| |

|

|

|

There are several

missionaries noted for their work in

evangelising the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of

East Anglia, but the two most significant

are St Felix and St Botolph. Felix seems

to have been an extraordinary man. A

Burgundian, he was invited into the

Kingdom by the royal family. Establishing

his see of Dummoc in the ruined Roman

fort at Walton

Castle, just to the south

of the royal capital of Rendlesham, he

had, within a dozen years or so,

converted almost the whole of the vast

Kingdom to Christianity. But

it is one thing to raise fervor, quite

another to make it sustainable. Shortly

after, Botolph arrived from Germany, and

established a monastery at Icanho, on

that wild, mysterious point in the Alde

marshes at Iken.

Boston in Lincolnshire used to make a

claim to be Icanho, but in recent years

it appears to have learned that there is

more money to be made out of selling its

role in the foundation of the

Massachusetts city of Boston to visiting

Americans. Botolph set out across the

Kingdom establishing minsters where the

sacraments of Holy Mother Church could be

administered. Botolph's triumph was to

bolster the formation of a settled

clergy, and thus the formal structure of

the Catholic Church. This would capture

quite brilliantly the imagination of the

East Anglians, who in turn would help

form the Church's development for almost

a Millennium. Even after the formation of

a united England, East Anglia would

continue to be known across Europe as Our

Lady's Dowry.

|

Because

of the work he had undertaken to make Iken

habitable, Botolph had a reputation for warding

off evil spirits, which placed him in great

demand, particularly in ghost- and demon-ridden

Suffolk. Intriguingly, there are several parables

between the legend of St Botolph and the

Anglo-Saxon epic poem Beowulf. Recent

historical investigation and textual analysis

have led to an increasing academic consensus that

Beowulf is, in fact, an East Anglian

production. When Botolph died, his remains proved

equally efficacious in exorcising the

countryside, but they eventually found a

permanent home at Beodricsworth, the modern Bury

St Edmunds. Even after the establishment there of

the great shrine of St Edmund, the scale of

pilgrimages to the relics of St Botolph was

second only to that of visits to the corpse of

the young King himself.

I

get a huge number of e-mails from geneologists,

particularly in North America, who are confused

because they do not understand the difference

between villages and the parishes in which they

lie. Simply, all England is divided into

parishes; these originally defined the area over

which a local church would have jurisdiction.

Within these parishes, settlements grew up, the

largest of which ususually took on the name of

the parish, although this is not always the case.

Such a village is often at the centre of its

parish, and the medieval parish church is often

to be found there, but this is also not always

the case, and is often not so in East Anglia.

Some parishes were shaped by economic

developments long after the establishment of the

Parish system. In the north Suffolk parish of Redgrave, for

instance, increasing traffic on the road between

Bury and the coast, which ran through the south

of the parish, encouraged the monks of Bury, who

owned the land, to establish a fair in the 13th

century. A new settlement grew up, a mile or so

away from the village called Redgrave, but still

in the Redgrave parish. Honouring its second

favourite adopted son, Bury Abbey founded the

fair to be held in the week of St Botolph's Day.

The inhabitants of this new village applied for,

and received, permission to build a chapel of

ease to the parish church of St Mary, which was

way across the fields beyond Redgrave village.

Inevitably, the chapel was dedicated to St

Botolph, and the new settlement became known as

Botesdale - literally, St Botolph's Dale. It

grew, and joined onto the the neighbouring

village of Rickinghall, in a neighbouring parish,

to form a kind of north Suffolk super-village.

Today, Botesdale forms its own civil parish; but

even now, a thousand years on, it remains in the

Saxon-founded ecclesiastical parish of St Mary,

Redgrave.

The

chapel is set back from the road on a slight

rise, with a small grassed area in front.

Intriguingly, it is semi-detached from a

contemporary house on the west side. The

juxtaposition of flint and Suffolk pink wash is

an attractive one. The most interesting thing

about the church is an inscription above the

south doorway, a survival from a dramatic epoch

in English history. The Black Death, which

visited and revisited East Anglia in the middle

years of the 14th century, radically altered the

political and economic complexion of the country.

It also altered the priorities of the Church. The

rising Middle Classes, who had come to prominence

in the consequent boom years which were a legacy

of the Black Death, became obsessed with ensuring

a swift escape from purgatory after their own

deaths. The best way of making this happen was

that the living would say prayers for the souls

of the dead, and this was achieved by those rich

enough to do so by the foundation of chantries. A

chantry is a type of bequest, usually in the form

of land, the income from which was to pay for a

Priest in perpetuity, who would lead Masses and

devotions for the health of the soul of the dead

donor. That one was established here at Botesdale

is immediately apparent as you walk up the path,

because above the door, and still discernible

despite a later window having been cut through

it, you can read in Latin Pray for the Souls

of John Shrive and Juliana his wife. Pray for the

soul of Margaret Wykys. This was probably

set in place in the 1470s.

Unfortunately,

the very members of the Nouveau Riche

who made chantries popular would all too soon

embrace one of the radical ideas from the

continent which was a precursor of emergent

capitalism - in this case, Protestantism. The

protestant advisors to the young Edward VI would

energetically break the link with England's

Catholic past by outlawing chantries, and prayers

for the dead in general - ironically, a Priest

caught saying prayers for the dead could now be

put to death himself. And so, Anglicanism was

born. However, the new congregational liturgy

brilliantly devised by Thomas Cranmer had no need

for the multiplicity of vast churches which the

years of Catholic devotion and bequests had left

behind. Inevitably, the Botesdale chapel was sold

off, and for many years was home to Botesdale

Grammar School, founded in the 16th Century by

Sir Nicholas Bacon, who you can still see lying

in considerable splendour across the fields at St

Mary.

You

step into a church which is broadly late 19th

century in character. The school had seen its

best days by the time of the Restoration of the

Monarchy in the late 17th century, but soldiered

on in various guises as private anc commercial

schools until finally closing in 1878. The

building was sold off, the old chapel being

conveyed to a trust for use as an Anglican place

of worship. As this was still Redgrave parish,

and as Botesdale was still a thriving settlement,

the building once again assumed its role as a

Chapel of Ease, as it had been 350 years before.

| A lot of the woodwork came

from other churches, and thus predates

the 1880s. The chancel area is rather

curious, being a result of a 1980s

reordering. It must have seemed the very

thing at the time.The loveliest feature

of the interior is the west gallery, a

big one which houses the organ, and from

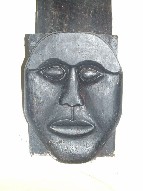

which you can see some primitive, carved

faces in the roof, which are presumably

17th century. Clearly, the gallery was

intended to enhance the capacity of the

interior, and because of this it lends

the western end of the building the air

of a non-conformist chapel, which is not

a bad thing. By

contrast, the east window glass by

Heaton, Butler and Bayne is spectacular

in such a setting. Curiously, the mother

church of St Mary at Redgrave was

declared redundant in 2003, and so today

this little chapel is the principal place

of worship in the parish, along with the

mission room at Redgave, recently

reinvented as All Saints.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|