| |

|

|

|

Here we are where High

Suffolk comes down to meet the start of

the Gipping Valley, an area which has

been a meeting place for two thousand

years or more, an area of moots and

markets, of travellers and traders.

Around the town of Stowmarket, the

placenames reveal the pattern of the

past, and such a one is Old Newton. The

name is a pleasing contradiction, and the

parish is beautiful away from the busy

Stowmarket to Rickinghall Road. The best

view of the church is from the top the

hill on the back lane from Stowupland. I

came here in the early spring, when the

whole valley was still wearing its winter

clothes, but the sunshine promised much.

Closer to, the buds were on the trees,

and the green barley shoots spread across

the valley like a frost. I felt pleased

to have seen it before the trees were in

full leaf, and the church disappeared

back into its secretive copse. In the

graveyard you'll find Edward Falconer,

who died while Vicar of Old Newton in

1946, at the age of 98 years. He had been

Vicar here for more than half a century,

and his headstone tells you that he was known

as Britain's oldest working clergyman.

|

The

nave and chancel are mismatched in a pretty way,

the chancel high-ridged and red, the nave

flatter, simpler, without aisles or clerestories.

The chancel is pleasingly rough and ready, with

brickwork and wooden-traceried windows. The tower

is not big, but seems imposing against such a

simple building. You step through the rustic

south porch into a nave which seems wider than it

is, thanks to the low roof, with the beams proud

of the white ceiling. There's a nice west

gallery, screened off beneath, and the battered

15th Century font stands in front of it. In the gallery, the seating

is organised for children, boys on one side and

girls on the other. There are also places for

Master and Mistress.

Looking

east, everything is simple and seemly. There was

a staunchly Anglican restoration here in the 19th

Century, and this period created an impression of

substance and significance which chimes well with

the Decorated windows. Unusually, the location of a nave altar is revealed, not by a piscina, but by a surviving sedilia.

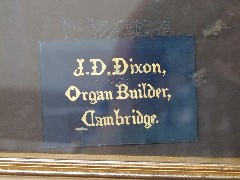

| Perhaps the most interesting

things here are idiosyncracies. The war

memorial is one of the strangest I've

ever seen, cut as fretwork in the style

of an indian temple, or perhaps the

Brighton Pavilion. The organ, up in the

chancel, is a fine modern one, but the

makers plate and memorial plaque from the

old one are displayed beside it, along

with the paperwork, a satisfying

historical detail. There is some 15th

Century canopywork up in the top of a

nave window, as well as some fragmentary

beasts, who provide, just for a moment, a

reminder of what was once here. Arthur Mee, an

enthusiast if ever there was one, rather

damns Old Newton with faint praise.

Forced into a perusal of the registers to

find something interesting to say, he

homes in on John Mole, the son of a farm

labourer, who was baptised here in 1743.

He astonished his friends with his

marvellous calculating powers, and

went on to write two books about algebra.

Mee also tracks down John Bridges, who

was a vicar's son in the 19th century,

and is best remembered as one of the

leaders of the modern system of

philosophy called Positivism. What

induced such a tiny, rural parish to give

birth to two great thinkers? Something in

the water? A curiosity to ponder, in such

an utterly rural churchyard.

|

|

|

|

|

|