

side of the tower at Stonham Parva, the so-called Doom

painting at Cowlinge, where Mary tips the scales in

favour of sinners, and many more. About half of the

medieval churches in Suffolk are dedicated to St Mary.

Although Nicholas Orme's seminal survey English

Church Dedications has shown us that many current

Anglican dedications are well-meaning 18th century

inventions, will evidence proves that many of the Suffolk

dedications to Mary are correct; except that the

dedication would usually be to a Marian solemnity or

devotion, most commonly the Assumption. This dedication

has been restored correctly by the Anglo-catholics at

Ufford. Of the churches not dedicated to Mary, all would

have contained a Marian shrine.

These shrines were most commonly at the east end of the

south aisle, and were often restored by the Victorians as

a 'lady chapel'. Some of these shrines became famous as a

result of reports of their efficacy. Some became so

popular that they were translated to buildings of their

own. This is probably how the shrine of Our Lady of Grace

came to be, although its actual origins are lost in the

mists of time.

There were four churches within a stones throw of the

shrine, of which two, St Mary Elms and St Matthew,

survive today. Edward I's visit to Ipswich came two

hundred years after the founding of the greatest English

Marian shrine at Walsingham, about sixty miles from

Ipswich. We may assume that the fame of Ipswich grew in a

similar way to that of Walsingham.There were other major

shrines in Eastern England at Kings Lynn, Ely and

Lincoln; in Suffolk, we know that pilgrimages were made

to Bury, Woolpit and Sudbury, amongst others.

The fame and influence of the Ipswich shrine reached its

peak in the early years of the 16th Century, after an

incident known as the Miracle of the Maid of Ipswich.

This occured in 1516 and was held in renown all over

England in the few short years left before the

Reformation intervened. The popularity of the Miracle, in

which Joan, a young Ipswich girl, has a near-death

encounter and experiences visions of the Virgin Mary, was

widely used by the Catholic Church as a buttress against

the murmurings of reformers.

The late Dr John Blatchly, in his book The Miracles

of Lady Lane showed convincingly that the font in

nearby St Matthew's church was paid for by the Rector

John Bailey to celebrate the Miracle of the Maid of

Ipswich, and the visit to Ipswich of Henry VIII and

Katherine of Aragon soon afterwards. The panels of the

font depict events in the devotional story of Mary,

mother of Jesus. These five reliefs, and a sixth of the

Baptism of Christ, are amazing art objects. They show the

Annunciation to the Blessed Virgin with Gabriel unfurling

a banner from which a dove emerges to whisper in Mary's

ear; The Adoration of the Magi, with the wise men pulling

a blanket away from the Blessed Virgin and child as if to

symbolise their revelation to the world; the Assumption

of the Blessed Virgin, with Mary radiating glory in a

mandala, which four angels use to convey her up to heaven

in bodily form; the Coronation of the Queen of Heaven,

the crowned figures of God the Father and God the Son

placing a crown on the Blessed Virgin's head while the

Dove of the Holy Spirit races down directly above her;

and the Mother of God Enthroned, the crowned figure of

the Blessed Virgin sitting on the left of and looking at

(and thus paying homage to) her crowned son on the right,

who is holding an orb.

Dr Blatchly thought

that the panel of the Mother of God Enthroned was a

representation of Katherine of Aragon and her husband

Henry VIII, which I think a little unlikely, although of

course it could be both, one representing the other.

Remarkably, two of the four figures around the base are

probably intended as Joan, the Maid of Ipswich, and John

Bailey the Rector himself.

In The Miracles of Lady Lane, which Dr Blatchly

co-authored with the historian Diarmaid MacCulloch, there

is a fascinating if somewhat convoluted account of the

battles between Bailey and Cardinal Wolsey, who was

trying to consolidate his power in Ipswich by taking over

the Shrine of Our Lady of Ipswich, which was in the

parish of St Matthew. It is the kind of thing Trollope

would have written about if he had been around in the

16th Century. Bailey's celebration of the Miracle was

partly a way of competing with Wolsey for fame and

influence, but Bailey's death in 1525 left the way open

for the Cardinal, who in his turn would completely

over-reach himself and fall in his own way.

The book is memorable as a picture of the incredible

religious fervour in Ipswich in the early years of the

16th Century, enthusiasms that would spill over into

passion and violence. Blatchly notes that the sequence of

at least some of the Marian images on the font was

replicated by a sequence of inns down the mile of

Ipswich's main street, now Carr Street, Tavern Street and

Westgate Street, which led to the shrine. One of the

inns, the Salutation (ie, Annunciation) at the start of

Carr Street, survives in business under the same name to

this day. But in time of course Ipswich would become

well-known as the most puritan of towns in the most

puritan of England's regions.

