| |

|

Like many medieval

churches in Suffolk, St John the Baptist is

remote from the village it serves. Or, it would

be more accurate to say that the village is

remote from the church, since the church stands

on the main road from the A12 to Aldeburgh, and

the village is off this road, a mile or so to the

south. The position of the church probably

reflects the fact that it is high, firm ground,

while the village is in the marshes.

This is not to say that the village is not a busy

place too of course, for just across the River

Alde, and actually in Tunstall parish, are the

world famous Snape Maltings, once the dockside

and railhead of the Garrett industrial empire,

and now home to the Aldeburgh Festival.

Ironically, the tourists that flock the craft

shops, galleries and cafes of the Arts Centre,

and go for walks along the reed-banked creeks and

across the marshes, probably don't often make it

up to the busy top road and the church.

The building today looks pretty much like

Ladbroke's 1820 drawing. The Victorians didn't do

much here, there was no building of aisles,

transepts or trimmings. The only real change is

the eastern wall, rebuilt in 1920 to replace the

heavily buttressed yet collapsing original. This

is a simple, aisleless church, with no

clerestory. The roofline on the tower shows that

it was once thatched. It is, let us say, a

typical country church. The tower was built as

the result of a bequest in the middle years of

the 15th century, and the battlements added

later, in the style of the 1520s. The porch is

contemporary with the tower. The nave and chancel

are earlier, probably 13th century, and although

they have been patched up over the years, there

has been no wholesale rebuilding.

Inside, however, the modern age has been busy.

You step into an utterly charming interior, full

of light, with white walls and brick floors. At

the cleared west end is the church's great

treasure, one of the most beautiful fonts in the

county. It bears a dedicatory inscription to the

Mey family, and dates from the late 15th century.

Strange animals lurk around the foot of it, and

tthe stem bears the Evangelists with their

symbols, interspersed with kings. But the most

animated figures are those on the bowl. Seven of

them hold a long scroll that goes right around

the bowl. The eighth panel is a rare

representation of the Holy Trinity, which was

particularly circumscribed by iconoclasts in the

16th and 17th centuries. It shows God the Father

seated on his throne, with the crucified Son held

in front of him. The Spirit descends in the form

of a dove. On either side kneel the donors of the

font.

David Davy, visiting in the

1830s, said that the whitewash had been recently

removed from the font. Perhaps what he meant was

that the figures had been covered in plaster,

which would explain their survival. Certainly,

the puritan iconoclast William Dowsing saw

nothing to incur his displeasure when he came

here in 1644, and almost certainly the Anglican

reformers had plastered it over a century

earlier, the usual way of dealing with the

problem of removing images while not actually

destroying the font, which was still required by

the new religion.

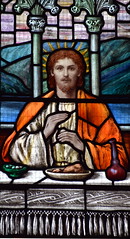

The views to east and west are beautiful, the

colour of the Arts and Crafts east window

perfectly poised and balanced. In the top half,

Christ breaks bread at supper at Emmaus. Below,

two angels flank the River Alde at Snape Bridge.

It dates from the 1920 restoration, and is by

Mary Lowndes, perhaps the leading female artist

in any medium of the last years of the 19th and

first years of the 20th centuries. She is best

known today for her work for the suffragette

movement - she designed their posters. Through

her work at the Glass House she was an influence

on many younger artists, both male and female.

Below it, there is often

set a beautiful altar frontal, illustrating a

line from Eliot's Four Quartets. The

church used to have a 15th century brass of five

little girls. Davy made a rubbing of it, which is

in the British Museum, but the brass has been

stolen or mislaid since, probably in the 1920

wholesale refurbishment of the chancel.

Outside in the graveyard, the war memorial is one

of the most extraordinary in Suffolk, a

broken-down classical feature looking down the

road to the village. Unfortunately, it is not a

pleasant walk because of the traffic, but there

are a couple of good pubs, and the walks across

the marshes beyond the Maltings are certainly

worth the effort. Not far off is Snape Mill,

bought by the young Lowestoft-born Benjamin

Britten as a place to write, and to which he

returned from America at the height of the War.

He had read an article about George Crabbe's poem

The Village with its account of the

fisherman Peter Grimes, and knew that back home

in Suffolk was where he had to be, and an opera

based on the poem was what he had to write.

|

|

|