| |

|

|

|

Stradbroke

is perhaps the least well-known of

Suffolk's small towns. But it has a busy,

independent air, with its shops, school,

library and leisure centre. It reminds me

of places of a similar size in France.

The church is in the centre of town, a

large, imposing building. The 15th

century tower, with its raised stair

turret, is visible from miles away.

Niches flank the west window, other

windows build via a bell window to high

battlements. It is one of Suffolk's

biggest towers, probably because this was

the parish of the De La Poles, now

sleeping peacefully at Wingfield. Simon Cotton

found a bequest for a new bell in 1428,

which usually followed hot on the heels

of a new tower, so is probably a good

date. All Saints is open every

day, and you get the impression that

people wandering around are just as

likely to be locals availing themselves

of a spot of spiritual refreshment as

visiting pilgrims and strangers, which is

nice. It is a most welcoming interior.

|

The vicar in the

second half of the 19th century was the

formidable J.C. Ryle, the famous protestant

evangelical. He had an enthusiasm for plastering

any available space with quotations from the

Bible. His are the near- Soviet era banner

slogans at Helmingham, designed to keep any

Tractarian tendency of the Tollemaches in its

place. Here, his work is rather more subtle and

aesthetically quiet, on the chancel arch and

roofbeams. They were painted as part of a major

restoration of the 1870s. The architect was R.M.

Phipson,

fresh from his complete rebuilding of Ipswich St Mary le Tower; this church is on a

similar scale, although the exterior is pretty

much intact, apart from a thorough refurbishment.

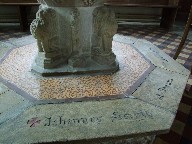

Below the tower,

there is a dramatic picture of the interior

during this restoration, a reminder of just how

drastic some of these makeovers were. Ryle and

Phipson reduced All Saints to a gaping shell.

Consequently, not much survives of the medieval

liturgical integrity, except the font, which was considerably

recut but still retains its dedicatory

inscription,

and an amazing niche in the sanctuary. Mortlock feels it was

probably an Easter

sepulchre,

but I don't see why it can't just have been a

niche.

Another medieval

survival is a pair of rood screen panels in the

chancel. They may not have come from this church

originally: they depict two Old Testament Kings,

of whom Ryle would approved, and may have been

purchased and installed here as part of the

restoration. They are, not inappropriately, very

heavily restored themselves. The Clayton &

Bell glass in the east window was installed at

Ryle's behest, depicting a pulpit and a lectern

alongside a font as a reminder to the Stradbroke

faithful that the Word was at least as important

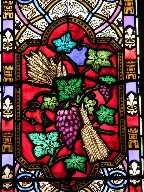

as the sacraments, if not more so. The glass at

the west end is better, I think, including a

memorial window to Queen Victoria and some

beautiful depictions of roses, lilies, wheat and

grapes by the O'Connor Brothers beneath the

tower.

Other points of

interest include a large number of ledger stones

at the west end of the nave. One is to two

parents, who both died at the age of 25, leaving

two infants too young to be sensible of their

loss. The altar frontal and hangings in the

south aisle chapel, beautiful designs of wild

flowers apparently worked by a one-armed curate,

are a delightful contrast with the stern

puritanism of J.C. Ryle's chancel. Stradbroke is one of a

handful of churches in East Anglia to have a

royal arms to the current monarch.

| Stradbroke's

most famous son was the ruthless

opportunist Robert Grosseteste, Bishop of

Lincoln in the 13th century. He was

lionised after the Reformation for,

supposedly, standing up to the Pope; in

fact, he aligned his diocese with the

Barons rather than the King, and thus

creamed off money that would have gone to

Rome via the Crown. He became fabulously

rich, as did his crony Simon De Montford,

who led the landed nobles against Henry

III in the Barons' War. Barmy old Arthur

Mee, in his The King's England, treats

Grosseteste as some sort of all-round

Great Englishman and proto-Protestant

hero. The church that Grosseteste

knew, and was baptised in, was not this

one, but was probably on the same site.

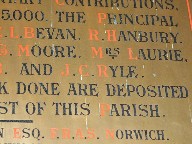

In the 1880s, J. C. Ryle left here to

become first Anglican Bishop of

Liverpool, but the mark of his Muscular

sleeves-rolled-up Christianity survives

here. Also does his name on a brass

plaque beneath the tower, noting him as

one of the benefactors of the

restoration.

|

|

|

|

|

|