| |

|

|

|

This is a fascinating and

spectacular church, probably the least

visited of Suffolk's great municipal

Perpendicular churches, despite being

only ten miles or so north of Southwold

and Blythburgh,

with which it forms a group. It is one of

the county's biggest churches; and yet,

of the other big medieval ones, only Hadleigh

has suffered a more drastic 19th century

makeover. But there is much of interest

here, and a visit is worthwhile for all

sorts of reasons. Lowestoft's only major

town centre church is the beautiful Our

Lady, Star of the Sea.

St Margaret stands on a hill top to the

west, which may seem strange, but the

same was true once of the church at Aldeburgh,

although the sea has cut in there to make

the church appear more central. In both

cases, the towers are able to act as a

landmark to ships at sea. All along this

coast, the sea has claimed churches in

the last 600 years; six at Dunwich,

and others at Easton

Bavents, Sizewell, Gedgrave

and so on. At Pakefield,

the church was half a mile from the sea

as recently as 1900; but today, the waves

lap at the foot of its churchyard. In

another 50 years or so, Pakefield

church will be gone, and so will Covehithe.

But not St Margaret. The unpredictable

nature of the tides has meant that the

sea at Lowestoft has actually gone out;

the industrial estate on the Denes below

the High Street was under water 500 years

ago (many would wish it a return to that

state). |

With the town below it, and no major

road leading past it, St Margaret is not a church

to come across by accident. It is surrounded by a

large modern housing estate, but the great size

of the churchyard keeps it at arms length. I have

never seen so many gravestones in a churchyard

anywhere else in East Anglia. They cluster and

lean together like a Jewish cemetery.

Like

most great Suffolk churches, St Margaret was

rebuilt several times during the Middle Ages. The

14th century gave it a grand tower, but this was

completely dwarfed by the massive nave, aisles and chancel built in

the 15th century. The Reformation intervened

before the tower could be rebuilt to scale, and

so it appears curiously mean beside the body of

the church against it, exactly the same situation

as at Blythburgh, with

which this church has many similarities. The 15th

century builders put an elegant lead and timber

spire on the tower, possibly as a temporary

measure, but it stands there to this day.

| The porch is one of

Suffolk's largest, a double-story affair

as at Blythburgh.

The upper storey may have been an

anchorites' cell, an to this day is

referred to as 'the Maids' Chamber', and

their names are recorded in folklore as

Elizabeth and Katherine. In the vaulting

of the lower stage is a magnificent boss

depicting the medieval image of the Holy

Trinity. A seated God the Father golds

his crucified Son while the dove of the

Holy Sp[irit descends from above. A

sign says Welcome - but the door

is ordinarily padlocked, because we are

in Lowestoft, and that is the way the

parishes of Lowestoft keep their

churches. However, the people here are

very happy to open up. If they let you

in, it will be through the Priest's door,

so your first sight of St Margaret will

be the huge Victorianised chancel, and

the vastness of the nave opening out

beyond it. There is no chancel arch; as

at Blythburgh

and Needham

Market, this is intended

as a great Perpendicular space.

|

|

|

You step down into the wide nave,

filled with turn of the century benches. At the

far west is the gorgeous font cover, the work of Ninian Comper, much more

elegant than his enthusastic work at nearby Lound. Behind it

in the west wall is the rather alarming door to

England's biggest banner stave locker. It is

based on the one at Barnby;

unfortunately, the original is only about 4 feet

high, and this has been made to scale at three

times the size. Given that the Barnby one was

unfinished, is remarkable for its existence

rather than its style, and was hanging upside

down at the time it was copied, it seems a

curious thing to have done.

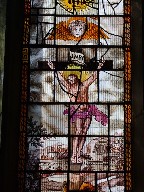

The great east window is filled with

1890s glass, which isn't terrible; but what it

replaced was rather more interesting. In 1819,

the window was filled with glass by the Regency

artist Robert Allen. It is his only known

glasswork, and is terribly rare. Fortunately,

much of it was reset in the south chancel, where

you can see it to this day.It seems curiously

primitive and dated, a fascinating example of

vernacular window painting on the eve of the 19th

century revival. Interspersed with it is a

collection of interesting continental glass,

probably collected and set here by Samuel

Yarrington.

The

gorgeous glass in the west end and north aisle

came from the demolished church of St Peter. It has

lost some of its drama by being moved into such a

large space, but is still excellent. It is by

Christopher Whall.

I

also love the memorial window to Lowestoft's

fishermen drowned at sea; it shows one of their

patrons, St Andrew.

There

are a great many memorials of interest, including

a large number of ledger stones. One of these is

to the 17th century puritan Samuel Pacy, who, as Mortlock reminds

us, was partly responsible for the great witch

hunt hysteria in Suffolk during the 1660s. He

himself accused two local widows, Rose Cullender

and Amy Drury, who were either harmless medicine

women or Catholics, or probably both, of

bewitching his daughters. They were hung at Bury

St Edmunds in 1664, along with 38 other innocent

women and children. It always seems odd to me

that the 19th Century evangelical protestants of

Bury erected a memorial beside St James to the 17

Suffolkers murdered for heresy during the reign

of Mary I in the 1550s, but this equally foulact

by their puritan forbears has been forgotten.

| Another most curious

memorial is on a brass plaque on the

chancel arch; it says To the Glory of

God and in Thanksgiving for the Safe

keeping of the Church and Congregation in

the Violent Thunderstorm of Sunday Aug

21st 1921. The

roof is rebuilt, so we are deprived of

seeing one like that at Blythburgh, which

it probably was once. It has been painted

and guilded, and I wonder if this was

also the work of Comper. The nave is full

of inlays for brasses, most of which,

sadly, have disappeared over the years. A

few remain. The view to the east, with

nothing breaking the roofline until the

east window, is magnificent. There is a

reconstruction of a parclose screen and

loft in the north aisle, which was

intended to continue across the church.

If this had happened, it would have been

a better and more impressive

reconstruction than that at Rattlesden.

Finally, this

church has one of Suffolk's few medieval

brass lecterns; one of the few survivals

here, apart from the font, of the

Catholic life and liturgy of this place

before the Reformation.

|

|

|

|

|

|