| |

|

|

|

|

riverrun, past Eve and

Adam's, from swerve of shore to bend of bay. Ours

was the marsh country, and from the strand I

climb to the marsh gate, and there across the

wide marshes stands All Saints. Here, thousands

every year see Ramsholt church for the first

time, and every time is like the first time. Now,

I step out across the marshes, and in my mind I

am Dickens's Pip, I am Joyce's Dedalus;

signatures of all things am I here to read.

A bright, freezing day in January 2017, and a

perfect day for cycling out to Ramsholt church. I

caught the Lowestoft-bound train to Melton, and

then cycled out along the long, rolling, busy

peninsula road, the traffic quietening as it

peeled off to larger, less remote places. The

fields flattened out, punctuated by wind-swept

pines. The lanes narrowed, zig-zagging down the

sides and along the ends of pre-enclosure strips.

A sea of mud and ice caked the road surface, and

soon almost every trace of human habitation had

disappeared. Curlews and oyster-catchers huddled

miserably in the open fields as I reached the end

of the long lane which leads up to Ramsholt

church. |

Hardly anyone lives in this parish,

but it still maintains a service a month as a result of

the Anglican diocese's benefice system. Although this

church is just about accessible by car, most people who

visit here will come on foot. This is because, just

beyond the lane that leads to the church, another lane

leads down to the pub on the quayside, the Ramsholt Arms.

Today, this pub is one of the busiest in Suffolk. It

hasn't always been so; When I moved to Suffolk thirty

years ago you could come here on a sunny day and enjoy

the silence of the shoreline as you sat behind your pint

of Adnams. It was considered by those who knew of it one

of the best kept secrets in the county. A peaceful,

laid-back pub overlooking the wide river - what more

could you want? The food was superb, and you could be

assured of the friendliest of welcomes.

And then came the 1990s, and Suffolk was 'discovered'. It

is hard to remember now just how unfashionable it had

been before. As recently as 1986, Michael Palin could

make a comedy film, East of Ipswich, about going

on holiday with his parents in the years after the War to

Southwold. Southwold! How absurd! Who would ever want to

visit such a backwater, let alone go on holiday there!

Nowadays, it is hard to pick up a colour supplement

without finding an article about some actor, or designer,

or investment banker who has a holiday cottage near the

mouth of the Deben or the Blyth. Foodie articles focus on

Suffolk produce and Suffolk restaurants. House prices

have rocketed; it simply isn't possible for young locals

to live here any more. A beach hut recently exchanged

hands in Southwold for about the same as my house in the

middle of Ipswich is worth.

And places like Ramsholt are becoming overwhelmed. From

being a quiet haven where you took your mum for lunch

when she visited, the Ramsholt Arms has become a tourist

pub, its large garden full on a summer's afternoon with

yachting types up from London for the weekend. Does this

sound snobbish? I'm sorry. But you might as well be in

Southwold or Aldeburgh.

A large field has been converted to a tourist car park

about half a mile before you reach the pub. You walk down

onto the strand; although we are a good three miles from

the sea, the beach is sandy, and children dig holes and

build castles. The lazy river is shallow and slow, if a

touch muddy, and paddling is certainly safer than it

would be a couple of miles downstream at Bawdsey. The

tide is dramatic; at the turn, it retreats a hundred

yards out in less than twenty minutes, leaving a vast

expanse of shiny mudflats, an aerodrome for the seagulls.

You wander along the strand upstream, taking care not to

step on the samphire that grows there. You step up onto

the level above, and through a gate onto the bridleway

through the marshes. And you see the church for the first

time.

From across the reeds, it rises dramatically above you.

The round tower appears square at this distance, but as

you come closer it begins to look oval, an illusion

caused by the buttressing. A similar illusion occurs at

Beyton, Suffolk's other buttressed round tower.

The bridleway winds leisurely across the flat marsh. But

it is best to keep to it; deep channels snake among the

reeds and gorse, and only the brown cattle that somehow

find something to graze here seem sure of not falling

into them.

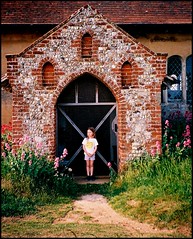

If you have come here in

spring, you are in for an absolute delight when

you pass through the gate on the far side of the

marsh. Here, a sunken lane winds up to the

church. Until fifty or so years ago, these were

so common, but most were either turned into

roads, or allowed to return to nature. This one

is lined by high banks, six feet or more, and

they are a riot in spring of wild flowers and

grasses. Poppies spangle them into the distance.

