| |

|

|

|

Coming back to Ixworth

after almost twenty years away, I found that I

couldn't remember where the church was. Being too

lazy to get out my map, and not stupid enough to

use a satnav, I cycled up the long hill of that

remarkably good high street until I reached the

fire station at the top, and then I was back in

open country. Finally checking the map, I found

that the church was at the bottom of the hill.

Still, it didn't take long to get back there.

Ixworth is one of those small towns, or large

villages, that Suffolk seems to do so well. The

Bury St Edmunds to Diss and Stowmarket to

Thetford roads cross here, but both are now

carried past the village on bypasses, and so

Ixworth has the pleasant air of a relatively

remote and self-sufficient place, with a shop, a

post-office, a couple of decent pubs, and that

pre-requisite of modern rural civilisation, a

ladies' hairdresser. There's a super little water

mill on the road to Pakenham, actually in

Pakenham parish but closer to here. Ixworth is

not to be confused with Ixworth Thorpe, a tiny

hamlet a mile or two to the north, with a

stunning little thatched church, and especially

not with Ickworth, home of the Marquis of

Bristol, some ten miles to the south-west.

|

As I say, the church is immediately

beside the high street, but as it is concealed from it by

a row of shops and houses I felt vindicated for cycling

past it without noticing. A short driveway leads into a

small churchyard, out of which rises a big church, at

first sight all built on the eve of the Reformation. This

is pretty much the case, since the late 15th and early

16th century replaced everything except the porch and the

chancel, and there are even contemporary dates for the

completion of the tower. All that remained to be done

happened in that other great age of faith, the late 19th

century, when they replaced the chancel. All pieces of

the ensemble are fairly typical of their dates.

Look west of the church, and you can see the site of the

former Ixworth Priory. Most of this has now gone, but the

vaulted undercroft has been retained as part of the

current house on the site. There are more ruins visible

from the High Street further west.

You step into the feel of a thoroughly urban church, as

at Yoxford. This is partly a result of the rather

mediocre 1854 restoration, early for the century and

before people cared too much about rescuing old things,

hence the sombre replacement benches. But it is also to

do with the sheer size of St Mary, and perhaps that

serious east window too. The aisles are wide enough for

the nave to feel as broad as it is long. Towards the

west, the space beneath the tower has been converted into

a meeting room, all finished rather well in the early

1980s manner. Sam Mortlock tells us about something

rather fascinating we would be able to see inside the

meeting room if it wasn't locked. Several of the

dedicatory tiles that were set in the buttresses of the

newly-finished tower in the 16th century have been reset

here.

One of them is to a local man called Thome Vyal. I could

just make it out through the glass door. Mortlock tells

us that his will was proved in 1472, and he gave four

pounds to the steeple. The interesting thing about it is

that we know Vyal was a carpenter, so he probably worked

in this church, where no woodwork of the period survives,

but perhaps also at nearby Ixworth Thorpe, where much

does. Additionally, many of the churches round about here

are famous for their bench ends. Perhaps this suggests

that Ixworth might once also have had wonderful carvings

before the Victorian restoration.

The sombreness of the nave is barely enlightened by the

clerestory, and isn't helped by several heavy memorials

around the north doorway. But the lady chapel at the end

of the north aisle is rather sweet. In medieval times, it

was the chapel of the guild of St James, says Mortlock.

In any case, there is plenty of evidence of the busy life

of the parish, so the gloom doesn't weigh you down too

much.

The base of the roodscreen survives, and you step up

through it into the 19th century chancel. Now, this is

really serious - the great east window positively frowns

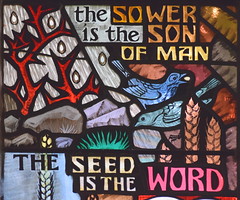

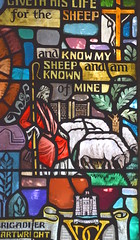

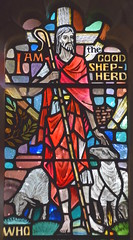

on you. But all this lightened by a gorgeous window of

1966 by Herbert Powell depicting the parables of the

Sower and the Good Shepherd, all very much in the

contemporary style of the day. There would be a loss of

nerve over the following half century from which stained

glass design is only now recovering from.

The east window is an early work by

the O'Connor Brothers of 1854, and is really rather

magnificent, showing two angels flanking the Good

Samaritan at the bottom, and a Crucifixion flanked by the

Resurrection and the Ascension. Clearly, the window is

before George Taylor took over the firm and rebuilt its

fortunes, and their earlier style is more harmonious than

it would become by the 1870s. Up in the sanctuary, the

Victorians reset the perky tomb of Richard Coddington.

Brasses of Coddington and his wife are set within a

semi-circular relief, and the tomb chest beneath glows

with heraldry.

Coddington was not from Suffolk at all, and could never

have expected to end up buried here. However, when the

monasteries were suppressed in the 1530s, Henry VIII

offered the estate and lands of Ixworth Priory to

Coddington in exchange for the village he owned near

Ewell in Surrey. This was good business for Coddington,

but unfortunate for the villagers of the little

settlement of Cuddington, because Henry had their houses

and church erased from the map.

| In their place, he built

the massive pile of Nonesuch Palace, the largest,

grandest and most highly decorated single

construction in England during the course of the

16th century. It was furnished with all the great

riches that continental Europe had to offer. It

was surrounded by an amazing park, woodlands and

rides. I suppose that it is good to know that the

irreplaceable treasures of the English medieval

church weren't all frittered away on pointless

and fruitless sieges of French coastal towns. Nonesuch Palace no longer exists.

When the English royal family could no longer

keep itself in the manner to which it had become

accustomed, the house was demolished for building

materials. This seems to have taken a

considerable time, for destruction began in the

1680s, but at least one of the towers was still

standing in the early 18th century. Oliver

Cromwell himself had overseen the selling off of

the contents during the Commonwealth, and his

parliament had ordered the cutting down of most

of the trees for shipbuilding. Hardly a memory

survives today. But Richard Coddington lies here,

probably still feeling quietly pleased with

himself.

|

|

|

|

|

|