| |

|

|

|

It was

May 2001, and I was cycling out across

the gently rolling acres of north

Suffolk. Redgrave is one

of those large and relatively

self-sufficient villages that you get

more in the north and west of Suffolk

than around Ipswich. However, this was

not apparent to me, as I approached it

from the direction of Wortham Common. I had

cycled through the Long Green, a strange,

otherworldly place. The Commons and

Greens around here were still, until half

a century ago, intensively grazed. Now,

they have been let go back to nature, and

are in many places covered in gorse and

furze, with outcroppings of angular

trees. Occasionally, as at Wortham, there are

settlements which seem carved out of the

common land. There’s nowhere else in

Suffolk quite like it. I left this behind, and a

deep cutting of a lane led me up and out

into open fields. The sun came out, and

the tower of St Mary was ahead of me. It

is a curious sight. Suffolk has a handful

of towers rebuilt in the 18th century.

Mostly, they are red brick, as at Layham, and rather less

successfully Grundisburgh. However,

Redgrave’s tower is white brick, and

would be quite at home in the City of

London, if a little more austere than

most there.

|

Attached

to it is a huge church. St Mary is big;

it is a little-known church, but has more to

offer than most. Simon Jenkins ignored it in England’s

Thousand Best Churches; most probably, he

didn’t know about it. It would fit quite

comfortably into his three star category along

with the likes of Westhall which he also missed.

Incidentally, when I met him and pointed out his

omission of Redgrave and Westhall, he looked at

me as if I was some kind of sad lunatic. I

suppose that he’s approached by someone with

a similar complaint at least twice a day.

I stepped inside to a vast space.

This church is full of light. The clerestory and

aisle windows are huge, and although the east

window is full of coloured glass, it too is vast,

one of the widest I've seen. It would take

hundreds and hundreds of people to fill this

place, more than a thousand perhaps; but it was a

gentle reminder to me that our medieval parish

churches were not built for congregational

Anglican worship.

St Mary has one of Suffolk's three

best brasses, the 1609 memorial to Anne Butts. It

has been reset in the sanctuary floor. She was

related to the Bacons, that mighty Suffolk

family, and her inscription reads:

The weaker sexes strongest

precedent

Lies here belowe; seaven fayer years she spent

In wedlock sage; and since that merry age

Sixty one years she lived a widowe sage

Humble as great as full of Grace as elde,

A second Anna had she but beheld

Christ in His flesh who now she glorious sees

Below that first in time, not in degrees.

Mortlock thought it the finest

post-Reformation brass in England.

To get to it, you will have to pass

an awesome table tomb in the north aisle. On it

lie, life-size, Sir Nicholas and Lady Anne Bacon.

Lady Anne was the daughter of Anne Butts (and Sir

Nicholas her son-in-law) so we may assume that

they are responsible for the quality of her

memorial. But the grandeur of theirs quite

outshines her, and everybody else. It is by

Nicholas Stone, famous for the Coke memorial at Bramfield; she died in 1616, he in

1624. There is an excellent modern window behind

it.

The Bacons are responsible for most

of the thirteen hatchments here - more than in

any other church in Suffolk. Others are for the

Holt and Wilson families (who later

intermarried). The latest is dated 1929. One of

the Holts can also be found up in the sanctuary.

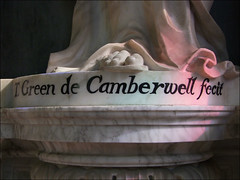

In a remarkably grand memorial by Thomas Green of

Camberwell. He's life-size, as you might expect

here. Sir John Holt was Lord Chief Justice of

England and died in 1709. He sits in his judge's

robes, and he's flanked by the two voluptuous

figures of Justice and Mercy.

In this great palace of slightly

absurd grandeur, mention should also be made of

the vast wooden decalogue hanging in the north

aisle. I've never seen Moses and Aaron look so

important. It once stood at the east end of the

chancel, has ridiculously large scrolls, and

would certainly have concentrated the mind. All

of this is overseen by that lovely glass in the

huge east window. Mortlock tells us it is by a

local firm, Farrow and son of Diss. I thought it

splendid, quite in keeping with this mighty

place. Also in keeping is the white stone pulpit,

which is rather camp, although one assumes this

was not the intended effect.

In 2004,

three years after my first visit to Redgrave

church, the parish walked away from it. The cost

and effort of maintaining this vast barn full of

priceless treasures had become too great a burden

for the small congregation, so they locked the

doors and decamped to the village hall, declaring

that St Mary was now no longer their

responsibility. As you may imagine, this caused a

certain amount of consternation. While Redgrave

church is a building of national significance,

there is a certain protocol required if you want

to declare a building redundant and have it

conveyed into the stewardship of the Churches

Conservation Trust. Not being able to pay the

repair bills is not considered a good enough

reason to declare redundancy. Even so, the parish

persisted, which rather placed the Diocese in a

quandary. While their first responsibility was to

the parishioners, they clearly did not have the

resources needed to look after St Mary, and yet

the church commissioners would have looked with

some doubt on any attempt to declare the building

redundant.

It was, in

modern political parlance, uncharted territory.

Nevertheless, it was obvious that the ultimate

destination must be to ensure the future security

and upkeep of the building, and so after eighteen

months or so of what one imagines must have been

fairly tense meetings, the church was conveyed

into the care of the Churches Conservation Trust.

