| |

|

|

|

Remote churches have a

peculiar fascination for me. It is as if they are

cut off in time as well as space. Things have

happened at a different pace, in different ways.

Sometimes, it seems as though they have been

forgotten, and that much has survived. In Suffolk

there are some lovely, unspoiled, remote

churches. I think of Badley, I think of Little

Wenham. But most of all I think of Wantisden.

It had been nearly twenty years since I'd last

visited Wantisden church. And yet, I had thought

of it often, and even passed it close enough to

see it off in the distance. The church is located

in fields about half a mile from the nearest

road. This is not that unusual in East Anglia,

probably a dozen others are equally remote. And

St John the Baptist has always been remote, for

there has never been a village of Wantisden. This

church served the residents of Wantisden Hall,

and their workers. |

What makes the church remarkable

however, is not its remoteness, but its location. Until

the 1930s, there were just two little cottages about 400

yards north of the church, by a bend in the little river.

They were called Bent Waters cottages. At the start of

the second world war, this whole area was requisitioned

by the military, and by 1950, USAAF Bentwaters was one of

the biggest and busiest military airbases in the world.

The site of the cottages is somewhere under the main

runway now, the river long-culverted. The church was

enclosed by the military area until the 1950s, when the

new perimeter fence cut in and put it outside the base.

However, the only access to it was through the base (the

fields were still cordoned off as tank training areas) so

anyone who wanted to tend a grave had to have a military

escort through the base. At this time, the modern top

road didn't exist, and the nearest other road to the

church was a mile away. When the fields were reopened in

the sixties, the current top road was built, and a

footpath was put in from it. In the 1980s, it was turned

into a roadway, but it was still shown on OS maps as a

footpath, perhaps because of its proximity to the

airbase. It seems that Russia wasn't the only country

during the cold war to put deliberate errors on maps to

confuse the enemy.

St John the Baptist is a Norman church, with a 15th

century Coralline Crag tower, one of only two in England.

The other is about a mile off at Chillesford, where you

can also see the medieval quarry from which the crag was

dug. Simon Cotton tells me that bequests were made for

this tower in 1445 and 1449. A derelict stable,

presumably for the rector's horse, sits on the southern

perimeter of the churchyard. Given the location of St

John the Baptist, you might think that the church has

been declared redundant, but it is still looked after as

part of the Orford benefice, a tremendous act of faith

and love.

You collect the key from the Hall Farm office at the top

of the track (of interest to fans of the BBC TV show

The Detectorists, for this is the depot where Lance

works in all three series) and step in through the small

Norman south doorway of the church into an organic space,

close to the earth from which it springs, rough and ready

and yet also lovingly kept. Above the doorway is a

grinning grotesque headstone, probably a lion, an early

medieval symbol of Christ. Turning east, the chancel arch

is Norman, a rare beast in Suffolk. Above it, the 18th

Century decalogue boards are in their original place, and

a royal arms dated 1800 hangs on the north wall.

The bench ends are medieval, their

figures entirely destroyed, although enough remains of

one to show that it may well have depicted a fox

preaching to geese. They probably came from elsewhere,

but some crude 17th Century benches huddle in the north

west corner, and this was no doubt their original home.

The font is a great round tub of a thing, contemporary

with the chancel arch. It is one of England's few

surviving Norman fonts built of blocks of stone. Wall

paintings on the south nave wall are indistinct, though

you can still make out a consecration cross. The rood

loft stairs still turn up from the south-east corner of

the nave, whilst up in the chancel the wooden credence

shelf survives in the 14th Century piscina.

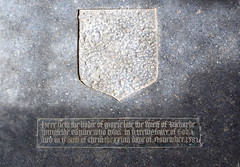

Ann Comyn, on the north chancel wall, exchanged time

for eternity in 1832. Mortlock observed that such a

transition seems unremarkable in a place like Wantisden.

Before that, Mary Wingfield lyved in ye trewe feare

of God and died in the faith of Christ in 1582.

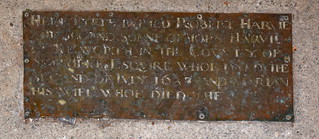

Robert Harvie, one of the Harveys of Ickworth, was having

no such truck with even such puritan sentiments as these

when he died shortly before the start of the English

Civil War in 1637, his inscription simply telling us that

he died and was buried. Curiously, the inscription also

records the death of his wife Marian, who died the

- but there the inscription ends. Presumably it was

installed before her death in full expectation that she

would join him, but perhaps in the tumult and fury of the

Civil War and subsequent Commonwealth she moved

elsewhere, or was even forgotten.

Outside in early spring, the wind

ruffles the bare trees, and the churchyard begins to

overgrow the mainly 19th Century graves. There is the

Tunstall forest in the distance, dark and forbidding. But

the most surreal view is to the west. Here, 20 metres or

so from the tower, is the perimeter fence of the USAF

base, abandoned in the early 1990s. When I last came here

in 2000 the buildings were boarded up, the control tower

had the cladding hanging off it, the runway, as wide as

Heathrow's, was overgrown, and sheep grazed all around.

Beyond were the nuclear missile bunkers, built to be

indestructible. All this has now been replaced by mundane

warehousing and storage facilities, poor neighbours to

the thousand-year-old church.

I thought back to my first visit here in the early 1990s,

watching from beneath as an F1-11 jet screamed into the

sky. It was from this base that the Americans bombed

Libya in 1987. And that same decade, while the brave

women of Greenham Common were protesting about Cruise

Missiles there (how long ago that now seems!) the US

Airforce was quietly stockpiling nuclear warheads here.

At one time, USAF Bentwaters is said to have stocked

enough nuclear weapons to destroy the world 5 times over.

And accidents do happen. In a

forgotten leaflet in the depths of Suffolk Libraries'

reserve collection, I found a story that, in the 1940s,

there was an accident at the nearby tank school. Several

people were killed, and the cracks in the walls of

Wantisden church are still there. But, this church

survives, thanks to the loving care of the local faith

community.

This is a strange place,

like no other. It stands as a witness to a

millennium of faith. The vivid sandy colour of

the coralline tower, full of fossilised shells,

rears primevally above the corrugated fields.

When I came here in 2000, a couple of elderly

parishioners were planting a millennium yew tree

in the churchyard, grown from a cutting of a tree

believed to be already a thousand years old, as

old as this church.

Time passes. And there is still a great sense of

permanence here, because the evidence is so close

at hand that, as empires rise and crumble, as the

violence of the 20th century sinks back into the

silence of these ancient fields, as the years

turn into millennia, faith endures. And so, of

course, does love. |

|

|

Simon

Knott, April 2018

|

|

|