| |

|

|

|

Rickinghall

Inferior, and its neighbour Rickinghall Superior, are names that seem to

have stepped straight out of the pages of

a Thomas Hardy novel. The names mean

'Lower' and 'Upper', of course, not a

distinction which needs to be reached for

in many East Anglian villages. The Rickinghall Superior church is up on the hill

beyond the bypass, mean, moody and

redundant. The Inferior one is down in

the centre of this trim, slightly

suburban village, which stretches for a

couple of miles along the A143, becoming

Botesdale and the parish of Redgrave

before you realise it. Rickinghall Inferior church

is strikingly pretty, like a pretty girl

whose eye you catch in the street; lush

and ornate, it almost seems to flutter

its eyelashes. Partly, this is because of

the delicious topping out of the Norman

tower, turned into a Decorated wedding

cake in the early 14th century. The

strong aisle and long porch accentuate a

sense of voluptuousness, with their

ornate decoration, some of it Victorian.

The gorgeous porch, with its elegantly

arcaded and seated open windows, is the

icing on the cake.

|

Stepping

inside, I was instantly reminded of the interior

of the church at Thelnetham, a couple

of miles off. From the outside, the commonality

is not so obvious, because Thelnetham has a

square tower, but the interior is strikingly

similar, with a wide south aisle, as wide as the

nave, and an ornate piscina set in the south-east

corner of the aisle. Both churches have a most

unusual feature, carved tracery in the east

windows, and it seems reasonable to assume that

the naves, aisles and chancels of both churches

were built by the same masons to the same design,

at roughly the same time, against existing

towers.

Unfortunately, Rickinghall Inferior drew the

short straw when the 19th Century restorations

were being handed out. While Thelnetham's came

under the reasonably safe and steady hand of

Diocesan Architect Richard Phipson, St Mary fell

under the heavy gaze of JC Wyatt, who

unfortunately rather anonymised the interior.

Everything is pretty, but heavily restored. The

reredos is made of medieval panels, but they are

too short to have been a roodscreen dado, and so

may well have originally fronted the rood loft.

They are painted in a medieval style, which is

interesting, and more successful than the fairly

dour 19th century Way of the Cross in the east

window above. More interesting, however, is the

question of where the panels went between the

destruction of the rood loft in the 1540s, and

the construction of the reredos more than 300

years later. Did Wyatt find the rood screen still

in place in the 1850s, or had the panels been

pressed into use for another purpose in the

meantime? Or did they come from another church

altogether?

| Another intriguing detail is

the font. As is familiar from the first

part of the 14th century, it has arcading

carved with window tracery, including an

exact copy of the chancel east window.

However, it was never finished. The

natural conclusion is that the work was

interupted by the Black Death, but it

does suggest that during this period the

fonts were bought uncarved by parishes,

and then the designs were added in situ. There

are a couple of nice panels of Flemish

glass, probably 18th Century, which

appear to depict the disciples at the

Last Supper. As in many Suffolk churches,

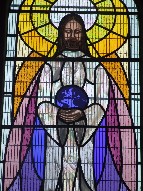

the millennium project here was a stained

glass window, an image of Christ the

Saviour of the World, placed in the east

window of the aisle, and signed Eckersley

in a snail. Having moaned about the glass

in the chancel east window, I was pleased

that this one was like a breath of fresh

air, but I can't honestly say that I

thought it was particularly exciting.

There does seem to have been a loss of

nerve in the design of stained glass in

recent years, perhaps the fault of those

commissioning it. Dramatic abstract forms

seem to have been replaced by

increasingly safe naive figurative art,

and although the window at Rickinghall

Inferior doesn't stoop to a secular

subject like some, it doesn't fire the

imagination as, for example, Surinder

Warboy's treatment of the same subject at

Chillesford

does. Still, local people that I spoke to

seemed to like it.

|

|

|

|

|

|