| |

|

|

|

In the summer of

2016 I decided to try and revisit all the

East Anglian churches I'd not been to

since buying my first digital camera back

in 2003, and Shadingfield was high on my

list. I took the train up to Brampton

station. Brampton is a request stop on

the rambling East Suffolk Line which, in

no particular hurry, joins Ipswich to

Lowestoft through a succession of small

east Suffolk market towns. I think it is

safe to say that Brampton is the most

remote stop on the line, two miles from

the village whose name it takes, and with

just a couple of houses for company. It

is actually much closer to the village of

Redisham, but I'm told that the

Victorians named their stations after the

nearest post office. I was once told by

one of the cheery ticket clerks at

Ipswich station that I was the only

person to whom he'd ever sold a ticket to

Brampton. If you decide to go there

yourself, make sure you don't

accidentally buy a ticket to Brampton in

Cumbria by mistake. Shadingfield is also a

couple of miles from Brampton station,

and it is one of those quiet little

places you often find lost in the lanes

of north-east Suffolk. The energetic

antiquarian David Elisha Davey was a

regular visitor in the 1820s and 1830s,

always spelling it 'Shaddingfield' in his

journals, which remains the modern

pronunciation. The population of the

parish reached a peak of 220 in the 1851

census, of whom almost a half were

attending the church on a Sunday, a

spectacularly high proportion for east

Suffolk.

|

St John the Baptist stands

above the road between Beccles and the A12. The

tower is 15th century, later patched in red-brick

on the north and west sides, which lends it an

endearingly homely quality. Below it on the south

side of the nave is one of those pretty red-brick

porches you frequently find in Suffolk. A Tudor

design of this kind is usually thought of as

being early 16th century, but the image niche is

surprisingly small, and may not even be for

images, and so I wondered if the structure might

actually post-date the Reformation. It conceals

an attractive late 12th Century doorway.

The font stands on a high

platform in the shape of a Maltese cross as at

nearby Weston and, further afield, at Laxfield.

I'm told that baptising babies in these fonts can

be a precipitous affair. The font itself is late

medieval, its panels with shields in quatrefoils

seeming to match those on the base, suggesting

that they were made for each other. The little

heads that peep out from the corners are

delightful. It is probably earlier than the

Weston and Laxfield platforms, both of which

support seven sacrament fonts, so it may have

provided a model for them.

As with many churches in

north-east Suffolk, the unaisled nave and chancel

here run into each other with nothing to mark

their division - or, at least, almost nothing.

For here, although the roodscreen has long gone,

there are two extraordinary corbels set in the

north and south walls, that once supported the

roodloft. The one to the south is formed of a

head, that on the north side of a pair of heads

pressed together, apparently showing us that two

heads are better than one.

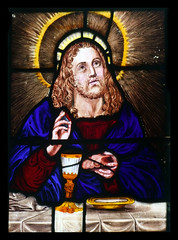

The east window contains panels of English and

continental glass. The roundels of the Adoration

of the Shepherds and the very faded Ascension are

both Flemish, I think, but the panel of Christ

blessing bread and wine, probably from an Emmaus

scene, is likely to be English, perhaps by a

local workshop of the early 19th Century. In the

north wall, there is a lancet containing unusual

and beautiful enamelled glass, a memorial to Mary

Kilner who died in 1858, a delicious High

Victorian moment.

There are

fragments of a surviving wall painting

scheme in the nave. That on the north

wall appears to be a Passion sequence -

you can still make out the panel of

Christ being whipped. Elsewhere in the

nave, there's a good set of Charles I

royal arms, and that curiosity of this

part of the county, a banner stave

locker. There are twelve churches in the

Lowestoft area that have them, and their

use appears to be for containing the

wooden poles used to carry images and

crucifixes in medieval processions. Fair

enough - but why only around here? Did

other medieval churches possess wooden

cupboards? So why have none survived?

Perhaps its just a Lowestoft area thing,

the need to tidy bits away.

This parish is famous for the

Shadingfield altar cloth, a rare and

unusual lace-trimmed textile that was

given to the church in 1632. This was at

the time when Archbishop Laud was trying

to reintroduce sacramental practices back

into the Church of England, including the

re-establishment of altars in chancels.

The move fell to the fury of the

puritans; Laud was executed, the altars

were removed, and the pulpit became the

main focus of Anglican worship for the

next 200 years. The altar cloth itself is

now on view in Strangers' Hall Museum in

Norwich. |

|

|

|

|

|