| |

|

|

|

The Ipswich to

Manningtree road cuts off a long tongue

of land from the rest of Suffolk. As the

great Rivers Orwell and Stour roll

towards the sea, the edge inexorably

closer to each other, until at Shotley

gate they meet before emptying into the

North Sea. This huge natural harbour is

now home to England's largest container

port, but you wouldn't think anything of

the kind could be so close in the gentle

woods and lanes of the Peninsula, except

for the cranes which occasionally peep

above the treetops, of course. The

setting of St Peter is idyllic: you head

down through Holbrook, and then into the

woods. It sits in a close with several

awesomely grand houses for company, and

the Stour estuary is below, wild Essex

beyond.

The appearance of the church is a little

unusual, and requires some

interpretation. This is one of the south

towers found commonly in the Ipswich

area. No south aisle was ever built

beside it as at neighbouring Holbrook,

but several successive Victorian

restorations saw the addition of a long

south transept which contains an organ

chamber and a vestry which is largely

invisible from inside the church, and the

rebuilding of the chancel with the

addition of a north aisle and transept.

But the original tracery of the chancel

east window was moved into the chancel

aisle, which explains why such an

overwhelmingly 19th century extension has

a medieval window. |

None of the restorations

were the work of a major local architect. There

seems to have been a rolling programme of

refurbishment throughout the 1840s and 1850s,

probably at the behest of a Tractarian-minded

Rector. The two major restorations came in the

1860s and 1870s, and although Richard Phipson, as

Norwich Diocesan Architect, certainly oversaw the

work, the combination of, first, Hawkins of

London, and then the firm of Francis, has left

something unusual and interesting.

Stepping inside, this is an almost-entirely early

Victorian interior of some high quality. The

furnishings are the work of the great Ipswich

woodcarver Henry Ringham, who, despite going

bankrupt after overspending on his infamous

Gothic House, was still sufficiently highly

thought of some decades after his death to have

an Ipswich road named after him. If they really

date from 1842 then they are the major example of

his early work.

An outstanding feature of the west end is

Stutton's millennium window. These were installed

in many churches at the turn of the century, and

are too often kitschy and dull. No such charge

could possibly levelled against Stutton's. The

window is absolutely outstanding of its kind, at

once enthralling, theologically articulate and

inclusive. The artist was Thomas Denny, whose

work is more familiar in the west of England. The

upper part depicts a passage from Isaiah: And

a man shall be as an hiding place from the wind

and a covert from the tempest; as rovers of water

in a dry place, as the shadow of a great rock in

a weary land. And the eyes of them that see shall

not be dim and the ears of them that hear shall

hearken. The lower part depicts the

counterpoint passage from the book of Revelation:

And he shewed me a pure river of water of

life, clear as crystal, proceeding out of the

throne of the Lamb. In the midst of the street of

it, and on either side of the river, was there

the tree of life, which bare twelve manner of

fruits, and yielded her fruit every month: and

the leaves of the tree were for the healing of

the nations.

Either side of the west end

are memorials to 17th century Jermys. These are

rather striking - they were moved here at the

time the chancel was rebuilt, and depict Sir

Isaac and Lady Jane Jermy on the south wall, with

their son Sir John and Lady Mary Jermy opposite.

The verses are well worth a second glance for an

insight into 17th Century eloquence.

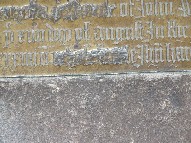

A remarkable memorial from more than a century

earlier is at first sight rather unexciting. It

is under the carpet at the east end of the nave,

commemorating John Smythe of Stutton Hall, who

died in 1534. It is a brass plaque in English,

reading O(f your charity pray for the soule)

of John Smythe, Knight. John deceased the XIIIIth

day of August in the year of Our Lord

MCCCCCXXXIIII O(n his soul)e Jesus have mercy.

There is no figure, no heraldic devices, no

trimmings at all. So what makes it so

interesting? Well, at some stage, probably in the

late 1540s, possibly in the early 1640s, or

perhaps at some time between or shortly

afterwards, all the parts of the inscription that

reflect Catholic theology and doctrine have been

viciously raked out, with either a sword-tip or

chisel. So, we have lost f your charity pray

for the soul and, at the end, n his soul.

A fascinating document of the protestant

intolerance of early modern England.

The chancel has been

reordered in a curious manner. The rood screen is

almost certainly also by Henry Ringham, making it

a work of some significance, and was installed

here before the chancel arch was rebuilt in 1862.

It has been set further east, with the altar

brought forward, and now provides an elegant

backdrop to the sanctuary.

All the 19th Century glass

is worth a look, being a record of work through

the decades of the 19th century. Some is the

1840s work of Charles Clutterbuck, which as

Pevsner points out makes them rare survivals in

Suffolk. As often on the peninsula, the church

suffered blast damage during the last War and

several windows are lost, but these losses are

recorded in their replacements.

The Ward &

Hughes-style window of St Helen and St

Peter appears to date from the 1850s, and

if so it is a remarkably early example of

such a thing in Suffolk, where such

papistry would have been controversial

until well into the 1860s. Powell's glass

of the post-Resurrection Christ greeting

his Disciples on the shores of Galilee of

a couple of decades later must have

struck a chord of familiarity in this

coastal parish, and remains a good

example of the workshop's early work in

Suffolk.

There is more good work in the north

transept and chapel, but unfortunately

this is now used as a meeting room, and

is kept locked. You can see it through

the glass partition, but it is impossible

to photograph. Otherwise, this is a

interesting and welcoming church, with a

beautiful setting and a strong sense of

continuity. |

|

|

|

|

|