And in the

meantime, something else had happened. The shock

of the incident had galvanised some local people,

including a few of the former congregation, to

get together and form a group to look after St

Mary. With the support of the Churches

Conservation Trust this has become one of the

most successful support groups in the county,

putting on exhibitions and concerts for which the

church is eminently suitable. Before the end of

the decade, the Daily Telegraph

newspaper awarded Redgrave church the prize of

English Village Church of the Year. On that

occasion I was asked by BBC Radio Suffolk to do

an interview about the church while standing in

the nave, and as I looked around I thought it

seemed a happy ending.

In fact,

within a few months I was back at Redgrave church

for a quite exciting reason. The Eastern Daily

Press of 13th July 2010 takes up the story: It

had remained hidden for centuries. But the

entrance to a 500-year-old vault beneath a

medieval Suffolk church has been discovered after

a woman accidentally stamped her foot through one

of the floor tiles. While rehearsing a scene from

an upcoming performance of the musical Quasimodo

at St Mary's Church, in Redgrave, near Diss,

actor Kathy Mills dislodged a marble flagstone

near the altar and her foot disappeared into a

dark void below. Mrs Mills, who is in her 60s,

suffered a swollen ankle, but the pain soon

subsided when she was later told she had

uncovered a tomb never seen in living memory with

coffins inside suspected to contain the remains

of the village's past aristocracy.

Just weeks before a geophysicist had used an

advanced radar to map out where the

long-forgotten vault was, but if it was not for

Mrs Mills' freak accident they would never have

been certain of where its boarded-up entrance was

or what hid inside. The church is now hosting an

open weekend to give the public a chance to

glimpse through the hole and see exactly what

they've been walking above all these years. St

Mary's Church will be open to the public this

Saturday and Sunday, between 10am and 4pm, where

a video camera will beam images from inside the

vault onto a projector screen.

“I was just doing a rehearsal for the

production and I walked onto the flagstone,

whether it was already loose I'm not sure, but my

foot went down,” said Mrs Mills. “They

lifted it up (the flagstone) and you could just

see some mud and sand underneath. It's possible

my foot went down eight inches. I wondered where

I was going. It was quite a shock. I was thrilled

when they told me I had discovered this vault

they did not know was there. One or two people

call me the Tomb Raider.”

Rumours had circulated for decades that under the

ancient slabs of the 14th century church, now

owned by The Churches Conservation Trust, laid a

labyrinth of passages and tombs. Bob Hayward,

chairman of the Redgrave Church Heritage Trust,

said stories had passed through the generations

of how people walked through the tunnels as

recently as the 1920s, but records of their

existence cannot be found. In a bid to establish

fact from fiction, the group employed Malcolm

Weale, of Geofizz Ltd, from East Harling, near

Thetford, about two months ago to analyse what

lied below. Using a ground penetrating radar, Mr

Weale identified a large void, about 6ft deep,

spreading under the altar and into the adjacent

vestry. The Trust was prepared to leave its

investigations at that until the day of Mrs

Mills' fateful accident just over a week ago.

When the damaged flagstones were lifted and a

light was lowered down, a tunnel was discovered

with a set of steps descending into the ground

visible in one direction and a cluster of about

six coffins tucked inside a dark chamber in the

other. It appears timbers holding up the floor

tiles had rotted. Mr Hayward said: “It's

exciting. You think you know these places but you

don't until something like this happens.”

It is thought the coffins belong to descendents

of the Holt family. Sir John Holt became lord of

the manor in 1703 and a large memorial to his

life sits above the newly uncovered vault.

However it is believed to have been built in the

late 1500s by the Bacon family, but their remains

are located in another tomb beneath the church's

font. Archaeologists will be descending into the

vault at the end of the year to assess whether

any of the other supporting timbers are rotten

and to record what's inside, but the coffins will

remain as they are found.

Now, this

was something I had to see. The hole was about

20cm by 40cm. Bob Hayward very kindly opened it

up the hole for me and allowed me to lower my

camera into it - it wasn't safe to go down there,

because of the high concentration of carbon

monoxide.

How exciting!

My photograph showed the high-vaulted tunnel of

18th Century brick, and in a room beyond there

were five lead coffins, almost directly under the

magnificent Holt memorial.

| This was

a fascinating experience, and all in all

St Mary is a fascinating church, one of

the best in East Anglia, despite what

that Jenkins book says. It is not

understated, it never attempts to be

tasteful or refined. After the thrill of

exploring the tunnel, I sat for a moment

on the steps leading up to the organ at

the west end, surveying the wonderful

brick floors, the expanses of light

beneath the arcades, the awesome

seriousness of the chancel. If, at that

moment, a group of 18th century ladies

and gentlemen had stepped out of a Samuel

Richardson novel and into this church, I

should not have been the least bit

surprised. And curiously, Redgrave

village is not the largest population

centre in the parish. That honour goes to

Botesdale, down on the main

road, and part of the extended village of

the Rickinghalls. Botesdale has its own church, but strictly

speaking it is a chapel of ease to this

one. The most famous residents of the

parish these days are not Bacons, Holts

or Wilsons, but the extremely rare great

raft spiders which live in Lopham fen, to

the north of the village. It is one of

only two places they are found in the

British Isles.

|

|

|

|

|

|