| |

|

| |

|

If you

were asked to name 400 of Suffolk's

500-odd parishes, there's a fair chance

you wouldn't think of Stanstead. The

village is a quiet backwater, straddling

the main road on the outskirts of larger Glemsford,

but the church of St James is on the hill

above, looking out over the valley. You

can't help wondering how many people

looking for Stansted airport, twenty five

miles off in north Essex, absent-mindedly

type this spelling into their GPS and are

surprised to end up in the middle of

nowhere. I'd last been here

about ten years previously, and it was a

delight to roll up on a sunny morning in

April 2013 and to find St James in such

fine fettle, the churchyard full of

primroses and celandines, the church open

and welcoming. A few years previously I'd been told by a

usually reliable source that this church

was threatened with closure by the rather

eccentric Rector whose benefice covered

the parish at the time. He felt that not

enough people were coming to hear him

preach. The irony is, of course, that St

James is still open to pilgrims and

strangers everyday, but that minister's

main church across the valley in the

largest village in the benefice was, and

is, kept locked. And St James is the

lovelier church, I think. Cautley treated Stanstead

with considerable disdain during his

great survey of the 1930s, but the High

Victorian character that he so abhored

has matured, and here at St James is to

be found in full flower.

|

With

a sweet irony it is the priest's door in the

chancel which is kept open. It is directly into

the chancel that you step, so you might not

notice the original 14th century south door, with

all its fittings. It's worth a look. Internally,

the chancel is of good, honest rural 19th century

quality, from the sequence of tiles in the

sanctuary, which are surely an indication of the

hand of diocesan architect Richard Phipson, to the memorials to

Rectors Samuel Sheen pere et fils - this

is grand Victorian Gothic writ homely.

The tower makes the church

appear larger than it is; inside, it is

tiny. On the north wall is a good set of

Queen Anne arms, probably the single most

interesting pre-Victorian survival here.

Either side are two windows, one with

some surviving medieval glass in the

tracery, the other with excellent 19th

century glass, thoroughly in the spirit

of its medieval predecessors. It even

recreates the familiar sense of an

amalgamation of medieval glass collected

from elsewhere - but it isn't. I wonder

who it was by.

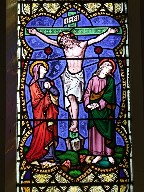

Finally, the glass in the

east window. As far as I'm aware, this

artist has also not been identified, but

it is a good complement to the tilework

of the sanctuary, a serious crucifixion

of the 1870s perhaps.

|

|

|

|

|

|