| |

|

| |

|

Visiting St

Catherine always brings back resonant memories

for me. Looking back at my notes, I see that one

of my visits was on the Easter Monday of 2009.

The busy rituals of the last few days now over,

it should have been time to relax in the

sunshine, but for the first time in nearly a

week, the sky was overcast with thick grey cloud

which glowered at the land beneath. It was a day

which would have suited Good Friday rather

better. And yet, I always feel energised by the

events of Holy Week. The daily going-to-church

puts me in touch with the experience of my

medieval ancestors, and it is rather

awe-inspiring to take part in the the liturgies

which they knew at this season. It reinforces my

sense of medieval churches as a touchstone, and I

was glad to be cycling out in the lonely parishes

around Stowmarket, even if I might have hoped for

some sunshine.

In fact, the weather on that day had rather

suited St Catherine, and I also remember the

first entry for this church on my Suffolk

Churches website back in October 2001. I had

observed then that late autumn was a good time to

visit St Catherine. And now it was 2018, and late

autumn again.

The church sits beside a wood, on a hill above

the narrow road. It sounds idyllic, but this is

agricultural country. There is a hardstanding

area for vehicles below the rise of the ploughed

field, and the containers parked on it on this

muddy day made it bleak. I thought then, and

think now, that this was not a bad thing, and as

I pushed my bike up the steep swampy track I

could easily imagine Victorian funeral

processions making the same journey.

The tower of St Catherine is certainly quite

something. It is that unusual thing for Suffolk,

a square Norman tower, with very little

alteration since. Looking back at the south side

of the church, you can see the roof beams

protruding, tied and braced to the outside of the

wall with huge wooden pegs. Generally, the

exterior of the church has been patched up rather

than rebuilt, with massive brick buttresses on

the north side, although there was a proper

restoration here by diocesan architect Richard

Phipson, the porch a typical one from his Boys'

Bumper Book of Genuine Medieval Features (1878

edition).

Phipson was a conscientious architect, and his

work has a degree of comforting self-confidence.

And there is something stern and glowering beyond

to contrast the church with, a high perimeter

fence at the top of the opposite rise. We'll come

back to it in a moment.

St Catherine is kept open all the time as, I

suppose, all parish churches should be. I always

look forward to coming back, because, in my

opinion, St Catherine is pretty much what a

remote village church should be. It is clearly

ancient, but entirely refurbished inside. There

are no major monuments or significant medieval

liturgical survivals, but it is open.

Not for tourists then, but as a church open for

prayer, or even just for the special silence of

an ancient place. It is dim inside without being

gloomy, and a bit damp, making an organic

transition between graveyard and church. You can

sit here awhile, and know you are in the presence

of God. I like that a lot.

The village of Ringshall is a surprisingly large

and suburban place, but a mile or two distant

from here. You'd never know it was nearby, not

least because of the way the corrugating ridges

around here cluster and conspire to hide the

landscape.

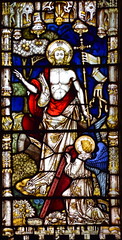

As with virtually all parish churches, money was

lavished here in the late 19th Century, and a lot

of it was spent on stained glass. The glass is

early work by Clayton & Bell, dating from the

time of Phipson's restoration. It is clustered in

the chancel around the sanctuary. The best of it

is in the east window, depicting the Resurrection

of Christ and Mary Magdalene meeting the Risen

Christ in the garden. Less good are the familiar

pairing of the Good Shepherd and Light of the

World in the south side of the chancel. Clayton

& Bell would not often return to these

particular subjects. But they remain as a lovely

and valuable statement of what seemed important

to a remote East Anglian parish in the 1870s.

There is one of those 13th century Purbeck marble

fonts more familar from the east of Suffolk,

supported here on pretty Victorian pillars.

Everything else, pretty much, is Phipson's,

although the rough-hewn roof beams look ancient

and must have been reused. They look low enough

for you to hit your head on.

Unusually, there is what appears to be a piscina

set in the east wall of the sanctuary, behind the

altar. Phipson was far too liturgically literate

to reset one there, and it doesn't appear to be

an aumbry in disguise. Why it is here and not in

the south wall as usual is a mystery.

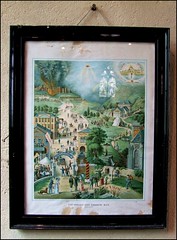

Up in the sanctuary hangs the standard of 74(F)

Squadron Royal Air Force. It was put here in

1992, to remain until it turns to dust. An

unusual survival is a real period piece hanging

up at the back of the church. It is a picture

called The Wide and Narrow Paths, and it

was the sort of thing produced by evangelical

church societies in the late 19th Century,

intended for hanging up in a house rather than a

church. It depicts all the stumbling blocks on

our journey through life. Verses from the Bible

are used to illustrate where we can fall. As far

as I could make out, it looks like we are all

going to hell.

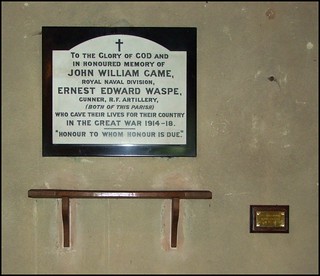

Back in 2001, I had come here a week or so after

the invasion of Afghanistan by American and

British forces, in the wake of the destruction of

the World Trade Centre. Now, I stepped outside

into the graveyard, where the day was still

deciding whether or not to bother me with rain.

The graveyard is wide and open, the long grass

climbing the slope. I walked up to the top of it,

and found that the extension eastwards consisted

almost entirely of military graves.

Looking westwards, there was that perimeter fence

again. St Catherine is one of three medieval

churches on the edge of the Wattisham airfield,

one of the country's major military helicopter

bases. At the time of my first visit, many of the

people here were involved in the assault on

Afghanistan. The thought of this was quite a

contrast with my feelings about the inside of the

church.

The other two medieval churches beside the base

are at Great Bricett, near the main gate, and the

village of Wattisham itself, where the church is

now redundant. Of the three, St Catherine is most

obviously the one that serves the local military

community. The ancient ways that once linked

these three communities have now disappeared

beneath the towers, hangers and runways of the

western military-industrial complex.

I wandered back down the slope of the graveyard,

and as I did so a huge pheasant exploded from

behind a headstone. It fled into the woods,

whirring like a helicopter. As I watched it go, I

saw what I should have noticed before. There were

about a dozen of them, perched silently in

attitudes of stupidity and defiance, on stumps

and branches, watching me warily. Their sullen

splashes of red were an empty threat in the

darkening day. |

|

|

Simon Knott, November 2018

Amazon commission helps cover the running

costs of this site

|

|

|