| |

|

|

|

I’m not a great reader

of newspapers, but if ever I buy one of

those big weekend ones, they always seem

to contain a horror story about someone

who moves from the noise and dirt of

London or Birmingham to a rural idyll,

only to find themselves shunned as an

outsider by the natives. Not only does

the village post office not sell

carpaccio, they get stonewalled in the

village pub. It’s not a price worth

paying for decent schools. Within six

months, they’re packing the Range

Rover and hightailing it back to the big

city, relieved to return to civilisation. Some English

counties do not accept incomers easily. I

think Suffolk does, partly because the

people are so easy-going. Mind you, this

may change as more and more villages,

especially on the coast, fall victim to

second-home owners. New arrivals add to

the economy and cultural life of a

village, but nobody wants to live beside

an empty cottage for ten months of the

year. I am not from Suffolk originally,

but certainly feel as if I belong here.

It was one of the proudest moments of my

life when the local radio station

described me as an ambassador for the

county. But when I’m out on the

western border, I get a yearning that

reaches me nowhere else; the call for

home. I am Cambridgeshire-born and bred;

for generations, my family were fen men

and women, outlaws and vagabonds before

the great draining, survivors and

schemers after it. Culturally and

politically, the Fens have always been a

place apart, the South Armagh of England.

|

The strange landscape of my

ancestors haunts me now. I grew up in the bustle

of the city of Cambridge, but my thoughts still

turn north of it to the flat land. And south-east

of the Fens, the graveyards of the

Cambridgeshire/Suffolk border are full of my

mother’s maiden name.

Kentford is about as close

to Cambridgeshire as you can get; to the north of

the churchyard, the busy A14 marks the border.

Kennett station, 300 metres away, is in

Cambridgeshire. Often along this border,

adjoining parish centres merge, as if ignoring

the vagaries of Saxon bureaucrats; in their

names, Kentford and Kennett reveal themselves as

two parts of the same whole.

As with all the Newmarket

hinterland, Kentford looks to Cambridge more than

it does to Ipswich and Norwich. For two

centuries, Cambridge was the poor cousin of the

three, but the high-tech developments of the last

twenty years have completely reversed this, and

houses around here cost twice as much as they do

in east Suffolk or south Norfolk. More than that,

this area is wooded, and hilly; a landscape that

seems to stop at the border. Basically, Suffolk

is prettier than Cambridgeshire.

At one time, Kentford high

street was the main road from Cambridge to

Ipswich, Norwich and the seaside. If you grew up

in the sixties and seventies like I did, and

lived so far from the sea, you’ll know that

you didn’t get to see it very often. I

remember summer mornings, still cold from the

hour, the excited coach escaping the sleepy city,

the whole pleasure of the day ahead contained in

it. I remember Kentford as the first hill we

reached, as if entering a foreign country.

You’d know for certain now what a wonderful

day it was going to be. Perhaps because of this,

the sun is shining whenever I visit Kentford, as

if a powerful memory lingers on, like a charge or

a charm. Perhaps the sun always shines in

Kentford.

Today, the village is

completely bypassed, but St Mary still sits at

the top of the hill in the little graveyard.

There is a pub a bit further east, and a shop

along the road to Moulton. With the

station and A14 nearby, it’s no surprise

that this is increasingly a commuter village, but

it still seems to have a considerable life of its

own. I’m very fond of it; today, Kentford is

often still the start of a journey for me, if I

take my bike on the train to Kennett, and spend

the long day cycling through the lanes back to

the coast. There is still an excitement.

St Mary is not a big

church, and its tight hilltop graveyard means

that you could easily miss it if you were driving

through. Best not to drive; medieval Suffolk was

not designed for cars. Just inside the church

gate, there is a fine early 18th century grave,

and in general a genealogist would spend a happy

hour here. The building is largely 14th century;

its rather ideosyncratic appearance is a result

of a considerable 18th century renovation. It has

been left a largely lovely building, attractive

in an otherwise fairly workmanlike village.

