| |

|

I wonder how many times I

have visited this church's more famous neighbour

at Thornham Parva since last coming here? And

yet, I have always thought of it fondly. I

remember my first visit here in the 1990s, being

surprised and pleased to see a sign down at the

roadside telling me that the church was open. At

the time, I had visited several hundred Suffolk

churches, and although I had found most of them

open, this was the first time I'd come across a

church openly advertising the fact. Nowadays,

such signs are commonplace, but coming back here

in September 2018 I was happy to note that

Thornham Magna still has its sign out by the

road.

St Mary Magdalene's open welcome, and its high

quality 19th Century restoration, are perhaps

both symptoms of the philanthropy and generosity

of the Henniker family, of nearby Thornham Hall.

This is the Henniker church. If you walk

westwards of the tower, you will see Thornham

Hall over the fence, across a field. You will

also find yourself standing among the Henniker

graves, which are as understated and restrained

as the Hall itself.

Anyone who knows this part of Suffolk will surely

love it, a landscape of wooded lanes and gently

rolling fields. And the church gets a good number

of visitors, for the popular Thornham Walks wind

in the woods beyond the church, and there is a

good pub down in the village.

The church is attractively set above the lane on

a cushion of green and brown, although the 14th

century tower is rather forbidding, not least

because of the flat effect of the east wall

caused by the buttresses being flush with it.

There is something similar at Rendlesham. The

late medieval porch is elaborate, with three

niches which would have contained a rood group

before the Anglican reformers removed them only a

few decades later in the middle of the 16th

Century. Incidentally, the odd way in which the

porch abuts the window to the east of it might

suggest that a rebuilding was planned, but the

Reformation intervened.

You enter what is inevitably a rather dark

church, narrow and aisleless, the few windows

filled with a range of coloured glass. The gloved

hand of lukewarm ritualism fell heavily here in

the 19th century thanks to the Henniker family

wealth, and consequently not much that is

medieval survived. This church has none of the

rustic medieval charm of its neighbour at

Thornham Parva.

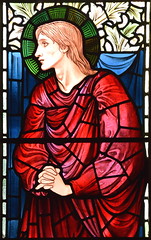

But in any case you come here for the Victorian

era, to see how a landed country family in that

period of renewed confidence and triumphalism

took its parish church to task and remembered

itself in death, for the Hennikers have their

memorials here, and what a contrast they are to

the triumphalism of the Tollemaches at Helmingham

or the Poleys at Boxted. here, there is a feeling

of understatement. The most memorable and

striking on a first visit is probably that to

Edward Henniker, who died in 1902. This is the

window in the south-west corner of the nave, with

figures by Edward Burne-Jones reused by Morris

& Co a few years after the artist's death. A

gorgeous St Mary Magdalene, a mournful St John

and the rather sombre Blessed Virgin stand as

they would have done at the foot of the cross.

The big restoration had

happened here in the 1850s, rather early for

Suffolk and consequently the patron and his

workmen had a fairly free hand. The elegant,

well-proportioned screen, in a typically bubbly

late medieval East Anglian style, was made by the

Ipswich carver Henry Ringham for a church in

Surrey. It was exhibited in the Great Exhibition

of 1851, but never seems to have been installed

in Surrey. The Hennikers bought it in 1856 and

had it installed here, where it looks very well.

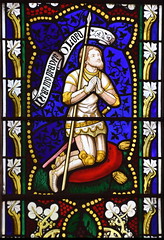

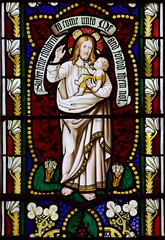

The glass on the north side of the nave by

William Miller was installed through the 1850s in

memory of members of the Henniker family.

Inscriptions were carved into the sill below each

window, but a rather unfortunate error in the

date of one (the inscription below the central

light of the middle window has the infant John

Chandos Henniker Major being born in 1844 and

dying in 1842) meant that the inscriptions were

soon covered by painted plate metal replacements.

Today, these lie on the sill below the original

inscriptions, so you can see both. The

unfortunate child, who had actually been born in

1841, is shown in the light above being held in

the arms of Christ. In the left hand light, his

father Major Henniker kneels in 14th Century

uniform holding a spear. He died at Pau in the

Pyrenees a few months after the death of his son.

The mawkish scene on the

other side of the nave, depicting the three women

at the tomb of Christ, is typical work of the

1880s by WG Taylor, but the other glass up in the

chancel is also by William Miller, also of the

1850s. Up here in the sanctuary is the Hennikers'

one attempt at full-blown triumphalism, the

memorial to John Henniker Major. It is by Joseph

Kendrick. Faith clasps the urn looking downcast,

a swan or cormorant peeping from behind her,

while Hope looks up, resting against her anchor,

a characterful face at once sorrowful and

earnest.

The Henniker memorials are an interesting history

of the colonial adventures of an established

landed family. One was killed in Spain, in

the Battle of Almanza, while another served

in the Egyptian Campaign... and throughout the

South African War. The memorial to the Major

Henniker commemorated in the window is by William

Woodington, who, Sam Mortlock reminds us, was

also responsible for the bronze reliefs around

the base of Nelson's Column. There are seven

Henniker hatchments, an unusually large number

even for Suffolk, which has more than any other

county apart from Kent.

But my favourite memorial of all, I think, is the

simple one to Martha Catherine Henniker, who was

born in July 1838 and died just three months

later. The tender plant shed forth its

beauteous form, look'd round upon this boisterous

world, found its chilling blasts too rough,

droop'd its head and died. Isn't that

lovely? I wonder if it can have been a comfort.

It is signed CRH, perhaps her mother or father.

Leaving, you can't help thinking that perhaps the

grieving figures in the Burne-Jones window

reflect something of this sadness in Martha

Catherine Henniker's inscription.

|

|

|