The focus of any Marian shrine would be the statue of

Mary, most often with the infant Christ on her knee. When

the reformers of the 16th century set out to break the

hold of the Church on the imagination of the people,

statues of Mary and the saints were the first things to

go. Poor William Dowsing, who inspected Suffolk churches

for 'superstitious imagery' 100 years later in 1644, is

often blamed for the destruction of these statues; but

his meticulous journals do not suggest that a single one

of them had survived to his time.

The shrines were suppressed in the spring of 1538, and

Sir Charles Wriothesley, in his Chronicle, writes that

in the moneth of July, the images of Our Lady of

Wallsingham and Ipswich were brought up to London with

all the jewelles that hang about them, at the Kinge's

commandment, and divers other images... because the

people should use noe more idolatrye unto them, and they

were burnt at Chelsey by my Lord Privy Seal. Wodderspoon,

in his memorials, records that (Thomas) Cromwell...

caused this image of Our Lady to be pulled down from her

niche, and after despoiling the effigy of its rich

habilements and jewels... it was conveyed to London and

destroyed. John Weever, writing a century after the

event, reports that all the notable images, as the

images of Our Lady of Walsingham, Ipswich, Worcester, the

Lady of Wilsdon, the rood of grace of Our Lady of Boxley,

and the image of the rood of St Saviour at Bermondsey,

were brought up to London and burnt at Chelsey, at the

commandment of the aforesaid Cromwell.

This is a particularly folkloric account, since we know

that several of the images mentioned were not burnt at

Chelsea, but were destroyed elsewhere. There is no

evidence that any of the surviving reports are by

eye-witnesses, and although there are many other reports

of the burning, all are circumstantial, and most seem to

be based on Wriothesley's Chronicle. Stanley Smith, in

his majestic The Madonna of Ipswich, concludes

that the conflagration took place at Thomas Cromwell's

house at Chelsea on 26th September 1538, under the orders

of Bishop Latimer, and before the eyes of the Lord Privy

Seal. The Ipswich statue certainly made it to Chelsea.

Thomas Cromwell's steward wrote to him that he had

received it, with 'nothing about her but two half shoes

of silver'. This report will be crucial, as our story

develops.

In general, where a Marian shrine was not in a parish

church, the building that had housed it did not survive

for much longer. During the 17th and 18th centuries,

several legal documents, especially those dealing with

the transfer of ownership of land, make reference to the

remains of the Shrine of Our Lady of Grace. John Waple

bought land 'at the south end of the La. chapel wall' in

1566. In 1650, Edward Bartle was granted 'land on which

once stood a chapel, called the Lady of Grace chapel,

land whereon a stable is now built'. In 1761, a Mr Grove

visiting from Richmond reports that 'there is scarce one

stone left upon another'. Of course, the terrible irony

of this is that we can use these land documents to

pinpoint exactly where the shrine of Our Lady of Grace

was. Another advantage to locating the shrine is that the

general layout of streets in the centre of Ipswich has

changed little since Saxon times, despite the best

efforts of Sixties town planners.

The shrine, then, was just outside the west gate of the

town wall. This was demolished in 1782, but photographs

exist of a rather fanciful reconstruction put up for the

Jubilee celebrations of 1887. The gate stood in Westgate

Street, just beyond where a footpath now cuts through to

the Wolsey Theatre. The shrine stood on the next corner,

where a Sixties block once housed a Tesco supermarket,

but now contains a number of dismal discount stores. The

narrow road to the left here is called Lady Lane, and was

certainly called that in 1761, although I cannot discover

if this name was contemporary with the shrine.

We can also form some idea of what the shrine looked

like. Stanley Smith records surviving wills which

bequeathed items, including, in 1498, a porch and glass

for the east and west windows. There was almost certainly

a burial ground; this is referred to in a land transfer

document and a will, and human remains were found on the

site in the early 20th century. When Tesco was built in

1964, chunks of church masonry were discovered on the

site; however, we should remember that, after the

Reformation, rubble from many demolished religious

buildings (of which Ipswich had plenty) were used in the

construction of other buildings.

What appears to be a pilgrim's token was also found near

the site; but, as Stanley Smith points out, pilgrim's

tokens from many shrines have been found around

Walsingham, and there is no reason to believe that this

particular medal originally came from Ipswich.