The lane climbs, and suddenly you reach the

churchyard. It is about eight feet above you, and

you can either continue up to the field and

around to the north east, or there is a little

stairway cut in the bank of the sunken lane. This

takes you up into the graveyard itself. |

|

|

It would be silly to call this a

lonely place, because it has thousands of visitors every

year, and unless you come in deepest winter as I did on

this occasion, you cannot be here for long without

someone else turning up. But it is lonely in the sense

that it is virtually all there is under the sky, apart

from an impossibly pretty thatched farmhouse down in the

dip beneath the church. The river stretches beyond the

marshes (you can just make out the spire of Felixstowe St

John on the horizon, some six miles away) and the air is

empty except for plaintive bird cries and the wind in the

reeds. On a hot, still day, even these are silenced, and

you'll swear you can hear the distant clink of boat masts

in the river, half a mile off.

This is an ancient place. There was a church here a

thousand years ago, and perhaps the base of the tower

survives from that time. The church is broadly Norman;

the later medieval windows can't disguise this. North and

south are strange sets of dumpy lancets, which could date

from any time, I suppose. They allow you to see how thick

the walls are.

However ancient All Saints is, the strongest resonances

here are of the 18th century. This seems to be the last

time the Parish was populated to any extent, and there

are some superb 18th century headstones set in the wild

grasses, including one with a sexton's tools. My four

favourites are in a line, to the Waller family. The

Wallers can still be found locally; they owned the living

at nearby Waldringfield and presented their sons to the

living. The last Waller rector of Waldringfield died in

harness as recently as 2013.

The location and pre-Tractarian

character of the graveyard and church meant it provided a

perfect setting for a recent BBC adaptation of Charles

Dickens's Great Expectations (although the book

is actually set in the north Kent marshes, of course).

Curiously, there are hardly any stones to the north of

the church. This may be used as evidence for the myth

that people are never buried on the north side of

churches (in practice, they are - take a look at a few

churchyards!) but I think it is simply that people here

have chosen to be buried looking over the river - well,

you would, wouldn't you.

As you step through the 19th century porch (the frontage

is most unusual; bricks lining unknapped flintwork, like

a seaside cottage) and into the open church (it is always

open) you might be forgiven for thinking that the

interior is also an 18th century survival. There are

simple wooden box pews, a brick floor, a two-decker

pulpit rising on the south side. It is all just about

perfect.

In fact, all of this is the result of a restoration of

the 1850s. In the first half of the 19th century,

Ramsholt church was derelict; unused and unloved. The

nave was open to the sky; the walls were 'green with

damp'. It seems extraordinary that a church would be

furnished in the prayerbook fashion at such a late date,

although it probably reflects the predilections, and

memories, of elderly churchwardens. Ramsholt is such a

backwater that this was still thought to be the proper

manner of furnishing a church. As you walk up to the

altar, you'll notice that the seats face west, towards

the pulpit, rather than east, towards the altar, a

reminder that for 300 years it was the Word that was the

focus of Anglican worship, not the Sacrament.

There's a nice late

medieval font, which seems rather out of place

here; you feel that a chunky Norman font, or one

of those 18th century bird baths as at

neighbouring Bawdsey, would be more appropriate.

The simple Norman doorway into the tower seems to

call out for the former. If you look through the

cracks in the door, you'll see that the base of

the tower has been furnished as a vestry.

The damp of the estuary inevitably creeps into

this building still, but that is part of its

charm. On a summer's day it is cooler inside than

out, as if the church were holding on to the grip

of winter. On a winter's day the church becomes a

sanctuary, but in all seasons a serious house

on serious earth... the ghostly silt

not yet dispersed. There is something organic

about this great oatmeal tower, and the way it

and the sandy bluff merge into the reeds and

pines above the Deben estuary, at one with its

setting, its parish and its long generations.

And that is all there is to Ramsholt now. The

pub, a farmhouse and the church, each about half

a mile apart. And the marshes, and the water, and

the wide Suffolk sky. |

|

|

|

|

|

|