The church is ordinarily

kept locked, and the key is at the Cock public

house. So, this is a church to visit in pub

opening hours. And, since parking is near

impossible on the village street, you can park at

the pub, refresh yourself with a pint, and then

wander over to the church. You let yourself into

a delightfully atmospheric space, a brick floor

with simple, rural furnishings, a seemly High

Church chancel and a silence brewed God knows

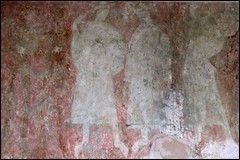

how long. Directly opposite is the great

treasure of the church, one of the few surviving

medieval wall-paintings in East Anglia of the

Three Living and the Three Dead. Three hunting

courtiers encounter a trio of skeletons in the

woods; As I am so you shall be, observes

the first. Rich and poor come to the same end,

points out the second. Just in case there is any

doubt, no one escapes, declaims the

third. This church used to have other wall

paintings, but all have now been plastered over,

awaiting a kinder, gentler age when money is

available for the restoration of such things.

Another

interesting feature of the church is the good

range of early 20th Century glass, all of it

unsigned, unfortunately. The most striking is the

east window of about 1920, a memorial to Henry

Otto Lord. Henry Lord was a lieutenant in the

26th Manchester Regiment amd, as the window

points out, a Scholar of Christ's College,

Cambridge. Born on the 29th May 1896, he was the

eldest son of Henry and Frieda Lord of Kentford

Lodge, and was killed on the opening day of the

Battle of the Somme 1st Juy 1916, a few weeks

after his 20th birthday. The boy is depicted in

shining armour kneeling before the cross, while

other panels of the window depict the

Resurrection, the Ascension, and Christ in

Majesty. It is extraordinary to think that it was

produced less than a century ago.

Perhaps

the best of the glass is in the chancel north and

south windows. A stunning roundel of a bee

collecting pollen surmounts the monogram GG. Who

was that, I wonder? A delightful panel opposite

depicts an icon of the Blessed Virgin and child,

with a verse from the Magnificat. It is all

utterly enchanting, and perhaps makes what I am

about to tell you next all the more concerning.

Shortly

after the first entry for this church appeared in

2002, I received an e-mail from the parish clerk.

I had been unable to get inside, and bemoaned

this fact. She told me, rather unnervingly, that Kentford

church had almost been lost to us. It had sunk

about as low as it is possible to go without

actually disappearing from sight; the last PCC

had given up eight years previously, and the

congregation had fallen to zero. The church was

closed for a year, pending the possibility of

redundancy. However, an energetic new Rector had

arrived in the Benefice, and rapidly increased

congregation numbers in each of his five

parishes.

So, the garden of faith was

flowering again at Kentford, but the chance of

redundancy still existed. The people in the

parish were working hard to make survival a

proposition. By 2002 they were up to two services

a month, which I see they are still maintaining

in 2013, and the congregation was up to about

twenty people. The locals were busy organising

fund-raising events, tracking down the old parish

bank accounts, and generally giving this pretty

little church a fighting chance.

| It is easy to say that the

Church is the people, not the building,

but St Mary is a good example that a

church building is the engine house of a

gathered faith - it would be wonderful to

see Kentford church move towards a

position where it was open during the

day, and people could be encouraged to

stop a while, for rest and reflection.

Churches where this happens find it can

be a way to grow their congregations;

after all, some people may come back on

Sunday. And, according to ChurchWatch, a

locked church is twice as likely to be

broken into as an unlocked one, twice as

likely to be vandalised, and even

slightly more likely to have something

stolen from it. But there’s

more to it than that, of course. A locked

church is a dead church, both spiritually

and culturally. People who no longer have

the touchstone of an open church have

their faith privatised, however strong it

is. Those without faith have no access to

it. At Kentford, there is a chance for a

Church to pull back from the brink, and

for a building to play its part in being

the body of Christ to the people of God.

|

|

|

|

|

|