In Lady Lane itself, a small statue was put up in the

early 1990s as a memorial to the shrine; it replaced a

1960s plaque.

This statue repays

close inspection, because the story gets slightly more

exciting at this point. Despite the conflagration at

Chelsea in 1538, there is some evidence that the statue

of Our Lady of Grace survived, and still exists today;

and that this memorial statue is a true copy of it. In

the Italian city of Nettuno, most famous perhaps for its

harbour of Anzio, there is a shrine to Our Lady of Grace.

There is a story that the image there was brought to

Nettuno from England during the Jubilee year of 1550.

There is some evidence in the town archives to support

this. And the town archives also mention Ipswich.

It wouldn't be that improbable. Western mainland Europe

is full of statues and sculptures produced in England

during the 12th and 13th centuries. Many of them must

have been exported at the time; Nottingham alabaster

work, for instance, was greatly prized throughout Europe.

But much probably went abroad at the time of the

Reformation. It must be remembered that the Reformation

in England placed quite a low priority on the new

teachings of Luther and Calvin; they were the job of the

theologians. But the state, which enforced the

Reformation in England, was more concerned with wresting

political power from the church, and enriching itself on

the wealth of the churches, shrines and monasteries. It

achieved both of these goals extremely successfully; the

first is shown by the fact that there was no religious

war in this country, and the second by the fact that the

Tudor royal family amassed riches beyond its wildest

dreams, much of it to be squandered by Elizabeth I and

James I on high living and piratical expeditions to the

'New World'.

There was no evangelical agenda on behalf of the English

state as there would be 100 years later under Oliver

Cromwell. It is hard to imagine William Dowsing selling

images abroad, but there is a great amount of

circumstantial evidence that the cronies of Thomas

Cromwell and Thomas Cranmer in the 1530s and 1540s did

exactly this. It was a pragmatic approach; they wanted

rid of images, and they wanted to accrue the wealth of

the church. That said, the Nettuno legend records that

the statue was rescued from the flames by secretly

Catholic sailors, who spirited it safely abroad. I think

the sales story outlined above is more likely, though.

The Nettuno image was identified as English as early as

1938 by an historian of 13th century iconography, Martin

Gillett. He felt that considerable changes had been made

to it; Mary's head had been replaced, and the posture of

the infant Christ changed. The throne (no longer in

existence) was a 19th century replacement. But the folds

in the material, the features of the Christ child, the

position of the infant on the right knee rather than the

left, and the carving style, all strongly suggest an

English origin. And then war intervened. Anzio and

Nettuno were the site of some of the fiercest fighting

during the Allied landings in Italy, and the statue was

seriously damaged. During its restoration in 1959, an

antiquated English inscription was found below the

Madonna's right foot: IU? ARET GRATIOSUS (thou art

gracious).

This supports, as Stanley

Smith says, the local dedication of Madonna della

Grazie. The inscription had been overwritten

SANCTA MARIA, ORA PRO NOBIS, probably in the late

16th century.

Interestingly, no other major English Marian

shrine was dedicated to Our Lady of Grace. Even

more striking, when Martin Gillett first examined

the statue in 1938, it was wearing two half shoes

made of English silver, just like those described

by Thomas Cromwell's steward 400 years before.

Obviously, there is a great yearning for it to be

true. I think, on balance, that the statue at

Nettuno probably is the statue of Our

Lady of Ipswich. Other people seem certain of the

fact; hence the replica in Lady Lane.

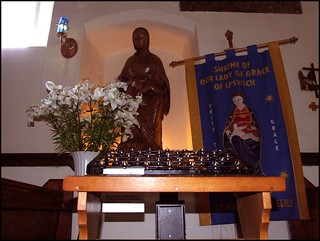

The Guild of Our Lady of Ipswich is an ecumenical

group formed in the 1980s by people from the

Catholic church of St Pancras and the Anglican

church of St Mary Elms. They have re-established

Marian shrines in both these churches, and meet

monthly. They have also re-established the

procession which Cardinal Wolsey instituted from

St Peter (by his college) to the site of the

shrine. They make this walk every year on the

date of its predecessor, 7th September. Even more

excitingly, they have also placed a replica of

the Nettuno statue in the church at St Mary Elms.

It was dedicated with great ecumenical ceremony

under the watchful eye of the Guild in September

2002. |

|

|

Simon

Knott, 1999, updated November 2016

|

|

|