| |

|

|

|

I have visited

several thousand country churches over

the last twenty years or so, and few

experiences are more haunting than to tip

up at some remote place and discover that

it was at one time one of the stars of

the Anglo-catholic firmament. Most

likely, it has long-since been subsumed

into the Church of England mainstream,

but that is not always the case.

Whatever, the evidence inside speaks of a

place which was once on the highest rung

of Anglo-catholic tradition, and Swilland

was such a place.

I remember, after I moved to Suffolk

thirty years ago, spotting St Mary across

the fields. My mind couldn't make sense

of what I was seeing. What was it? Some

strange Victorian folly? A water tower,

perhaps? It looks like nothing so much as

if a giant hand had picked up a Tudor

cottage, and threaded it delicately over

a lantern spire and onto the stump of the

tower. |

The hand, in fact, was that

of John Corder, an Ipswich architect remembered

by Corder Road in the town, where several houses

echo this Brothers Grimm fairy tale gothick. He

also rebuilt the church at Hepworth, although he

seems to have kept his imagination under wraps

there. Pevsner, in a rare moment when his sense

of humour shows through, described it as French

in character and vaguely of c.1500 in its motifs.

Sam Mortlock quite liked it, and called it

'beguiling'. He went as far as to describe the

lantern spire as 'perky'.

The village runs into the larger village of

Witnesham, which is outer-Ipswich suburbia

really, but Swilland still retains a sense of its

rural identity, and a feel of being a place where

ordinary people live quiet lives. There is an

excellent pub, the Moon and Mushroom. The name

Swilland means 'a place where pigs are kept',

although for miles around it is now barley which

sprawls across acre after acre. The main street

through Swilland is one of my regular ways back

into Ipswich from cycle rides, and so I see this

church often.

You enter the porch and

come to face with quite the most spectacular

Norman doorway in the Ipswich area. I think it

must have been recut a bit, but it reminds us

that this church was already old before the 15th

century tower and bell were installed, and that

it was ancient before John Corder came along.

The surprise comes as you step inside, for the

interior of this little church is redolent of

that gorgeous late 19th and early 20th century

Anglo-Catholicism, and while this may no longer

be the tradition at Swilland, it has left enough

of itself to show what it was once like. Your

eyes are drawn eastwards to a tall, gilt reredos

much in the style of Ninian Comper's at

Wymondham, the gilt Saints filling niches either

side of a crucifixion scene. I wonder who

designed it?

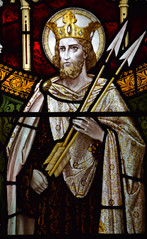

East Anglia's two great

Saints, St Felix and St Edmund, standin lights on

the south side of the nave with a brass

inscription to James Park Nelson and Philip

Bicknell bolted beneath them. Father Nelson and

Father Bicknell were the two priests who

established the Anglo-catholic tradition here at

Swilland and both are buried in the churchyard.

You can see their headstones below, Bicknell's a

grand, flowery cross, but Nelson's has succumbed

to the wear of time.

Back inside the church,

Nelson and Bicknell's memorial brass grows into a

Saxon cross inscribed with the words Jesu

Miserere, and the window was set by their

successor, Father Richard Faulconer. A third

figure to the west of the entrance shows St

Richard of Chichester and remembers Faulconer. He

had been ordained by Edward King, founder of the

Anglo-Catholic Keble College in Oxford and later,

as Bishop of Lincoln, champion of the

Anglo-Catholic cause in both his writings and in

the courts, which was often necessary in those

days of fierce resistance to anything considered

'Romish'. In tribute, the figures of St Felix and

St Richard, both of them Bishops, have been given

Edward King's kindly face.

The 15th

century font is painted in a 15th century style,

presumably also in the 1880s - you wouldn't have

got away with that in the 20th Century.

Curiously, directly opposite the window

remembering Father Nelson and Father Bicknell is

a memorial to a minister of some twenty years

earlier. Richard John Allen appears to have died

in harness in 1867, when Tractarian attitudes,

and what it must be said was a snobbish attitude

to the the literalism and triviality of Biblical

fundamentalism, were already firmly entrenched in

the Church of England.

But Allen's

memorial is surmounted by an open book

with the words ye must be born again,

a typically hardline response to

Tractarian ideas about sacramental grace.

Beneath we are told that he Faithfully

Preached the Glorious Gospel of the Grace

of God. And this just twenty years

before Faulconer's call for Jesu

Miserere - it must have been quite a

rollercoaster ride in this quiet little

parish in those days when either party

could accuse the other pharisaism, and

frequently did.

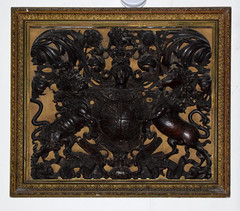

And yet, the Anglo-catholic party won in

the short and medium term, and in the

long term altered the face of the Church

of England. For it had something that the

biblical fundamentalists could not

compete with - beauty. Evidence of this

is a remarkable survival in the form of

the processional banner worked by Father

Faulconer himself, in velvet and gold

thread, studded with coloured beads. It

shows a crowned rose as an emblem of the

Blessed Virgin Mary. Near to it on on the

north wall is one of the best carved sets

of royal arms in Suffolk. It is that rare

thing, a set for Queen Anne. |

|

|

|

|

|